If large companies were required to donate even a small proportion of their revenue to the alma mater of their chief executive, a handful of already elite universities around the world would find themselves a great deal richer.

This is one of the conclusions that can be drawn from the Times Higher Education Alma Mater Index (Global Executives) 2017, which ranks universities according to how many qualifications they have awarded to chief executives of members of Fortune magazine’s Fortune Global 500. This is a ranking of the world’s 500 largest companies by revenue, whose total earnings in 2015 were $27.6 trillion (£22.3 trillion). This is well in excess of the entire gross domestic product of the US, which was $18 trillion in 2015, according to the World Bank.

Indeed, that some chief executives have qualifications from more than one institution means that if the companies’ revenues are attributed to each university that has awarded their chief executives a degree, the combined total approaches $40 trillion. While the index uses a simple methodology and is limited by the public availability of information, it nevertheless provides an interesting snapshot of top chief executives’ academic background.

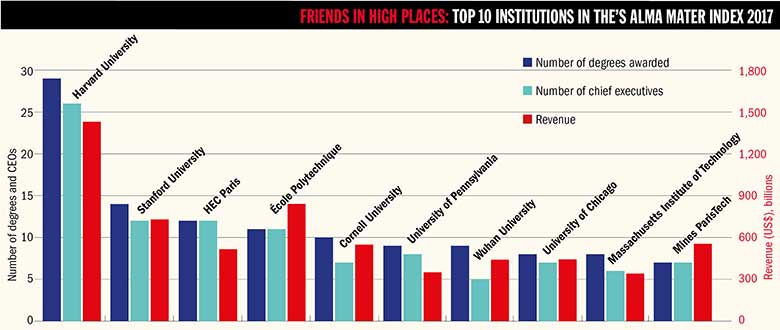

The university that had educated the greatest number of chief executives is Harvard University, which has conferred 29 qualifications (including undergraduate and master’s degrees, as well as doctorates and other postgraduate qualifications) on 26 chief executives of companies with a combined 2015 revenue of more than $1.4 trillion.

In second place in the index is Stanford University, with 14 degrees conferred on 12 chief executives of companies worth a combined $729 billion. Two French grandes écoles come next in the ranking: HEC Paris, a business school, and École Polytechnique, a technically focused institution. The latter institution educated 11 chief executives, but, together, their companies generated more than $840 billion in 2015: $100 billion more than those run by Stanford graduates.

The UK’s highest-represented institution is the University of Oxford. Its seven degrees conferred on six alumni overseeing companies generating some $280 billion place it 14th in the index.

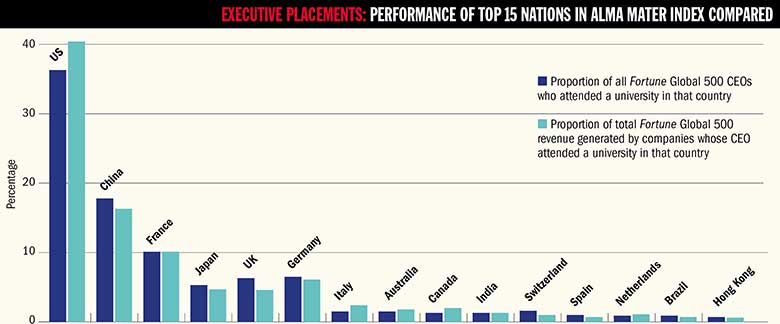

Overall, US institutions have educated 231 Fortune Global 500 chief executives: by far the highest number. The US is followed by China, whose universities have educated 116 chief executives; France, with 68; Germany, 46; the UK, 40; and Japan, 35.

But the extent to which those figures reflect the relative strength of those countries’ higher education systems, as opposed to their large populations and the number of large companies headquartered there, is very much open to debate. Those six countries also have the most companies in the Fortune Global 500, in almost the same order. In fact, examining the top 15 nations in the Alma Mater Index, the statistical correlation between the number of Fortune Global 500 chief executives their institutions have educated and number of Fortune Global 500 companies based there is 0.95, where 1 is a perfect correlation.

About two-thirds of Fortune Global 500 companies are run by chief executives who have a degree from the country where the company is based. When the analysis is confined to the top 100 companies, the correlation gets even stronger, with about three-quarters of chief executives holding domestic degrees. Of the 35 US companies in the top 100, 34 have chief executives with qualifications from US institutions. Only Dion Weisler, chief executive of the information technology company Hewlett-Packard, and Steven H. Collis, head of the drugs company AmerisourceBergen, have undergraduate degrees from universities overseas: Australia’s Monash University and the University of the Witwatersrand, respectively.

Andrea Masini, the associate dean in charge of the MBA programme at HEC Paris, believes that companies’ apparent preference for domestically educated chief executives is understandable because candidates for the top job “certainly have to understand the culture of the company”.

“It’s clear that a multinational organisation that has strong links to the country where [it] is established will tend to say: ‘Somebody from this country will understand the intricacies and nuances of the culture of this place and this country,’” he says.

HEC Paris educated the joint second highest number of chief executives in the index: 12, seven of whom run French firms. But does the high proportion of companies hiring from within their national talent pools mean that the much-touted international market for corporate leaders – often cited by apologists for those leaders’ multimillion-pound pay levels – is actually something of a myth?

Masini does not draw that conclusion. “I presume that every school has a particular level of visibility in the country where [it] is established, but I don’t think [French companies in the Fortune Global 500, such as] Total, Orange or AXA would take a French leader simply because that person is French [or has a French university degree],” he says.

Andrew Owens, co-founder and chief executive of Greenergy, a UK road fuel supply company that is 477th in the Fortune Global 500, agrees that companies do not deliberately favour candidates educated in their home countries. However, he believes that the alleged “huge internationalism” of corporate appointments is indeed “overstated”.

“If I am a multinational company operating in 100 countries, with a market capitalisation of £100 billion, I’m going to do a global search for a CEO. But if I’m a private company that has a value under £1 billion, I’m more likely to get a headhunter and find someone from down the road,” he says. “If you take a multinational that’s headquartered in the US… the most significant and financially oriented jobs are likely to be in the US. They’re likely to be applied for by US people, and therefore they’re likely to end up with a US [appointment]. It’s just maths. They might have an operation in South Africa or Singapore, but it’s not head office.”

Moreover, he notes, many companies appoint from within, and internal candidates, who began their careers at more junior levels, are particularly likely to have been educated in the company’s home country.

Owens, who is a chemical engineering graduate of Imperial College London, also notes that while having a degree from a world-leading university is no guarantee of stepping into a chief executive’s role, those with such qualifications are likely to be looked upon favourably given that one must be “very determined” to get into somewhere like Imperial or Harvard.

“You’ve got to want it; you’ve got to be talented,” he says. “But determination and talent are in your nature if you’ve got in. So you’re not going to suddenly leave there when you complete your course and wait for it all to come to you; you’re going to compete. Business is all about driven people…and it just so happens that clever, ambitious people are going to get into the top institutions. Why would you think that those same clever people won’t then be the more successful people in their next job?”

Jean-Michel Blanquer, former deputy director of the Cabinet for the French Ministry of National Education, Higher Education and Research, and dean of Essec Business School (88th in the Alma Mater Index, having educated two Fortune Global 500 chief executives), thinks that the prospect of generating future chief executives for their country’s largest firms is “very often a motivation” for governments when they consider how much to spend on higher education.

But he also believes in the international talent pool for corporate leaders. A good example, he says, is Carlos Ghosn (pictured inset), the chief executive of French car firm Renault, who is now running its Japanese rival Nissan. “Renault is now a global company, and Carlos Ghosn is, at the same time, from Lebanon, France and Brazil: he has different roots,” Blanquer says. “All the previous leaders [of Renault] were very French: it’s a good example of the willingness [of today’s multinationals] to have internationalised people.”

George Kohlrieser, professor of leadership and organisational behaviour at IMD Business School in Lausanne, Switzerland, and associate clinical professor of psychology at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, has been a high-level consultant to numerous Fortune Global 500 stalwarts, such as Accenture, Coca-Cola, Morgan Stanley and Nestlé. He believes that becoming top dog is “more performance-driven than it is education-driven”. But he does think it “very significant” that some global universities stand head and shoulders above the rest in the Alma Mater Index: of the nearly 400 higher education institutions that have awarded a degree to a Fortune Global 500 chief executive, only 63 have awarded more than two degrees. Stanford and Harvard, for instance, have educated 38 chief executives between them, and Kohlrieser thinks that this is partly connected to their academic standing: they are ranked third and sixth in the THE World University Rankings 2016-17, for instance. This “brand image” gives their graduates a certain aura, he says: “There’s something special about them if they made it into Harvard in the first place and were able to graduate…I think what you’ll find [within these people] is that drive to really learn, learn, learn, and be willing to do hard work to get where they’re at.”

He adds that the environment at top universities “does affect the mindset” of their students, who find that being surrounded by other “high performers really can be stimulating”. The mindset created by the necessity to “up their game” and to “be in there, trying to win” stimulates the “extra ambition that’s needed” to run top companies, Kohlrieser believes.

For Blanquer, the huge revenues associated with the world’s leading companies also underline a more general point about the central place that higher education plays in a country’s economic prosperity, given the ever-increasing need of such companies for highly educated talent, and their ability to relocate to the countries where that talent can best be sourced.

“Twenty years ago, you could say that the university was very important in society and you needed good universities to be a good country,” he says. “Today, [higher education] is much more than that: it’s the heart of the society and the economy. You are in or out in the globalisation [game] because of the quality of your HE sector. Research and higher education are as strategic as military and defence investment for a nation [if it wants to have] sovereignty in the world.”

Research by Tommaso Grant

Hothouse powers: The Times Higher Education Alma Mater Index 2017

| Rank in Alma Mater Index |

Position in the THE World University Rankings 2016-17 |

Institution | Country | Number of qualifications awarded to CEOs |

Number of CEOs educated |

Revenue ($bn) |

| 1 | 6 | Harvard University | United States | 29 | 26 | 1,429.62 |

| 2 | 3 | Stanford University | United States | 14 | 12 | 728.84 |

| 3 | NR | HEC Paris | France | 12 | 12 | 516.71 |

| 4 | 116 | École Polytechnique | France | 11 | 11 | 841.33 |

| 5 | 19 | Cornell University | United States | 10 | 7 | 547.56 |

| 6 | 13 | University of Pennsylvania | United States | 9 | 8 | 348.98 |

| 7 | 401-500 | Wuhan University | China | 9 | 5 | 439.78 |

| 8 | 10 | University of Chicago | United States | 8 | 7 | 444.13 |

| 9 | 5 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | United States | 8 | 6 | 340.23 |

| 10 | 251-300 | Mines ParisTech | France | 7 | 7 | 554.04 |

| 11 | NR | ENA, École Nationale d’Administration | France | 7 | 7 | 334.83 |

| 12 | 91 | Kyoto University | Japan | 7 | 7 | 231.89 |

| 13 | NR | Insead | France | 7 | 7 | 187.02 |

| 14 | 1 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom | 7 | 6 | 282.48 |

| 15 | 170 | University of Cologne | Germany | 6 | 6 | 336.76 |

| 16 | 39 | University of Tokyo | Japan | 6 | 6 | 275.33 |

| 17 | 201-250 | University of Stuttgart | Germany | 6 | 3 | 157.32 |

| 18 | 32 | New York University | United States | 5 | 5 | 415.64 |

| 19 | 20 | Northwestern University | United States | 5 | 5 | 208.24 |

| 20 | 4 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom | 5 | 5 | 184.41 |

| 21 | 72 | Seoul National University | South Korea | 5 | 4 | 145.54 |

| 22 | 112 | University of Göttingen | Germany | 5 | 3 | 176.8 |

| 23 | =36* | University of Illinois | United States | 4 | 4 | 359.83 |

| 24 | 16 | Columbia University | United States | 4 | 4 | 310.78 |

| 25 | 201-250 | Polytechnic University of Milan | Italy | 4 | 4 | 248.04 |

| 26 | NR | China Europe International Business School | China | 4 | 4 | 180.18 |

| 27 | NR | Shandong University | China | 4 | 4 | 161.76 |

| 28 | 601-800 | Tokyo University of Science | Japan | 4 | 4 | 141.89 |

| 29 | 8 | Imperial College London | United Kingdom | 4 | 4 | 135.78 |

| 30 | 35 | Tsinghua University | China | 4 | 4 | 129.02 |

| 31 | NR | Nankai University | China | 4 | 3 | 156.92 |

| 32 | 45* | University of Wisconsin | United States | 4 | 3 | 151.65 |

| 33 | 195 | National Taiwan University | Taiwan | 4 | 3 | 90.88 |

| 34 | 18 | Duke University | United States | 3 | 3 | 391.63 |

| 35 | 601-800 | China University of Petroleum (Beijing) | China | 3 | 3 | 367.07 |

| 36 | =80* | University of Pittsburgh | United States | 3 | 3 | 265.7 |

| 37 | 601-800 | Auburn University | United States | 3 | 3 | 256.39 |

| 38 | 60 | University of Southern California | United States | 3 | 3 | 246.6 |

| 39 | NR | Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications | China | 3 | 3 | 212.64 |

| 40 | 56* | University of North Carolina | United States | 3 | 3 | 187.39 |

| 41 | 30 | LMU Munich | Germany | 3 | 3 | 186.77 |

| 42 | 169* | Texas A&M University | United States | 3 | 3 | 179.33 |

| 43 | 33 | University of Melbourne | Australia | 3 | 3 | 173.01 |

| 44 | 351-400 | Hanyang University | South Korea | 3 | 3 | 169.72 |

| 45 | 14 | University of California, Los Angeles | United States | 3 | 3 | 168.53 |

| 46 | 7 | Princeton University | United States | 3 | 3 | 159.13 |

| 47 | 21* | University of Michigan | United States | 3 | 3 | 135.92 |

| 48 | 601-800 | Waseda University | Japan | 3 | 3 | 130.5 |

| 49 | 12 | Yale University | United States | 3 | 3 | 100.72 |

| 50 | NR | Sciences Po | France | 3 | 3 | 97.81 |

| 51 | 113 | University of Bonn | Germany | 3 | 3 | 78.15 |

| 52 | 78 | RWTH Aachen University | Germany | 3 | 3 | 75.35 |

| 53 | 601-800 | Keio University | Japan | 3 | 3 | 61.92 |

| 54 | 182 | University of the Witwatersrand | South Africa | 3 | 2 | 306.46 |

| 55 | 301-350 | University of Kent | United Kingdom | 3 | 2 | 135.48 |

| 56 | 251-300 | University of São Paulo | Brazil | 3 | 2 | 98.82 |

| 57 | 801+ | Southwest Jiaotong University | China | 3 | 2 | 95.65 |

| 58 | 501-600 | Harbin Institute of Technology | China | 3 | 2 | 94.68 |

| 59 | NR | Harbin Engineering University | China | 3 | 2 | 90.44 |

| 60 | 9 | ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich | Switzerland | 3 | 2 | 89.72 |

| 61 | 29 | Peking University | China | 3 | 2 | 70.74 |

| 61 | NR | Dongbei University of Finance and Economics | China | 3 | 2 | 70.74 |

| 63 | 82 | Technical University of Berlin | Germany | 3 | 2 | 58.07 |

| 64 | NR | Babson College | United States | 2 | 2 | 304.35 |

| 65 | 59 | Delft University of Technology | Netherlands | 2 | 2 | 296.18 |

| 66 | 51 | Brown University | United States | 2 | 2 | 195.59 |

| 67 | 401-500 | San Diego State University | United States | 2 | 2 | 179.31 |

| 68 | 141* | Rutgers University | United States | 2 | 2 | 172.81 |

| 69 | 501-600 | Xi’an Jiaotong University | China | 2 | 2 | 171.26 |

| 70 | 143 | University of Notre Dame | United States | 2 | 2 | 141.74 |

| 71 | NR | Hefei University of Technology | China | 2 | 2 | 137.55 |

| 72 | 351-400 | Iowa State University | United States | 2 | 2 | 130.64 |

| 73 | 10 | University of California, Berkeley | United States | 2 | 2 | 127.5 |

| 74 | 68 | Pennsylvania State University | United States | 2 | 2 | 117.65 |

| 75 | 351-400 | University of Houston | United States | 2 | 2 | 113.49 |

| 76 | 121 | University of Virginia | United States | 2 | 2 | 103.01 |

| 77 | 251-300 | Sapienza University of Rome | Italy | 2 | 2 | 102.81 |

| 78 | 601-800 | University of Science and Technology Beijing | China | 2 | 2 | 99.85 |

| 79 | 251-300 | Osaka University | Japan | 2 | 2 | 96.33 |

| 80 | 201-250 | CentraleSupélec | France | 2 | 2 | 95.48 |

| 81 | 70* | Purdue University | United States | 2 | 2 | 89.91 |

| 82 | 198 | Tilburg University | Netherlands | 2 | 2 | 87.53 |

| 83 | 401-500 | Huazhong University of Science and Technology | China | 2 | 2 | 86.64 |

| 84 | 501-600 | Complutense University of Madrid | Spain | 2 | 2 | 83.97 |

| 85 | NR | Bowdoin College | United States | 2 | 2 | 83.93 |

| 86 | 201-250 | University of Cincinnati | United States | 2 | 2 | 83.51 |

| 87 | 201-250 | Shanghai Jiao Tong University | China | 2 | 2 | 82.52 |

| 88 | NR | Essec Business School | France | 2 | 2 | 79.08 |

| 89 | 165 | University of Auckland | New Zealand | 2 | 2 | 71.86 |

| 90 | 201-250 | Boston College | United States | 2 | 2 | 70.4 |

| 91 | 401-500 | Lehigh University | United States | 2 | 2 | 70.05 |

| 92 | 42 | McGill University | Canada | 2 | 2 | 68.71 |

| 93 | 173 | University of Waterloo | Canada | 2 | 2 | 68.67 |

| 94 | NR | Pepperdine University | United States | 2 | 2 | 68.6 |

| 95 | 201-250 | University of Iowa | United States | 2 | 2 | 63.1 |

| 96 | 69 | Erasmus University Rotterdam | Netherlands | 2 | 2 | 55.76 |

| 97 | NR | Hitotsubashi University | Japan | 2 | 2 | 55.75 |

| 98 | 182 | Northeastern University | United States | 2 | 2 | 53.4 |

| 99 | 601-800 | Northwestern Polytechnical University | China | 2 | 2 | 52.07 |

| 100 | 201-250 | Korea University | South Korea | 2 | 2 | 49.56 |

NR = not ranked

The index methodology

Each chief executive’s education has been researched using biographies from sources such as company websites, press releases, industry association websites, conference speaker biographies and news sources. For a small number of individuals, Times Higher Education was unable to find details of their educational history.

Institutions in the Alma Mater Index 2017 have been ranked according to the total number of degrees awarded to chief executives. Where this was equal, they have been ranked according to their total number of chief executive alumni. Where this was equal, they have been separated according to the total revenue of their alumni chief executives’ companies in 2015.

The ranking is based on the chief executives listed by Fortune in the Fortune Global 500 2016.

If a company lists joint chief executives, we have attempted to include both alma maters where the information can be found, but revenue for the company is counted only once if the chief executives share an alma mater.

Where one chief executive is listed for two companies, the institutions are counted only once, but the revenue for both companies is counted.

Where a chief executive has two degrees from the same institution, the revenue is counted only once.

Where the degree-awarding institution has been subsumed into another institution or has changed name, the current name has been used.

Management schools have been listed under the parent institution.

Some short-course executive education management programmes have also been included. Except for the University of California, US multi-campus university systems are treated as one university. The listed position in the THE World University Rankings is that of the system’s highest-ranked campus and is indicated by an asterisk.

后记

Print headline: CEO academy