The rise of high-quality automated translation may be the latest threat to the viability of modern language degrees, but it is far from the first. The decline of these time-honoured university subjects has been lamented for at least two decades.

In the UK, several cash-strapped universities have recently contemplated closing their modern languages departments, often as part of a wider downsizing of humanities degrees. The universities of Kent and Aberdeen may have fully and partially rowed back on plans to close their language degrees, but others, such as the University of Hull and Leeds Beckett University, have followed through. Applications for voluntary redundancy at Queen Mary University of London, meanwhile, are being particularly encouraged from the Schools of English and Drama and the School of Languages, Linguistics and Film, though the university stresses that the changes are driven not by financial struggles but by the need to meet "the demands of future students" and to "deliver leading research to address the ever-changing challenges facing society".

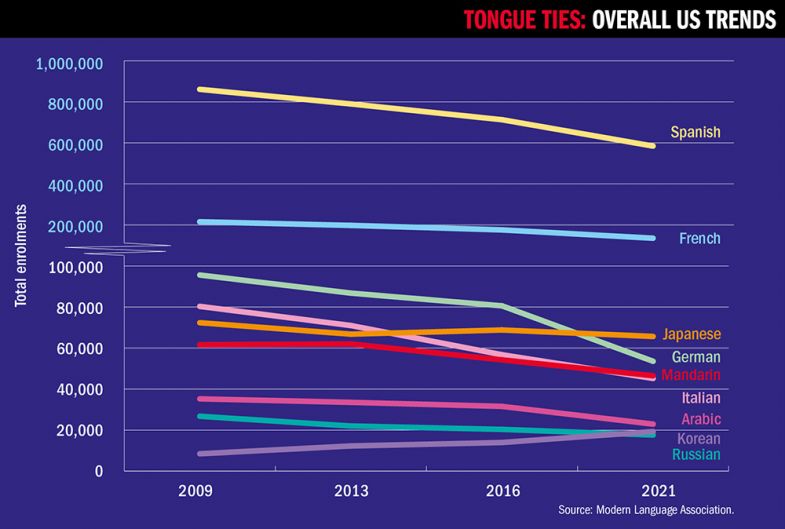

In Australia, Indonesian language programmes have been closed in recent years at La Trobe and Western Sydney universities, while the Swinburne University of Technology closed three language courses in 2020 as part of Covid cost-cutting measures. More recently, Macquarie University proposed ditching more than half of its language programmes. And in the US, colleges and universities closed 651 foreign-language programmes from 2013 to 2016 and 961 between 2016 and 2021, the latter amounting to a drop of 8.2 per cent, according to reports by the Modern Language Association (MLA).

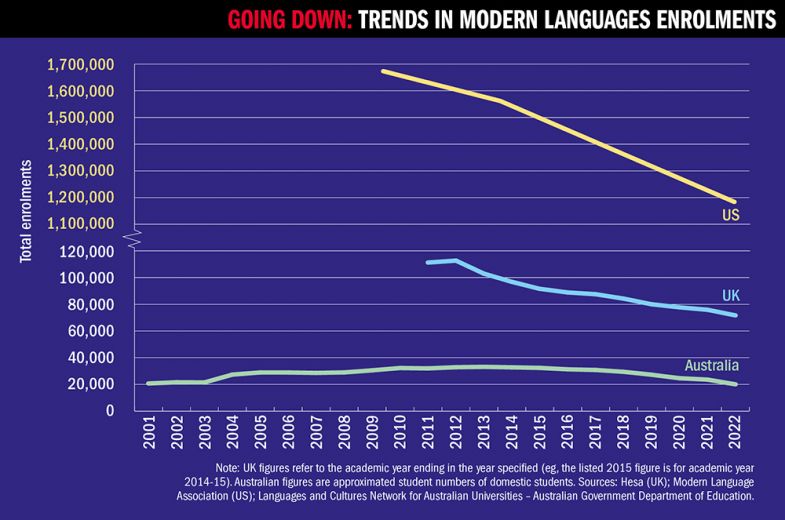

The basic problem is student demand. Figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that only 71,690 UK students were taking language courses in 2021-22. This was 6 per cent down on the year before and 36 per cent down on 2010-11. The number of students on French studies courses has declined by 33 per cent since 2014-15, while there were declines of 29 per cent in German and 26 per cent in Italian.

Separate data from the admission service Ucas shows that the 17 per cent decline in applications to study modern languages at UK universities between 2018-19 and 2023-24 was the largest drop of all 21 subject areas it monitors – although some insiders point to the rise of joint or combined honours degrees as evidence not so much of decline as of evolution of modern languages.

In Australia, meanwhile, the latest figures from the Languages and Cultures Network for Australian Universities show that 15 per cent fewer students studied languages in 2022 compared with 2021, and the total of just over 20,000 full-time equivalents was the lowest level since records began in 2001. The data shows a fall in every language category between 2021 and 2022 except Australian Indigenous languages.

It is a similar picture in the US, too. Analysis of the latest MLA data shows that total language enrolments on US college campuses decreased by 17 per cent between 2016 and 2021, marking the largest decline in the history of the census. By contrast, from 1980 until 2009, language enrolments saw strong growth in the US, but total enrolments have now fallen back to 1998 levels.

The MLA attributes this fall in part to the overall decrease in the number of students entering US colleges and universities. But the picture is clearly much more complex than that, with a potent cocktail of wider and long-term trends combining with the technological explosion to put the study of modern languages at particular risk.

One of those trends is a general turn away from the humanities and the social sciences, in an era in which the rising costs of higher education for both students and governments have focused attention on employability. While Kent ultimately spared its modern languages degrees, it followed through on plans to cut anthropology, philosophy, journalism, art history, health and social care, and music and audio technology. More generally, the many job cuts currently being made across the UK sector are focused primarily on the humanities.

Those cuts are being driven by the decline in the value of domestic student funding. That decline has led many universities to try to compensate by recruiting more international students. But, according to Emma Cayley, chair of medieval French and head of the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies at the University of Leeds, this has been harder to do for languages departments – as well as English and history departments – because they traditionally attract a preponderance of home undergraduates.

Cayley says modern languages have much to learn from Classics, which has reinvented itself in recent years, doing “incredible work” on broadening its curriculum and widening participation. But Ruth Whittle, associate professor in modern languages at the University of Birmingham, points out that widening participation efforts are hampered by the effective rise in the cost of studying languages in England caused by the diminishing value of student maintenance loans. This makes it a “tall task” for languages students to support themselves during their year abroad: “The gap between what students are able to afford and what is actually needed in the bank is tremendous,” she says.

Language provision is also costly for universities. Peter Hurley, associate professor at Melbourne’s Victoria University, says some Australian institutions have been moving out of the disciplines because high-quality instruction depends on small class sizes, making economies of scale difficult to achieve. “It is a reality in any institutional environment that small student numbers make it difficult to run courses,” he says.

Another factor is government policy. Academics in the UK are near unanimous that the 2004 decision by the Labour government to make learning a language optional in England after the age of 14 was disastrous for university language departments. Between 2007 and 2013, for instance, 11 UK universities closed their language departments, according to an investigation by The Guardian. And Sascha Stollhans, associate professor of language pedagogies at Leeds, worries that “rigid” assessment of languages in UK schools creates the impression that students are less likely to get good grades if they study them to GCSE and A level. This contributes to a “vicious” knock-on effect, whereby fewer A-level students means fewer graduates and fewer qualified schoolteachers.

But Cayley says a narrative of terminal decline is counter-productive, and universities have tried to fix pipeline problems by introducing ab initio degrees, which do not require applicants to have studied the language at school.

Languages are not mandatory in US schools either, and reduced provision has led many colleges and universities to eliminate language ability as both an entrance and graduation requirement, according to Deborah Cohn, provost professor in the department of Spanish and Portuguese at Indiana University. “This, in turn, had the knock-on effect of further disincentivising high school-level language study,” she says.

And, in Australia, Liam Prince, director of the Australian Consortium for In-Country Indonesian Studies, has “argued the case repeatedly…that the problem of declining languages enrolments in universities lies upstream, in schools”. He worries that the volume of formal language learning in Australia is determined not by students but by school administrators, and he urges universities, schools and politicians to work together to address the decline.

“I think it next to impossible for the Australian higher education system to solve this problem on its own, without a concurrent strategy and new government funding to address the falling rates of second-language learning at senior secondary level,” he says.

The perceived relevance of language study is also related to geopolitics. It might be expected that the current period of rising nationalism and isolationism would increase the political demand for expertise in the languages and cultures of competitor and enemy nations. As Geoffrey Miller, a doctoral candidate in politics at the University of Otago, puts it, language graduates are key instruments in any “diplomatic or intelligence toolkit”, so “any decline in foreign language learning at schools and universities will ultimately affect the pipeline of graduates available for recruitment by foreign and defence ministries”.

But Michael Kelly, emeritus professor of French at the University of Southampton, has tracked the steady decline of languages in UK higher education over the past 30 years and says this trend was “sharpened by the spike in nationalism around Brexit” – although it affects different languages in different ways. One reason might be narrowed international employment opportunities; Birmingham’s Whittle says her UK students now have difficulties seeing themselves working in Europe because of post-Brexit visa regulations, for instance.

Charles Forsdick, Drapers professor of French at the University of Cambridge, says that, internationally, a diverse range of language provision is usually a result of coordinated government support, including for lesser-taught but strategically important subjects.

“The lack of any such approach in the UK means that the provision of languages is primarily subject to perceived student demand and at the whim of institutional autonomy,” he adds.

Yet the direst potential consequences of this lack of strategic oversight are averted by the fact that the UK and other anglophone nations continue to attract many English-speaking immigrants who also come with fluency in their mother tongues. Miller, who is also a geopolitical analyst at New Zealand’s Democracy Project, says his country’s foreign ministry favours the “cheaper” option of recruiting bilingual speakers and local staff to run its foreign missions. And, according to Tomasz Kamusella, reader in modern history at the University of St Andrews, the prevalence of such immigrants in the US and UK contributes to those countries’ neglect of formal language provision. But, in his view, diplomatic reliance on immigrants is “obviously fraught with danger” since they can be “sleeper [agents] who…play loyal, patriotic citizens…but are actually working for a foreign power”.

The attractiveness of the anglophone world to immigrants is, of course, intimately related to the hegemony of the English language. And while the learning of some languages is in global decline, Southampton’s Kelly says the rise of nationalism “hasn’t turned back the tide of English so far – even in France, which has always had a reflex against ‘Anglo-Saxon’ dominance”. Indeed, according to Kamusella, “The acquisition of English by people outside of English-speaking areas is all the time on the rise, so, from the global perspective, there is no decline whatsoever in the teaching of languages.”

In Denmark, for instance, academics have warned of “language death” after the closure of scores of foreign language programmes, blaming the trend on a lack of regard for the humanities – but also on the perceived overwhelming importance of English compared with other tongues.

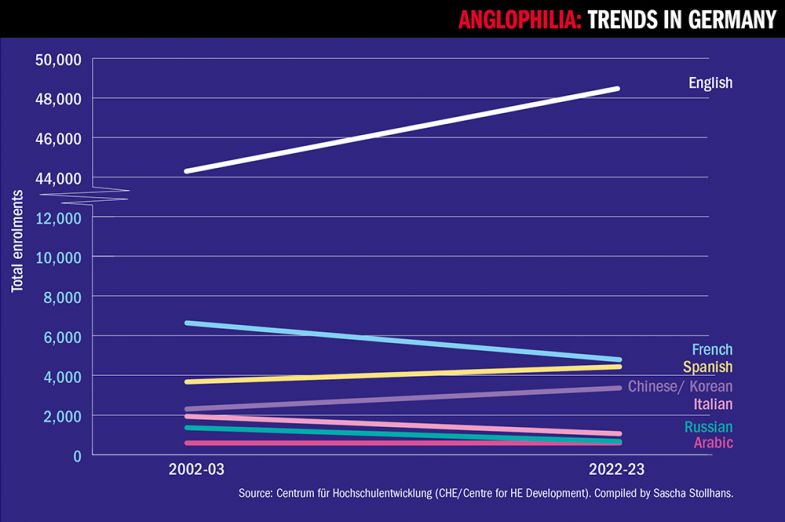

In Germany, the picture is more mixed, however. Figures from the Centre for HE Development show that the number of students taking English courses at German universities is rising, but there were also increases between 2002-03 and 2022-23 in Spanish studies (21 per cent), Chinese/Korean studies (46 per cent) and Asian studies (103 per cent). By contrast, there were decreases for French (28 per cent), Italian (45 per cent) and Russian (51 per cent).

“I don’t see the German context developing in the same direction as the UK context due to the significance of languages in the primary and secondary sectors, as well as, generally, a slightly different perception of languages,” says Leeds’ Stollhans. But Nicola McLelland, professor of German and history of linguistics at the University of Nottingham, says the popularity of English has created an “unequal playing field” in Germany too, as it has in the Netherlands.

“I don’t know that they are at the point of cutting courses yet, but there is certainly a big shift in Germany and many other parts of Europe…to English being the main language of interest for students,” she says. Currently, 49,000 students are studying English at German universities; the next most popular language course, French, has just 5,000 enrolments.

Sabine Doff, professor of English language education at Bremen University, agrees that there is a negative trend for many languages other than English at German universities, and she sees French studies as being in “crisis”.

“Even at large universities that previously covered the spectrum of modern philology subjects, the closure of…departments…is now being discussed,” she says. “This has already been partially implemented at some medium-sized locations. In Bremen, for example, there has been no Italian studies for years.”

The ever-greater dominance of English-learning internationally also has implications for modern languages departments in anglophone countries since it diminishes the perceived need for English-speakers to learn other languages to communicate internationally, limiting both the personal and market value of language degrees. Birmingham’s Whittle says the assumption that “everyone” speaks English has been particularly prevalent in the UK since Brexit.

However, this perception is not inevitable. In Ireland, about 4 per cent of students in higher education study a language other than English or Irish, compared with less than 1 per cent in the UK, according to Jennifer Bruen, professor of applied linguistics and German at Dublin City University. And Irish universities are setting their sights higher still. The country’s membership of the EU means that working or studying in another EU country is a more likely prospect, while engagement with speakers beyond the anglophone world naturally plays an important role in such a small, open economy, Bruen adds.

But does Ireland’s capacity to speak to its trading partners in their own languages really rely on degree-level language study? Technological advancements are leading many to question that assumption. And, taken together, these advancements may pose the biggest threats to university language departments' survival.

The popularity of the Duolingo language-learning app, whose basic functions are free to access, has had academics scratching their heads over the past decade about how, if at all, to respond. Beginning as a project by Carnegie Mellon University computer science students Luis von Ahn and Severin Hacker in 2011, Duolingo is now the world’s most popular language-learning app, with more than 80 million monthly users learning 42 languages (the most popular of which is, of course, English).

Richard Brecht, professor emeritus in the School of Languages, Literatures, and Cultures at the University of Maryland, concedes that Duolingo is “the best language app ever” and that “we don’t know what that did to [university] enrolments”. It may be, he adds, that while student numbers are declining, overall language learning outside formal environments may be going up. And, in the longer term, that might mean that formal courses will be able to ride on Duolingo’s coat-tails.

For her part, Cayley, who is also chair of the UK’s University Council for Languages, sees no opposition between higher education and language-learning apps. “The explosion of interest in Duolingo, especially during Covid lockdowns, has, in fact, served to heighten interest in language learning and demonstrate the appetite we have for exploring other cultures through that medium,” she says.

Despite concerns that Duolingo has changed learners’ mindsets about the commitment required for language learning – reducing it to something that can be done in bite-sized chunks in spare moments – Prince also thinks such “gamified language-learning platforms” have the potential to help reverse the decline of formal language study in anglophone countries, “particularly because they allow students to choose a language, or languages, in which they have an intrinsic interest and to proceed at their own individualised pace”. Offering those languages at university would “do wonders” for the diversity and retention of language learning in Australian universities, he adds.

Moreover, as Otago’s Miller puts it, “Diplomats and intelligence specialists require advanced levels of language skills that realistically can only be developed through rigorous training courses. In almost any country, universities are the natural and obvious centres of expertise for facilitating this instruction.” And, for Whittle, it is possible that people who learn languages using Duolingo may encourage their children to pursue such higher-level training. “On the other hand,” she adds, “I’ve also had students in the first year who have told me they had to defend their choice of studying modern languages” to friends and relatives who ask “Doesn’t AI do it for you?”.

Increasing numbers of businesses are taking the view that AI does indeed do it for them. Even before large language models exploded into the public realm at the end of 2022, the incremental improvements in digital translation tools such as Google Translate had already “changed fundamentally” the employment conditions of translators, Whittle says, with clients paying less and less for their services. In the UK, average earnings for an entry-level translator – which typically requires a postgraduate qualification – are now just under £28,000, while zero-hours contracts often pay only £14-15 per hour, she says.

“It shows that the value of high-quality language mediation is prized low and really needs to be promoted if that is to change,” she adds.

But how likely that is to occur is unclear now that ChatGPT and its ilk are pushing automated translation to new levels of fluency. Maryland’s Brecht, who is co-director of the American Councils Research Center at the American Councils for International Education, concedes that while formal research on the topic is scant, there is “no question that AI, Google Translate, ChatGPT…are making the need for language in the eyes of learners and their parents less critical”.

On the other hand, he thinks large language models have “the potential to help improve enrolments and language abilities” by offering excellent access to oral and reading practices in distinct areas of interest to learners, as well as tracking their progress in detail and building avatars to customise their learning experience. He is also excited by the capacity of AI to decipher and rescue written languages that were once thought lost.

Indeed, optimism generally abounds among linguists that modern languages degrees can coexist with large language translation models. For instance, they emphasise the fact that there is much more to a languages degree than language learning. For instance, while AI’s “massive advances” make it capable of translating routine documents, those using automated translation tools still need to be fairly confident in the language and, importantly, have a certain “cultural competence” to proofread the finished product, according to Alex Mangold, a modern languages lecturer at Aberystwyth University.

Mangold concedes that university courses should evolve to take account of the fact that the role of translator, accordingly, is morphing into more of an editor's role, but he thinks linguists should shout louder about all the cultural knowledge and heritage that is absorbed during the study of a country’s language.

Cambridge’s Forsdick agrees on the need for linguistic expertise to be complemented with cultural knowledge. And while Duolingo reportedly fired 10 per cent of its human translators in January in a shift to AI, Forsdick insists that “far from reducing opportunities for employment, businesses in the AI field are hiring increasing numbers of those with backgrounds in linguistics as [linguists] have the skills required for product development and customer service in the sector”.

Then there are the valuable skills that a language degree inculcates over and above the specific content taught. That is why Prince, from the Australian Consortium for In-Country Indonesian Studies, believes that the ability of AI to translate a document does not significantly diminish the value of language degrees – “at least, no more so than ChatGPT’s ability to produce a convincing undergraduate philosophy essay obviates the value of students’ studying philosophy. The output – the essay – is beside the point. It’s the process of learning, the new patterns and habits of thought cultivated in researching and writing the essay – or learning a language – that are why, ideally, a student is paying to be at university.”

Indeed, by embracing rather than resisting technological advances, Brecht thinks language degrees could become all the more engaging and professionally valuable. US academia, he insists, is on the cusp of using AI to do “amazing things” in pedagogy but is held back by senior faculty’s attachment to traditional methods.

“Basically, it’s the language education profession itself that’s stuck in a rut, particularly in higher education,” he says. “What is discouraging is that you see all the promise [of AI], but you see all the obstacles [to adopting it] as well. We’re still operating with people who don’t see all the promise.”