The University of Oxford has become the first UK university to top the Times Higher Education World University Rankings in the 12-year history of the table. It knocks the five-time leader, the California Institute of Technology, into second place in the World University Rankings 2016-2017.

Oxford’s success can be attributed to improved performances across the four main indicators underlying the methodology of the ranking – teaching, research, citations and international outlook. More specifically the institution’s total income and research income is rising faster than its staff numbers, its research is more influential, and it has been more successful at drawing in international talent.

But when looking at country level, nations in Asia stand out. Two new Asian universities make the top 100 (Chinese University of Hong Kong and Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST)), while another four join the top 200: City University of Hong Kong, University of Science and Technology of China, Fudan University and Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Furthermore, China’s two flagship universities have both made gains – Peking University joins the top 30 at 29th (up from 42nd last year), while Tsinghua University joins the top 40 at 35th (up from joint 47th). Asia’s leading institution, the National University of Singapore, is at 24th – its highest ever rank.

Meanwhile, India’s leading university – the Indian Institute of Science – is edging closer to the top 200, claiming a spot in the 201-250 band, its highest ever position.

- Standing still is not an option for the World University Rankings

- Higher education’s diverse mission

- Keep the UK’s doors open to students and scholars

- Burgeoning rankings list has BRICS struggling to keep pace

Overall, 289 Asian universities from 24 countries make the overall list of 980 institutions and an elite group of 19 are in the top 200, up from 15 last year.

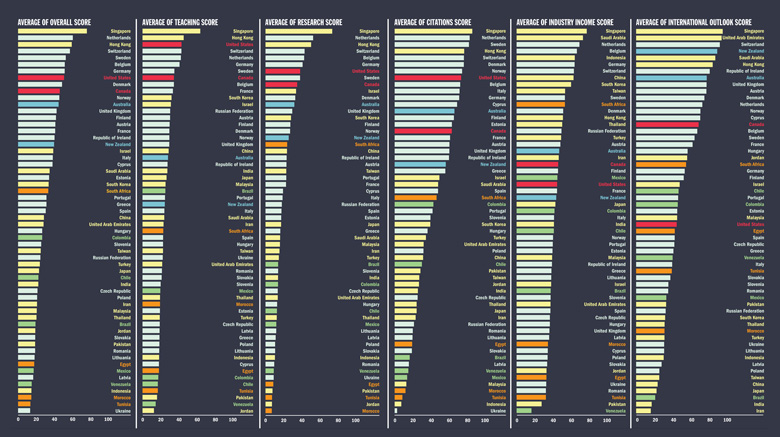

When analysing which countries achieve the highest average scores, Singapore comes top on all five of the pillars underlying the ranking – teaching, research, citations, industry income and international outlook. Hong Kong is second for teaching, third for research and fourth for citations.

Rajika Bhandari, deputy vice-president of research and evaluation at the Institute of International Education and co-editor of the book Asia: The Next Higher Education Superpower?, said that the “sharp rise” of Asia’s universities is due to three main factors: rapidly growing populations and demand for higher education in the region; governments making “significant investments” in universities; and improvements by individual institutions.

On advances at university level, she said that many Asian scholars who studied at Western universities are now academics in their home countries and have “really begun to transform their own higher education sectors”.

They have “brought back to [their] home campuses some of the teaching values of critical thinking and liberal education, as well as the idea of promotion based on merit and research outputs”, she said.

- The nine challenges global HE must confront over the next five years

- Why it’s hard to make global comparisons in higher education

- Books included in World University Rankings analysis for first time

- World University Rankings 2016-2017 passes independent audit

- Search for jobs at the world's top universities

She predicted that there will be continued expansion of cross-degree and campus partnerships among institutions in Asia and the West, as well as a “huge push towards intra-regional higher education partnerships and mobility within the Asia-Pacific region”.

However, Richard Robison, emeritus professor in the Asia Research Centre at Murdoch University, said while there are a “small number” of Asian universities “making international strides”, many are much further behind.

When asked whether he envisioned some Asian universities competing with the likes of Oxbridge and the Ivy League, he said: “I can’t see them becoming giant intellectual hubs that some big Western universities have become over a couple of hundred years because they have a different idea about education and a different way of going about it.”

He said that Asian universities create a “very pressured environment”, have “a lot of learning by rote” and there is “not a lot of discussion in classes”.

“I don’t know if that would translate globally, except in some of the narrow scientific and technical areas,” he said.

Claim a free copy of the World University Rankings 2016-2017 digital supplement

World University Rankings 2016-2017: top 10

| 2016-17 rank | 2015-16 rank | Institution | Country |

| 1 | 2 | University of Oxford | United Kingdom |

| 2 | 1 | California Institute of Technology | United States |

| 3 | 3 | Stanford University | United States |

| 4 | 4 | University of Cambridge | United Kingdom |

| 5 | 5 | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | United States |

| 6 | 6 | Harvard University | United States |

| 7 | 7 | Princeton University | United States |

| 8 | 8 | Imperial College London | United Kingdom |

| 9 | 9 | ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich | Switzerland |

| =10 | 13 | University of California, Berkeley | United States |

| =10 | 10 | University of Chicago | United States |

Browse the full list of the world's top-ranked universities in 2016-2017

The University of Oxford’s people power is the key to its success

How does an institution achieve the top spot in the World University Rankings? The key is to invest in talented staff, Oxford’s vice-chancellor tells Ellie Bothwell

You might think that achieving the aim of becoming one of the world’s top universities would require the implementation of a detailed and multifaceted strategy, encompassing the building of deep international partnerships, securing funding, forging strong relationships with alumni and producing innovative teaching and research.

But the vice-chancellor of the University of Oxford says that maintaining its position as one of the best universities in the world is “really quite simple”; it comes down to recruiting the best talent.

“Any university is only as good as the academics it can attract,” says Louise Richardson, who became Oxford’s leader in January after serving at the helm of the University of St Andrews for seven years.

“The best academics attract other top academics as well as smart early career academics. They attract the best students and the most competitive research funding, so it really is a virtuous circle. The key is for universities to provide an environment in which these academics are valued, in which young academics are supported and in which all are free to set their own research agendas.”

Oxford has certainly achieved those goals. The institution has topped the 2016-17 Times Higher Education World University Rankings, becoming the first UK university to reach pole position in the 12-year history of the ranking. It knocks the five-time champion, the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), into second place.

Oxford’s achievement is down to an improved performance across the four broad performance “pillars” underlying the methodology of the ranking – teaching, research, citations and international outlook. Its advances since last year include total income and research income outstripping the growth in staff numbers; greater research impact; a higher proportion of international staff and students as well as fewer students per member of staff and more PhDs awarded. Oxford’s total income today stands at £1,429.3 million.

Richardson says that key objectives for the institution have been “to take nothing for granted, to be constantly open to innovation and adaptation and to continue to invest”.

“Oxford today, for example, places far more emphasis on the sciences than it has done historically, as seen in our expansion of the Science Park at Begbroke and our new physics building. We are also going into new areas such as creating the first School of Government in the UK,” she says.

Higher education quality quantified

How do institutions come to be ranked among the world’s top 200? A closer look at some of the average indicators for those at the very peak of this year’s list may provide the answers

Despite Oxford’s eye-catching move into first place this year, the results at the summit of the rankings are remarkably stable. Stanford University, the University of Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Harvard University, Princeton University, Imperial College London and ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich hold on to their positions between third and ninth place, respectively.

The University of Chicago remains in joint 10th position, together with the University of California, Berkeley, which climbs three places.

Oxford achieves the highest score for research, while Caltech leads in teaching. Stanford and MIT are in joint second place for citations, behind the highly focused medical institution St George’s, University of London.

Marty Schmidt, MIT’s provost, cites his institution’s focus on attracting top talent and its diverse community – 42 per cent of its faculty were born outside the US, he says – as two key reasons for its strong research influence. But he says that the main factor is its interdisciplinary approach, which is fostered through interdepartmental laboratories, shared facilities and initiatives centred on global problems.

“Working across disciplinary boundaries, working in a collaborative way, allows our faculty and our students to see opportunities that you might not otherwise see if you are working in a disciplinary silo,” he says.

This interdisciplinary approach exists at a student level, too; all undergraduates are required to take at least one humanities or social sciences subject per semester, regardless of their specialism.

Although THE’s rankings methodology remains largely unchanged since last year, there have been a few small adjustments, including blending the reputation scores from the past two annual surveys and incorporating books among the research outputs assessed for their impact.

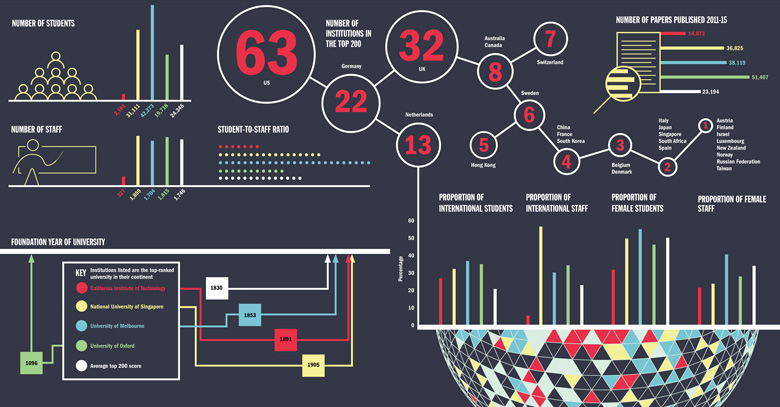

The top 200 remains steady. In total, the US still has 63 universities in this cohort, while the UK claims 32 places, two shy of last year’s sum.

Germany is once again the third most-represented country in the top 200, with 22 institutions (up from 20), while the Netherlands is still fourth, with 13 (up from 12).

However, while these Western countries continue to dominate the upper echelons of the ranking, Asia is becoming increasingly visible, with several of the continent’s institutions edging closer to the top 20.

Mainland China takes four places in the top 200, up from two last year, with its leader Peking University joining the top 30, in 29th place (up from 42nd last year), and its regional rival Tsinghua University making its debut in the top 40, in 35th place (up from joint 47th).

International picture

Analysis by each individual score highlights the stellar performance of Singapore across all factors, and shows the dominance of Europe and Asia in the World University Rankings

South Korea also has four representatives in the top 200, the same number as last year, but all have risen.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong claims five top 200 positions, up from three last year, making it the most-represented Asian region in the top 200. It is led by the University of Hong Kong in joint 43rd place, a modest hop up from joint 44th last year.

Singapore is still home to the continent’s top university, the National University of Singapore (NUS) in 24th place (up from 26th).

Lim Chuan Poh, chairman of Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research, says that with no natural resources in the city state, people are its only asset, and the government has therefore sustained commitment to invest in education since the nation’s independence in 1965.

“In the past 10 years, we have stepped up investments in our universities to transform them into research-intensive autonomous universities,” he says.

“The focus of our universities is to provide the best education to students to prepare them for an increasingly dynamic and competitive global and regional environment. The universities must therefore be able to offer a conducive environment and the right conditions that can attract some of the best academics to conduct cutting-edge research and deliver world-class education.”

China’s rise can be partly attributed to its improved scores in the academic reputation survey, which underpins both the research and teaching indicators in the methodology. The country’s institutions have also improved their scores for citations and internationalisation.

Meanwhile, Hong Kong’s improved performance is largely owing to increased institutional and research income and greater research productivity.

Francisco Marmolejo, the World Bank’s lead tertiary education specialist, says that the East Asian region has made “remarkable progress” in terms of access to and the quality of higher education. He cites the growth of private funds to universities as one of the main factors contributing to the rise of China and Hong Kong.

Will an Asian university reach the top 10 of the rankings in the near future?

Marmolejo says that there is no doubt that this will happen, but adds: “How fast and who will arrive first? Nobody can predict that.”

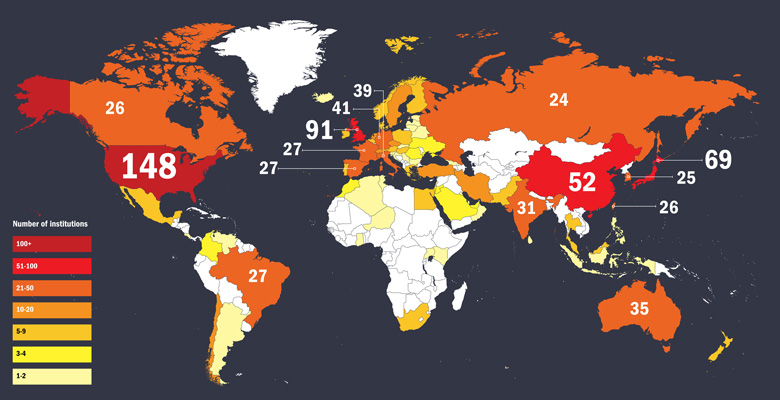

Global hotspots

We map university density on an international scale

Notes: the figures on the map refer to the top four countries with the highest number of institutions. The countries in white are those with no institutions in the 2016 ranking

However, he warns that the region’s ageing population poses a potential threat to its higher education success.

“The only exceptions in the entire region as a whole are India, Bangladesh and Pakistan. Other than that, the entire region is suffering from a significant decline in the younger population,” he says. “It will have a significant impact on the landscape of higher education in the region. How large this will be we will have to see.”

Oxford’s Richardson adds that Asian universities are one of the institution’s main future competitors, owing to their “massive government investment”, alongside American universities with “eye-watering endowments”.

She cites finance as the biggest threat to Oxford’s pre-eminence.

“We, frankly, do not have the resources commensurate with our global position,” she says.

“We are also more tightly regulated than many of our global competitors. I’ve seen no evidence to suggest that all these regulations improve the quality of what we do, and yet they are a major distraction of time and resources.”

In particular, she is concerned about the impact the government’s forthcoming teaching excellence framework, which will monitor and assess the quality of teaching in England’s universities, will have on Oxford’s one-on-one approach to teaching.

“I do worry that the forthcoming TEF may be inclined, as most regulations are, to attempt to enforce conformity across the sector and fail to appreciate the value of its diversity and, in particular, the value of unique approaches like ours,” she says.

Oxford is also working hard to limit damage after the UK’s vote to leave the European Union, by reassuring EU staff and students that they are still welcome and minimising the impact on research funding, 12 per cent of which, at Oxford, comes from the EU.

“We have innumerable examples of academics being frozen out of collaborative research projects, withdrawing from job searches, and burnishing their CVs with a view to moving to an institution where their funding will be secure. This is the piece that worries me most,” she says.

She concludes that a key future priority for Oxford will be to engage more with the public.

“I find it sobering that the [EU exit] referendum voting patterns reveal such a gap between universities and elite institutions generally and broader British society. We need to address this.”

To raise your university’s global profile with Times Higher Education, please contact branding@timeshighereducation.com

To unlock the data behind THE’s rankings, and access a range of analytical and benchmarking tools, contact data@timeshighereducation.com