View the full results for the Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings 2017

The University of Tokyo has topped a new Times Higher Education ranking of the best universities in Japan, based on the teaching and learning environments that institutions offer students.

The country’s flagship research university takes the number one spot in the THE Japan University Rankings, which was produced in partnership with Japanese education company Benesse, while Tohoku University is second and Kyoto University is third.

The table, which includes almost 300 universities, was modelled on the inaugural Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education US College Rankings, which was published in September 2016.

Like the US rankings, the Japan list is based on four broad “pillars” (resources, engagement, outcomes and environment) that focus primarily on what the institutions offer students.

Overall, the country’s national universities are the top performers in the ranking. Of the 406 universities that THE calculated a ranking for, 73 are national universities, 89 per cent of which make the top 150. In comparison, only 22 per cent of the 288 private universities make the top 150.

The ranking is led by the National Seven Universities – a group of institutions founded by the Empire of Japan between 1886 and 1939, and run by the imperial government until the end of the Second World War.

Along with Tokyo, Tohoku and Kyoto, this alliance includes Nagoya University (joint fourth), Osaka University (sixth), Kyushu University (seventh) and Hokkaido University (eighth).

Tokyo Institute of Technology, founded in 1929 as an institution dedicated to science and technology, is the only outsider to make the top eight, in joint fourth place. It beats all the National Seven universities when it comes to its proportion of international students (10.7 per cent).

Search for university jobs in Japan

Analysis of the data reveals that most of the National Seven feature in the top 10 per cent of the 406-strong group when it comes to their resources (income, research output and students’ scores in the national mock university entrance exam) and reputation among academics, employers and careers advisers, but are held back by their proportion of international students and staff.

Just three institutions stay in the top 10 per cent across all four pillars of the ranking: Nagoya, Osaka and Tsukuba.

Meanwhile, there are seven universities that make the top 100 and are in the top 20 per cent when it comes to the engagement and outcomes pillars, despite the fact that they feature in the bottom 20 per cent for the finance per student metric. These are Doshisha University (35th), Nanzan University (joint 55th), the University of Kitakyushu (62nd), Toyo University (joint 76th), Ryukoku University (joint 80th), Kyoto Sangyo University (88th) and Kanagawa University (joint 89th).

Top 10 institutions in the THE Japan University Ranking

| Rank | University | Prefecture |

| 1 | University of Tokyo | Tokyo |

| 2 | Tohoku University | Miyagi |

| 3 | Kyoto University | Kyoto |

| =4 | Nagoya University | Aichi |

| =4 | Tokyo Institute of Technology | Tokyo |

| 6 | Osaka University | Osaka |

| 7 | Kyushu University | Fukuoka |

| 8 | Hokkaido University | Hokkaido |

| 9 | University of Tsukuba | Ibaraki |

| 10 | Waseda University | Tokyo |

View the full results for the Times Higher Education Japan University Rankings 2017

Island currents

Teaching at Japanese universities is “not really serious”, according to Akihiko Kimijima, dean of the College of International Relations at Ritsumeikan University in Kyoto.

This is because Japanese citizens are typically evaluated by their peers on the basis of the university to which they were admitted, rather than on their academic performance, he says. And once admitted, most students graduate with little difficulty.

“Japanese universities are traditionally a place for [students to have] free time,” he explains.

Susan Burton, a PhD student at the University of East Anglia’s School of Literature, Drama and Creative Writing, recently spent 10 years as an associate professor in several Japanese universities. In her experience, “asking questions in class, questioning the teacher and debating” do not typically feature in the country’s universities. In that sense, Japan’s higher education system “is a perfect system for producing educated and obedient workers for Japan Inc”.

However, Kimijima says that these traditions are gradually changing, and the country’s universities are looking to improve teaching.

A spur for some of this shift has come from the government. The Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports and Science and Technology now requires all universities to conduct student evaluations, according to James McCrostie, associate professor at Daito Bunka University, where he teaches English as a foreign language. But even if this initiative raises teaching standards, McCrostie points out that it will not necessarily threaten the established hierarchy of universities given that another entrenched characteristic of the Japanese university system is the link between institution attended and graduate job gained.

“Students don’t pick a job: they pick a company, such as Toyota or Sony. To get a job at one of those, you have to get into a really well-known university,” he explains. “If you go to a no-name small, private university, you will work for a no-name small, private company…If you go to The University of Tokyo, you’ll get your pick.”

In a recent opinion article for THE, Akiyoshi Yonezawa, director of the Office of Institutional Research at Tohoku University, complained of Japan’s “sclerotic labour market, in which most companies still prefer to hire fresh bachelor’s or master’s degree graduates from selective universities and train them in-house”.

The University of Tokyo has been ranked Japan’s top research-intensive university in every edition of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings since they began in 2004. It also heads the inaugural THE Japan University Ranking, produced in partnership with the Japanese education company Benesse and published today.

Unlike THE’s World University Rankings, this list of the top universities in Japan does not focus primarily on research performance. Instead, it is modelled on the inaugural Wall Street Journal/Times Higher Education US College Ranking, which was published in September 2016 and ranked more than 1,000 US universities and colleges.

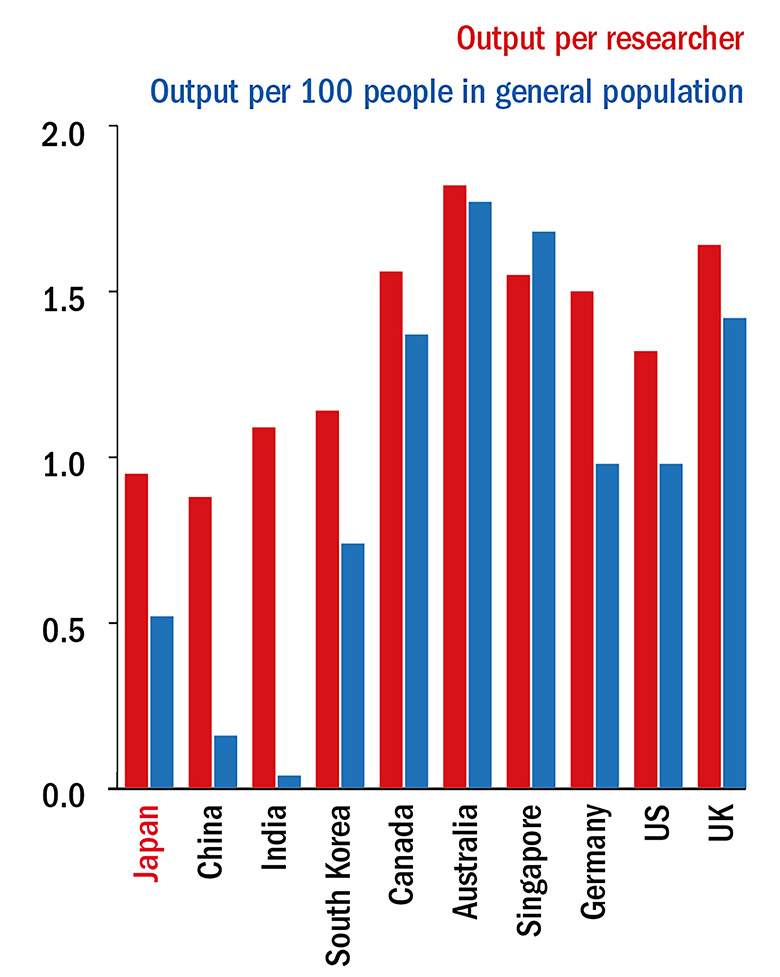

Productivity

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool

Like the US ranking, the Japan table is based on four broad “pillars” that focus primarily on what the institutions offer students. These are resources, engagement, outcomes and environment (see methodology). THE has also produced tables listing the top 20 institutions in each of these pillars, based on a database of more than 400 universities.

Clustered at the top of the ranking are the National Seven Universities, a group of institutions founded by the Empire of Japan between 1886 and 1939 and run by the imperial government until the end of the Second World War. Considered the Japanese equivalent of the US Ivy League, the select group comprises The University of Tokyo (UTokyo), Tohoku University, Kyoto University, Nagoya University, Osaka University, Kyushu University and Hokkaido University. The Tokyo Institute of Technology, founded in 1929, is the only non-member to break into the top eight of the ranking (at joint fourth place). Tokyo’s Waseda and Keio universities are the top private institutions, at 10th and 11th, respectively.

The success of these institutions is largely down to their strong research performance, their students’ high scores in the national mock university entrance exam and their reputation among top scholars and employers. Indeed, just three universities outside the overall top 20 feature in the top 20 for the outcomes pillar, which measures the esteem of institutions based on the annual THE Academic Reputation Survey and on a new survey of human resources departments from almost 600 publicly listed companies in Japan.

The president of UTokyo, Makoto Gonokami, attributes part of his institution’s success in the rankings to its unusual undergraduate structure – students receive a liberal arts education at a campus in the southwest of the city during their first two years, before transferring to a campus in the north of the city to specialise. As for Kyoto’s top three placing, its president, Juichi Yamagiwa, singles out its low student-to-staff ratio of 6.5.

Student-to-staff ratio is included in the resources pillar, alongside university income per student, research output and grants per member of staff, and students’ scores in the mock entrance exam (actual entrance exams are set by the individual universities, so they do not allow easy national comparisons). But, interestingly, resources alone do not guarantee favourable results in the table. Many of the institutions that sit atop this pillar are medical universities that are ranked relatively lowly overall in the Japan University Rankings, such as Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) (first for resources but only 38th overall), Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (fifth and 92nd) and Sapporo Medical University (10th and 111-120). This largely reflects their high levels of funding per student and low staff-to-student ratio. These institutions perform much less impressively on the other three pillars.

View the Japan University Rankings 2017 methodology

The pillars on engagement and environment provide a glimpse of some of the less prestigious Japanese institutions that are excelling when it comes to developing students’ abilities and providing an international environment for them to study in.

For instance, the engagement pillar, which reflects how well universities develop their students’ abilities and whether they are taught to global standards, based on a survey of careers advisers from almost 2,400 Japanese high schools, is headed by Akita International University, a municipal public institution ranked 20th overall. And the environment pillar, which looks at proportions of international students and staff, is topped by Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University (APU), a private institution from Beppu, ranked joint 24th overall.

APU’s president, Korenaga Shun, says that the institution was founded in 2000 with the aim of recruiting half of all students and faculty from abroad, and of having 50 countries represented on campus.

“If the number of international students is [only] 10 to 20 per cent, they become a minority, and any classes taught in English become translations of material intended for Japanese students and are not appropriate for international students,” he explains.

He adds that being highly international “brings cultures, values and language from around the world into our classrooms and research”.

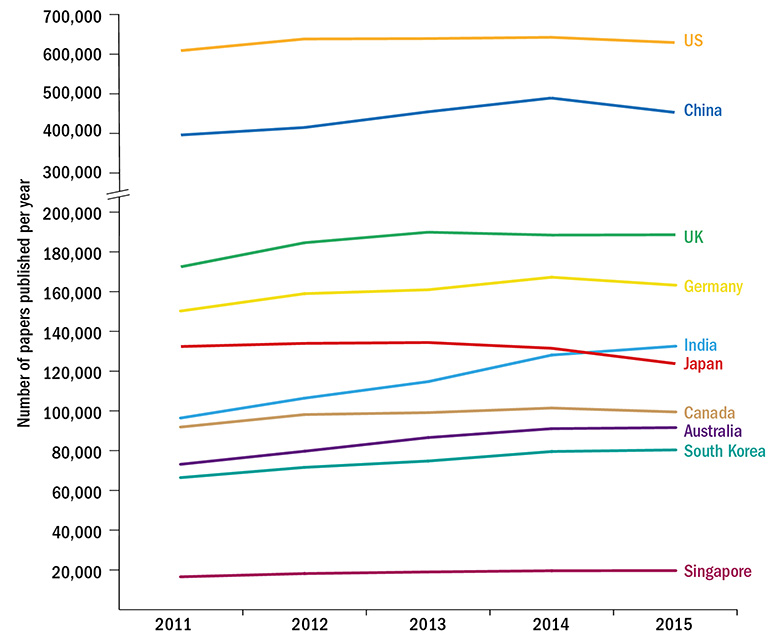

Productive measures? Trends in output

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool

According to THE’s data, 46.5 per cent of the university’s students are international: far more than any other Japanese institution (the next highest is Meikai University, with 14.9 per cent).

APU also has the second highest proportion of international staff among all ranked universities: 49 per cent.

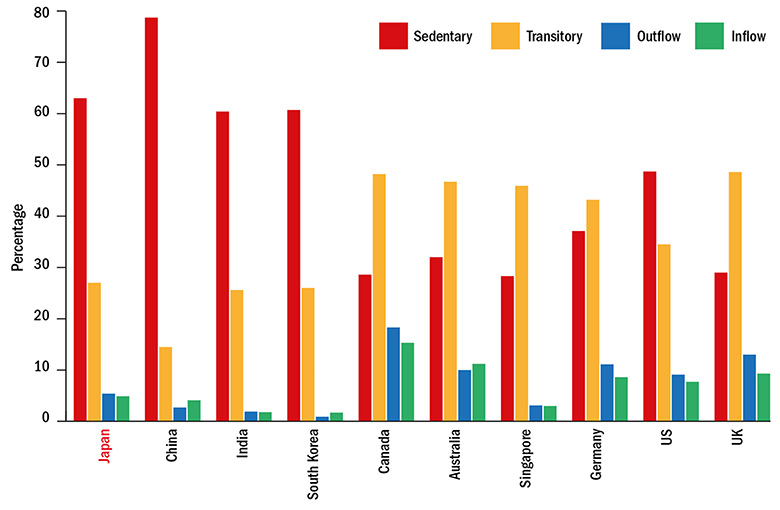

Japanese universities are notoriously poor when it comes to internationalisation. The country has just over 150,000 international students, who comprise less than 5 per cent of its overall student population, according to 2015 data from the Institute of International Education (IIE) – compared with 21 per cent of students in the UK, for instance, and 11 per cent in the Netherlands. Almost half these (49 per cent) come from China. The US is the top sending country outside Asia, but it accounts for just 1.5 per cent of Japan’s total overseas student cohort. Meanwhile, little more than 80,000 Japanese studied abroad in 2015, almost a quarter of whom went to the US. The country fares little better when it comes to the mobility of its researchers. Of the 260,000 active Japanese researchers between 1996 and 2014, almost two-thirds (63 per cent) have never published with affiliations outside Japan during this period, according to Elsevier’s SciVal tool. This compares with just 29 per cent of UK academics (see graph above).

Meanwhile, only 4.9 per cent of researchers in Japan have worked elsewhere for at least two years before moving to Japan, while a similarly small proportion (5.4 per cent) are based abroad after working in Japan for at least two years.

McCrostie, a Canadian, says that he used to think that foreign researchers were treated differently in Japan, with many English teachers on short, non-renewable contracts while their local colleagues enjoyed tenure. But he says that this has changed over time.

“A lot more universities are hiring foreign professors, while a lot more Japanese are hired on temporary contracts,” he says, explaining that the latter trend is largely a cost-cutting exercise.

UEA’s Burton adds that being an expat academic in Japan “can be quite lonely and isolating. You could work in universities and never see another foreign face in the faculty.” Universities were “created for the Japanese by the Japanese. Foreign academics and students who come in do so as guests, and the assumption is that they will eventually leave.”

Burton adds that she expected the percentage of foreign scholars in the country to rise after she left in 2013, but, on her annual visits back, she is told there has been no change.

However, the Japanese government is providing funding for institutions to improve in this area. In 2009, the country launched its Global 30 project to encourage 300,000 young foreigners to study at Japanese universities by 2020, and several institutions began offering undergraduate programmes taught wholly in English. Then, in 2014, this initiative was replaced with the ¥7.7 billion (£55 million) Top Global University project, which aims to help position more of the country’s institutions in the top 100 worldwide by recruiting more foreign professors and students. And there is also a target for 120,000 Japanese students to participate in short-term study-abroad trips by 2020.

In 2015, The University of Tokyo, ranked 54th in the environment pillar, introduced a four-term academic calendar – a change from the traditional two-semester system – to allow students to engage in more short-term study-abroad programmes. Acknowledging that Japan is in the “early stages” of internationalisation, Gonokami says that the aim of recent initiatives is “not that Japanese universities become just like their Western peers” but rather that “as part of a diverse global higher education community, Japanese universities will be able to share their unique knowledge, and Japan’s unique culture, with a connected and involved world”.

He adds that for UTokyo, internationalisation is about “contributing to and preserving the great diversity of human culture and knowledge, and benefiting from the excellence born from that diversity”.

Meanwhile, Nagaoka University of Technology, ranked 25th for environment, has been running joint degree programmes for 20 years with eight universities in five countries: Vietnam, Mexico, China, Malaysia and Mongolia. The first half of the degree is studied in students’ home countries while the second half is in Japan. A similar initiative takes place at the graduate level, in partnership with seven universities, and there is an international postgraduate course for working professionals conducted in English, according to the institution’s president, Nobuhiko Azuma.

Nagaoka, ranked only in the 801+ range in the World University Rankings, could be considered a prime example of the kind of Japanese university whose excellence and “strong domestic reputation” could be made more visible to an international audience by THE’s Japanese rankings, according to Tohoku’s Yonezawa. Ranked 17th overall, it tops the employer reputation survey, which asked human resources departments to identify the 10 best Japanese universities based on the strengths of their employees from those institutions. According to Azuma, its foundation in 1976 was intended to create more “practical and creative engineers and researchers” through strong cooperation between academia, industry and government. It recruits mainly graduates of KOSEN schools: a group of more than 60 five-year colleges of technology that admit students at age 15. This means that Nagaoka students have already been exposed to professional education from an early age and have “abundant hands-on and on-site experience at campus labs and industry”, says Azuma.

Engineers from industry do some of the teaching, and graduate students are involved in joint research projects with companies. All undergraduates must also undertake a six-month internship before beginning a master’s degree – a requirement that is unique in Japan, according to Azuma.

In addition, “virtual campuses” allow students and academics to find opportunities for research and exchanges with industry and government partners, while the institution has also sent many Japanese students to foreign universities and companies for six-month periods.

Beyond the academic benefits, there is another reason why universities in Japan are increasingly keen to internationalise. They need to make up for the decline in domestic student numbers resulting from the rapidly falling population of young people.

The total number of university students in Japan declined by 11 per cent between 2006 and 2015, according to IIE data, while Japan’s overall population fell by nearly 1 million between 2010 and 2015 to 127.1 million. According to the United Nations, Japan’s population will continue to shrink over the coming century, hitting 83 million by 2100 – when 35 per cent of citizens will be older than 65. Currently, just 13 per cent of Japan’s population is aged 0-14, compared with a world average of 26 per cent, according to the World Bank.

Japan has more than 4,000 higher education institutions, most of them private. And while some are very large – notably, Nihon University (67th overall) with 69,673 students and Waseda University with 51,373 – the majority are small. On average, universities in THE’s top 150 have just 9,830 students – making them particularly vulnerable to unfavourable demographic winds.

McCrostie notes that 2018 will be the first year when the number of 18-year-olds in the country drops dramatically. And while these demographic projections have been public knowledge for many years, the older professors and administrators at universities “who had all the power knew that they were retiring soon anyway, so there wasn’t much pressure to reform”, he says.

But not every institution will be hit equally hard, he predicts. “If your university is in Tokyo, you have a good chance of surviving because that’s where all the young people want to go. If your university is in the suburbs or, worse, in some small city, [you will] have real problems. One thing I’ve noticed is that a lot of universities are closing campuses in the suburbs and trying to open up downtown universities in Tokyo.”

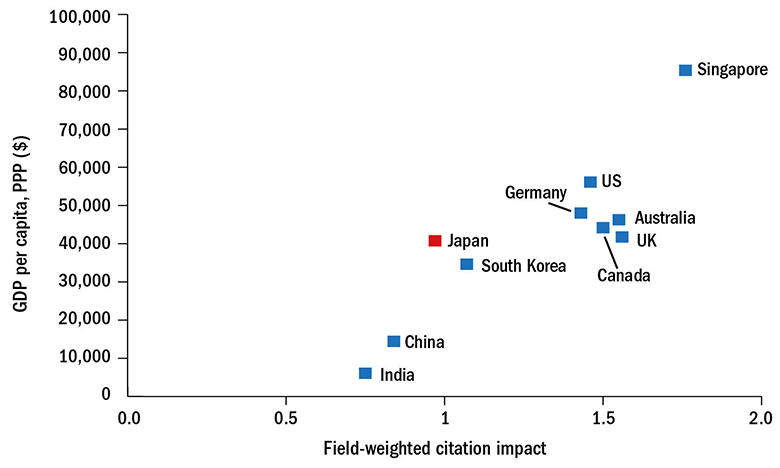

Research and riches: how quality and national wealth correlate

Sources: World Bank, Elsevier’s SciVal tool

Falling student numbers can also threaten standards because universities feel forced to lower entrance requirements to keep up enrolments. McCrostie says that this has already begun to happen – although he adds that the increased competition for students also means that there is more emphasis on “active learning” and improving teaching quality.

Kyoto’s Yamagiwa adds that the contraction of the Japanese workforce means that universities are required more than ever to play a significant role in “fostering individuals of high ability”. And his institution is committed to both increasing the recruitment of international students and providing continuing education programmes for mature students.

“Although there are somewhat short-sighted discussions of whether there are too many universities for the declining number of young people, it is more important for universities, in both urban and non-urban areas, to function as an intellectual infrastructure for the future of society,” he says.

Burton adds that many institutions in the country have been looking towards China to make up for a potential drop in domestic student numbers, but some of the small two-year colleges “preferred to close altogether” because they “realised that large numbers of Chinese students are an indicator that the university could be in financial trouble, so [its] reputation…goes down”.

Shigaku Tei, vice-president of the University of Aizu (23rd overall), which has seen an increase in student applications year-on-year between 2012 and 2017, says that one hindrance to maintaining or increasing student numbers is the enforced homogeneity of Japanese universities.

“If [the ministry] allowed universities to have more flexibility in decision-making, and if each university created their own features and specialities clearly and attractively, the universities could survive in spite of the declining number of young people,” he says.

The declining young population is also hampering institutions’ abilities to attract early career researchers. Tokyo’s Gonokami says that recruiting “the lifeblood of the university” has been a struggle in recent years, in part because Japan’s burgeoning debt has led to public funding for national universities being cut by about 1 per cent each year since 2004.

“As a result, it is vital that we…diversify our sources of funding to maintain our research and education at the highest levels of excellence and to recruit and support the next generation of academics,” Gonokami says.

In 2015, the Japanese government went so far as to write to the presidents of the country’s 86 elite national universities telling them to abolish their programmes in humanities and the social sciences, in favour of fields with “greater utilitarian value”. This led to many negative international headlines and a backlash from universities, prompting the education minister to claim, some months later, that the letter had been misinterpreted and that he merely wanted graduates “with skills to excel in a global environment”.

Who’s got the moves? Researcher mobility

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool, drawing on data from 1996 to 2014. Note: Sedentary = researchers have not published with affiliations outside Country X. Outflow = researchers first published in Country X and subsequently migrated for at least two years without returning OR researchers migrated to Country X from another country, stayed for at least two years, and then migrated to another country for at least two years without returning. Inflow = researchers first published in a different country before staying in Country X for at least two years OR researchers first published in Country X, migrated to another country for at least two years, then returned to Country X for at least two years. Transitory = researchers mainly published with affiliations in Country X and spent less than two years abroad before returning OR researchers published mainly from abroad and spent less than two years in Country X before migrating to another country.

Either way, science potentially offers universities a way to grow their incomes through partnerships and spin-offs. UTokyo, for its part, is extending its partnerships with industry to “expand the financial footing” of the institution and to “promote swifter and more efficient capitalisation on our research”, according to Gonokami. This is not just the university undertaking specific research projects with industry needs in mind, but rather tackling the whole research process together, from identifying issues to the social application of research outcomes.

For example, UTokyo is now working with both the information technology firm NEC and Hitachi to “uncover challenges” that were not previously apparent. And Gonokami insists that these arrangements avoid the usual researchers’ complaints about the impact of industry collaborations on their academic freedom.

“Rather than being controlled by powerful economic actors in pursuit of short-term results, researchers can share their own ideas, out of their own free will, with industry to discover what needs to be done,” he says. “Through this kind of free exchange of ideas, we hope to promote innovation that contributes to solving global issues and creating a better social system for all.”

A recent analysis by Futao Huang, a professor at the Research Institute for Higher Education at Hiroshima University, found that Japan’s top-ranked universities now rely on their affiliated hospitals for about 40 per cent of their income. And McCrostie says that reduced public funding has led to increased tuition fees at national institutions, and a rise in the number of Japanese students relying on loans.

Although the Japan University Rankings is focused largely on what institutions offer students, two of the 11 metrics take into account research performance – output per member of staff and grants per member of staff.

UTokyo is number one when it comes to the number of grants received per member of staff, while Toyota Technological Institute has the largest output per member of staff.

As a country, however, Japan fares poorly in comparisons with other developed nations in terms of research.

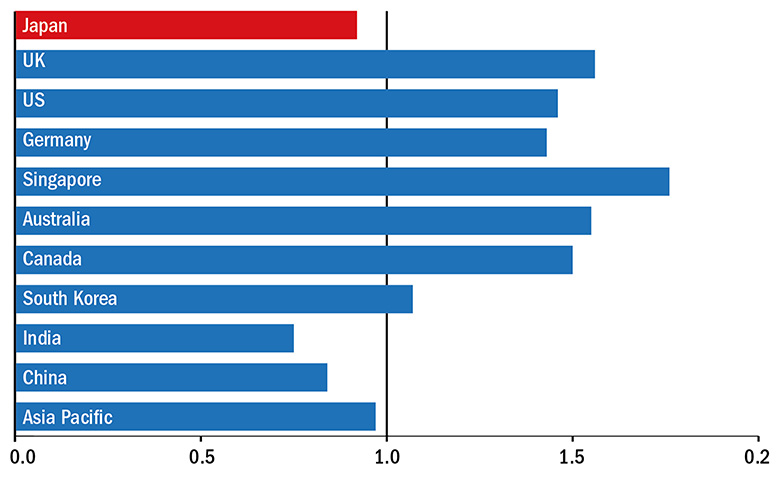

For example, when looking at the volume of research per academic, Japan trails not only other major developed countries but also India, and it falls below the average for Asia-Pacific as a whole, according to data from Elsevier’s SciVal tool. Japan is also the only country surveyed in which research output declined between 2011 and 2015 – despite an increase in the number of active scholars.

Japan also performs below the world average when it comes to average field-weighted citation impact – a measure of research quality – and it still lags behind many other developed nations when its gross domestic product per capita (a measure of national wealth) is taken into account.

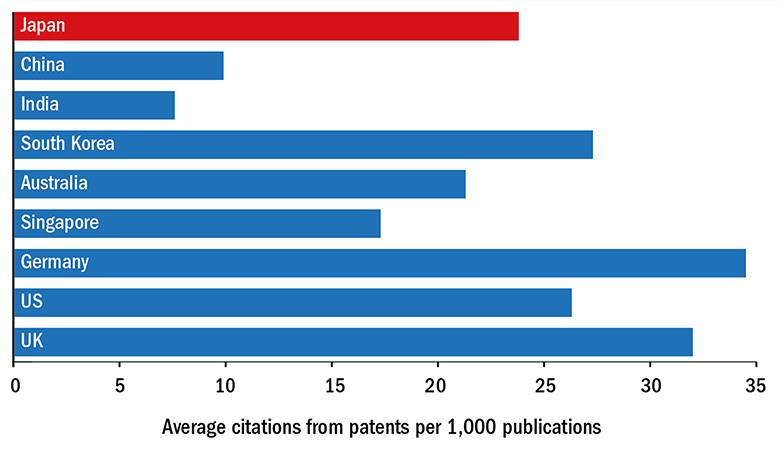

The country’s strongest areas in terms of publications are medicine, engineering, physics and biochemistry, while there has been a large growth in multidisciplinary papers and research on the arts and humanities. Its research also appears to be reasonably useful to industry by international standards, judged by the number of citations from patents.

Burton notes that one big drag on Japan’s international research reputation is that the written and spoken standard of English in the country is “very low”. “So while [Japanese academics] might consistently publish in Japanese, in their own journals, and go to “domestic” conferences, they won’t get the citations or recognition for their work unless it is translated. This is why when you hear about these Japanese Nobel prizewinners, you find out that they’re actually based at a university in the US. And the reason is because they’ve had to go abroad and work in English to get their work recognised.”

McCrostie adds that Japanese institutions have historically placed too much emphasis on research published in university bulletins, which is not peer-reviewed. However, he says, this culture is changing, in part because of tougher promotion requirements, and there is now more of a focus on getting published in top international journals.

Another issue in the past has been that university departments tended to hire their own doctoral graduates, which meant “your supervisor became your boss” and there was not much “challenging of ideas”. But McCrostie says that institutions are beginning to actively look more widely for the best candidates. And, overall, he is optimistic about the future for Japanese higher education.

“Japan has traditionally been very good at reinventing itself. It has changed direction massively a few times,” McCrostie says, citing the Meiji era between 1868 and 1912, which led to the modernisation of the country, and the period after the Second World War, when it rebuilt itself after being “bombed flat”.

“Japanese universities are kind of in a panic [and] not everyone is going to survive,” he admits. “But the universities that do are going to be a lot stronger and a lot better.”

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

High quality? Field-weighted citation impact

Note: 1 = world average

Big bangs? Impact assessments

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool