‘I do much of my reading incidentally, via Twitter, while doing other things like cooking dinner’

Not long into my academic career, I took a non-fiction writing course. The instructor had published two highly acclaimed books. “To be a really good writer, you need to read – and read well,” she said. It was self-evident, and yet I immediately bristled.

“I work full-time, I have two children under four, and my partner works long hours in another city. Some days I don’t even manage to have a shower. I’m not reading much,” I said.

She looked confused. “But aren’t you an academic?”

Long-time academics will tell you that reading was once a big part of the job. In a 2017 article “In Praise of Not Not Reading”, published in The Point, Sheila Liming, assistant professor of English at the University of North Dakota, summed up the problem like this: “Our universities, like the larger culture that supports and depends upon them, do not have the structural wherewithal to recognize the work of reading as work.” Academics are now accountable for what they produce, not what they consume – and what they produce must have a dollar value.

Very few academics have time to read during teaching semesters. Pre-children, I waited until teaching finished before lining up the must-read new publications in my field. To avoid meetings and email “emergencies” during this time, I would take annual leave. Now I use my annual leave to care for my three children while the oldest two take their school holidays. I do much of my reading incidentally, via Twitter, while doing other things like cooking dinner.

Twitter is quick, conversational and to the point. Academics with an interest in a topic will often respond immediately to a specific comment or piece of information related to their field, creating within hours a discussion that would once have taken place over many issues of an academic journal. It can also create real academic communities. As we readily share information and links to articles or documents that might interest colleagues in our fields, we build the collegiality and research networks that are fading within walls of universities themselves.

On the other hand, academics and social media are not natural bedfellows. Our natural state is quiet contemplation, but Twitter can be like a jackhammer or a swarm of flies. It can heighten stress and enhance fatigue. Many “serious” people also note that it is full of nonsense and ignorance. But then, so is life; researchers are trained to find good information and filter out (or make research material of) the bad. Still, Twitter needs to change to accommodate the overworked and overwrought researchers who are increasingly reliant on it. The search function, for one, could improve.

Academics are all short of reading time, but we’re not all in the same boat. There’s a scale of time privilege. Early career researchers, who have the greatest need to rack up measurable outputs in a short time, experience the highest teaching loads and most acute levels of time-poverty. Primary carers like me also find that our early evenings and weekends are no longer available for reading and research. Both these groups struggle to win the research grants that buy out teaching time. If the Mad Hatter had hosted a tea party for academics, he would have explained it like this: “If you can ‘output’ enough research to pull off a grant, you can free up the time needed to do the research.”

Nothing beats deep reading time, and I still indulge in long reads during the few precious hours after the kids go to bed. But confined to such small windows of time, I have become an impatient reader. I dispose of dry, poorly written pieces that I might have found pertinent if I had somehow found time to read them between nine and five.

Academics who have the financial resources to work part-time or to take long breaks from work frequently use their unpaid time to read. And yet, while I look at them with envy, I have to ask: is there something wrong with an industry in which being able to work during unpaid hours is regarded as a privilege?

Verity Archer is a lecturer in sociology at Federation University, Australia.

‘I have given up searching databases and preprint servers. There is just too much content published’

I once asked my father (a retired surgeon) how he kept up with the medical literature. His somewhat tongue-in-cheek advice was to “only read the papers you agree with already”.

I have to admit that this approach is tempting, if not particularly scientific.

Another colleague admits to reading only papers related to the topic or experiment at hand. Again, I can sympathise; finding time in the diary is hard. But by leaving reading until you start a new project or need an introduction for your latest grant application, you run the risk of finding yourself out of touch, in danger of being scooped, or both.

There are certain ways to kill two birds with one stone when you read, such as doing it in the context of journal clubs, which help train your students, or peer reviewing and journal editing, which enhance your CV. Nonetheless, given the increasing demands on my time (and I suspect that of many others), it has become a case of fitting reading in wherever I can.

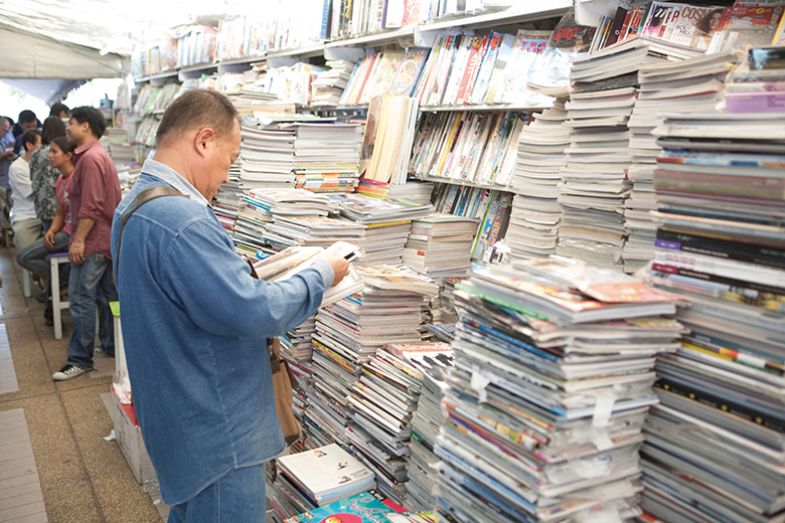

I make the effort to read (OK, skim) papers each week, but I confess that I have given up searching databases and preprint servers. There is just too much content published and no easy way to find things that are both high quality and relevant, even using keywords.

A commonly recommended tool to filter papers is to sign up to journals’ table of contents (ToC) alerts, to get a list of their latest papers sent direct to your inbox. There are several of these that, in a typical week, I studiously ignore, or delete, or run out of time to read. But I have a few go-to journals whose home pages I make a point of checking because I know they always have interesting content. These include Analyst, Analytical Chemistry and the Journal of Chemical Education.

A related option that a colleague recently alerted me to is the American Chemical Society’s mobile app, which provides personalised, up-to-the minute access to new peer-reviewed research content via my phone (serving a similar function to journal RSS feeds). I have been trying this on my commute to work recently, and I am finding it very useful.

Also easy to access on your phone, social media is very popular with scientists as a place to connect with your community, post your latest paper and talk science. The problem is that it can be a bit self-selecting – you see only your friends’ papers – meaning that you can miss quite a lot of the interesting stuff. Twitter can also sometimes be a bit overwhelming to keep track of, especially if you follow a lot of accounts. I have found it handy to follow journals of interest, as many will tweet the “editor’s choice” paper each week. The other critical thing on Twitter is knowing the right hashtag. For me, #nmrchat, #massspec and #metabolomics will often give a list of interesting articles, which can then lead me to other relevant papers.

I have also found it beneficial to read the news-and-views articles, with Chemical & Engineering News a personal favourite. Their content is less rigorous than that of full journal articles but much broader. And if you do want the specifics of a featured paper, a link to it is usually provided.

How to choose what to read? Trite as it sounds, I am not sure there is a “best way”. Everybody is different and has unique demands on their time. It is probably a case of experimenting with the different tools available – which is, at least, something we scientists are used to.

Oliver A. H. Jones is an associate professor of chemistry at RMIT University, Melbourne.

‘Conference conversations reveal the key terms of a debate faster than trawling through all the recent literature’

Working across literary studies, philosophy and the environmental humanities makes keeping up with the academic literature virtually impossible. Fortunately, I’ve realised that keeping up with the field is easier – and often more fun.

With this is mind, I go to lots of conferences and workshops. I also run academic events myself, and these often require me to get to grips with a topic quickly in order to invite speakers and chair discussions.

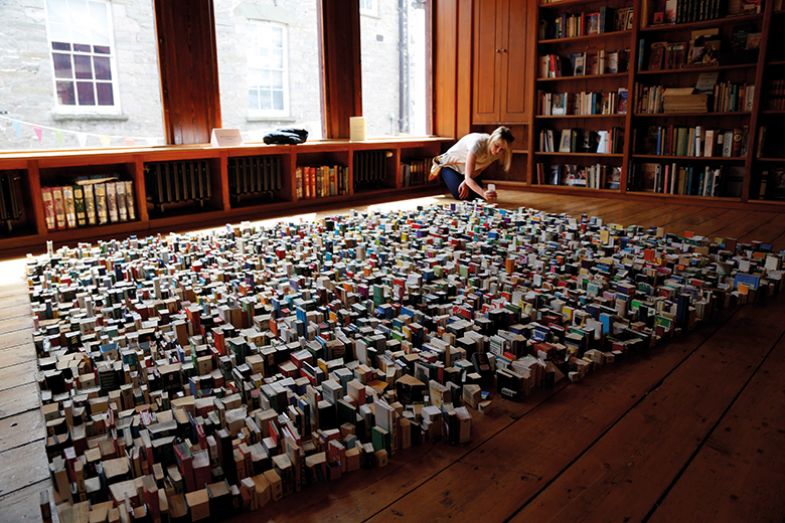

Talking is no substitute for reading, of course; but I’ve found that conference conversations reveal the key terms of a debate faster than trawling through all the recent literature – and it’s good to be reminded that thinking is a collective activity. I think of these dialogues as a kind of “pre-reading” because they are often sufficient to trigger the writing of an abstract or to gauge whether an idea has legs. In a similar way, I’ve learned to look at the big pile of unread books on my desk not as an accusation of work not done but rather as an indication of work started: evidence of growing knowledge in an area with which I’m beginning to get to grips.

Pre-reading eventually leads to actual reading. For me, this happens in bursts, when I’m writing a proposal or a paper or designing a new course to teach. I’m pretty old school about it: I hole up in the British Library for a few days and order absolutely everything on a topic, or I sit at home and tackle my pile of purchases, inspired by conferences, my PhD students and internet browsing. While this irregular pattern of reading activity has been triggered by my desire to minimise the term-time juggling, it works. Reading in clusters gives me a better overview than piecing together the field by reading a book or an article each week.

Knowing what to read is a case of supplementing old channels of information (publishers’ lists, library searches, journal subscriptions) with new ones. For some areas of my work, particularly fast-moving fields such as animal studies and post-humanism, social media has become invaluable for staying on top of new publications and current discussions. If I’m feeling out of touch, I take on more peer reviewing for publishers and write some book reviews. I also keep an eye on relevant prize shortlists. This summer, I’ve been downloading some of the listed texts for the Booker and the Wainwright prizes on to my Kindle and using them as holiday reading. I’m lucky that, even when it’s part of my research, reading contemporary fiction and nature writing still feels like fun.

The impossibility of comprehensiveness in interdisciplinary reading allows me to be a bit more exploratory in my choices than I might otherwise be, but the anxiety that my PhD examiners would produce a crucial book or article that I’d missed has never quite left me. Once I’ve started reading, I still have to fight the urge to continue until I’ve read absolutely everything.

The real challenge, however, is not so much to keep up with new publications as to address the bigger gaps in my reading that research exposes. Sometimes this is paralysing: How can I do philosophy without reading the Greeks in Greek? How can I write about nature without a complete understanding of each of the German Romanticists?

To placate this inner enforcer of the canon, I like to have some slow, historical reading on the go – or at least in the pile!

Danielle Sands is lecturer in comparative literature and thought and director of graduate studies in the department of modern languages, literatures and cultures at Royal Holloway, University of London.

‘The only time I feel vaguely up to date is preceding a grant deadline or paper submission, when I binge-read anything new’

“Ha ha ha!”

My guffaws rang out across a hundred-mile radius when I opened the email from Times Higher Education inviting me to advise my fellow academics on how to stay on top of the academic literature.

My honest response is that I don’t keep on top of it. Keeping up to date is obviously a highly variable task depending on your particular discipline and niche within it. Yet however specialist your area, I suspect there’s an almost infinite selection of mind-expanding, ideas-generating, methods-refining literature out there that no single individual could ever read in its entirety. Knowing where to draw the line is extremely hard.

The only time I feel vaguely up to date is in the days preceding a grant deadline or paper submission, when I binge-read anything new that is pertinent and refresh my memory of the old favourites. Not that I always get the credit I deserve: I was once horrified to be accused by a grant reviewer of not being “au fait with current findings” and of failing to have noticed that the chemical structure I proposed to solve had already been published.

Frantically, I searched the structure databases and sent urgent emails to collaborators, but I found no sign of it. Nevertheless, the reviewer’s comment still cast me into days of self-doubt, especially given the negligence to which I have already confessed. Worse, I had no right of reply – so, needless to say, I didn’t get the grant, despite high scores from the other reviewers. The molecular structure remains unsolved.

I also have regular mini heart attacks about being scooped when opening keyword alerts in the PubMed biomedical database. Solving macromolecular structures is painstaking and laborious, and while it can be validating to reach the same conclusion as someone else, particularly if you used different methods to get there, it is near impossible to get your structure published anywhere with official “impact” if somebody has beaten you to it.

Most of the time, though, the PubMed alerts don’t convey bad news. Sometimes they even deliver a rare boost to the ego if someone has cited my work – or a stab of indignation if they haven’t bothered. The alerts also have the useful side-effect of provoking a spate of scientific reading. I never remove an alert even when my practical interest in the subject lapses so that I’m still roughly aware of the state of things if it comes around again, as it occasionally does.

But am I on top of the literature? No. I could claim that there are too many other demands on my time, but the fact is that I have a 40-minute commute, usually seated, at the beginning and end of each day. That would be a good opportunity to attack the scientific literature, but, unless I’m in one of my binge periods, I read novels instead.

Fiction, to me, is like mindfulness or exercise to other people: it keeps me sane. And sanity is the single most valuable attribute for handling a diverse and extensive workload alongside caring for young children.

In a summer that has seen yet another social media flare-up in the working hours v productivity debate, I am more convinced than ever of the value of self-care. You should also take the time to cuddle your children, partners and pets as much as they will tolerate. Life’s rich tapestry might be underpinned by science, but it’s healthy to experience it from a variety of angles.

Rivka Isaacson is reader in chemical biology at King’s College London.

‘I make a conscious effort to step back from the brink and substitute pleasure for pressure’

Let’s face it, there’s never enough time to read. No matter how hard we try, we can’t possibly keep up with the newest scholarship in our own fields, much less with all the interesting research being published in other disciplines. It’s tempting to succumb to informational impostor syndrome: staggering under the emotional burden imposed by all those unread books and articles, we become convinced that everyone else is somehow managing better than we are.

But information overload is hardly a new dilemma; nor is it unique to 21st-century academe. As historian Ann Blair points out in her 2010 book Too Much to Know: Managing Scholarly Information before the Modern Age, scholars have been complaining at least since the invention of the printing press about having “too much to read”.

Lately, whenever I feel in danger of free-falling into a bottomless pit of references, I make a conscious effort to step back from the brink and substitute pleasure for pressure. The following “three Rs” might not work for everyone, but academics in most disciplines should be able to find ways of adapting them to their own circumstances.

The first is reframe. Sometimes all we need to do is change the lens through which we view our academic workload. In his book The Happiness Advantage, psychologist Shawn Achor recalls how he reframed a stress-inducing, deadline-driven literature review by reminding himself how much he loves learning about new ideas and research findings: “I thought about how I was defining the task mentally (menial labor) and consciously changed it (to reading for enrichment). I also changed the language I used to describe the activity to other people. After telling a few friends I was at Starbucks reading for pleasure, I started to realize that in fact I was.”

The second of the three Rs is retreat. Twice a year, Microsoft founder Bill Gates packs up a stack of books and papers and sequesters himself in a remote cottage for a week of uninterrupted reading, writing and thinking. Gates’ famous “think weeks” are what Cal Newport, author of Deep Work: Rules for Success in a Distracted World, calls a “grand gesture”: an allocation of resources that announces both to the world and to ourselves just how much we need and value our thinking time. Writing retreats are a long-established academic tradition. So why not organise a dedicated “reading week” instead, whether alone or in the company of colleagues?

Finally, reupholster. A colleague of mine keeps a comfortable “reading chair” in her office; even when she’s busy meeting with students, answering emails or pushing administrative documents around her desk, that beautifully upholstered armchair sits in the corner and gently reminds her not to neglect the pleasures of reading. She reserves her reading chair exclusively for the perusal of hard-copy books and journal articles, which are kinder on her eyes than digital screens and invite the colourful kinetic experience of highlighting key phrases and scribbling marginal comments. Sinking into the chair towards the end of the day feels like snatching a stolen moment of delight rather than succumbing to the nagging pressures of productivity.

Each of these solutions involves physical displacement (whether to a cafe, a cabin or just a different chair) as well as emotional displacement (from pressure to pleasure, from “busy” to relaxed). The glare of screens is replaced by the softer glow of white paper, and the burden of keeping up melts into the balm of slowing down.

Helen Sword is professor and director of the Centre for Learning and Research in Higher Education at the University of Auckland and is author of Air & Light & Time & Space: How Successful Academics Write (2017).

‘What we read, how we read it and, crucially, what we recommend have an impact on others’

The accelerating pace of scientific advances and the rapid inflation in the publication universe pose daunting challenges to anyone who wishes to remain informed about the latest findings and hypotheses. Although there are many possible approaches, it might be valuable to examine this problem in the particular context of the opportunities and costs of technological innovation.

Automated individual search protocols now make it possible for scientists to restrict their reading to articles that are “relevant” to their next grant proposal or ones that are potentially useful as references for citation. This approach is enticingly easy, but it has several flaws.

First, the development of an authentic capacity for keeping abreast of the latest literature is an excellent manifestation of the mutual reinforcement of teaching and conducting thoughtful research. Assuming that a course is not merely introductory, it is essential for the lecturer to evaluate and incorporate the latest significant findings in the field. An active researcher will find that much easier – provided that their search terms for scanning the literature do not restrict their attention to experimental approaches and topics related to immediate laboratory objectives. Instructors who incorporate literature-based projects into their syllabi can also further enhance their knowledge of the wider field via the efforts of their students.

Narrow reading also limits scientists’ ability to write good review articles – which amounts to a lost opportunity for both them and their readers. Many contemporary review articles are merely a concatenation of the abstracts of articles extracted from the literature with a set of search terms. The benefits of reading and writing such articles are quite limited; their main function is to supply citations for those too indolent to examine the primary literature.

However, done properly, review articles provide a comprehensive overview of a field, supply a critical perspective on the literature, synthesise the existing data into a model, and propose testable hypotheses and avenues of future investigation. Crafting such an article forces the writer to read broadly and deeply, and is a gift to readers struggling to stay afloat in the sea of articles, deluged with references to research articles in emails from journals and scientific societies, in media accounts and in social media reports.

Often I am disappointed or downright outraged by the insufficiency of the evidence provided for these marketed claims, and while my curiosity is still as susceptible as anyone’s, I believe that my experience has led me to succumb to temptation and click the links less often.

It must be recognised that maintenance of the integrity of the literature is, increasingly, a cooperative endeavour. What we read, how we read it and, crucially, what we recommend have an impact on others. We should, for example, resist the urge to promote research results that we have not personally evaluated. And we should be wary of newspaper and magazine articles by journalists who lack the training to scrutinise assertions about scientific advances and are, therefore, prone to regurgitate press releases.

The scientific literature, like science itself, has always been dynamic. Reinterpretation of the significance of earlier published results has been a constant feature of research articles. However, in the decades before the advent of the internet, a certain ossification set in, such that challenging articles by prominent researchers became considered undignified behaviour. Now, the scientific corpus has been revivified as a conversation rather than persisting as a soliloquy, and that is good.

Some of the most interesting reading consists of critiques of articles, peer review and journals. Frequently, understanding a paper’s analysis requires the reader to learn about subjects or techniques of which they would otherwise have been relatively ignorant, but this has benefits for the reader’s teaching, research and, indeed, future reading. True scientists constantly re-evaluate their sources of knowledge, and contemplate whether there may be better means for obtaining and sharing insight.

David A. Sanders is an associate professor in the department of biological sciences at Purdue University.

‘The digital humanities question encapsulates the dilemma facing academic research as a whole’

“Reading ‘more’ hardly seems to be the solution,” Franco Moretti argued at the turn of the millennium. Speaking about ways to expand the purview of comparative literature beyond its typical confinement to western Europe, the Italian literary critic called in the New Left Review for a radically different method to replace the quest for greater knowledge through more (close) reading.

This was the genesis of Moretti’s famous approach of “distant reading”, the practice of looking at larger systems of literature rather than individual texts. It would soon find effective form in the methods of computational or digital humanities, with software programs combing through thousands of texts quickly to discern broad literary and sociological patterns.

How can close and distant reading best complement each other? This question – the digital humanities question – encapsulates the dilemma facing academic research as a whole. What is at stake in the question of what to read is the social dimension of intellectual labour, now infinitely more complex in the age of digital and computational possibilities.

Entering a field of research is not that different from entering a room where a conversation is ongoing, and then adding one’s own voice to it. This requires two things: some knowledge of the history of the conversation (what did people say before you entered?), and the ability to create new knowledge (why would the inhabitants of the room listen to you?). Computers can fulfil both those criteria up to a point, but they work best at the direction of a human with their own intimate knowledge of the texts in question – and, therefore, with some insight into what it would be interesting to look for.

The reality of this struck me recently when I received an invitation from Oxford University Press to contribute to the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Literature. The invitation letter described the project as “a scholarly alternative to Wikipedia”, an attempt to create a “dynamic and constantly evolving research encyclopedia that will grow with the field”. The comparison with Wikipedia itself states the problem: is the easy research path in the age of the Google search necessarily the best one? Are the research materials that come up first when you run a simple search necessarily those most likely to be of use to you?

Staying in the conversation is a relatively straightforward process during doctoral research, where much energy is spent in the very act of entry to the room. Likewise, it is easy in the early years of professional academic life, and it continues to be easy if you stay in the same area of research. The challenges mount when you take on new research projects – and they rise in difficulty the further the projects are from your original subfield of specialisation.

But while no one can do the background reading for you, they can at least point you in the right direction. The book still plays the role of the definitive research unit in the humanities, and, for me, a key place to look beyond its specific contents is the bibliography. That represents the research trajectory of another scholar who has profitably mined the terrain before you. Following subfield-specific journals is also a very good way of staying on top of relevant research in a new field; the micro-contours are better visible there than in discipline-wide journals. For a scholar of modernist literature such as myself, that might mean choosing Modernism/Modernity over PMLA, the Publication of the Modern Language Association.

But the digital world also brings its unique social implications. After a day of presentations at an academic event, social media is always alive with posts to the effect of “Hivemind, I need recommendations on…” – with dozens of useful suggestions in response. If you don’t have time to read them all yourself, you can at least ask your computer to mine them for you!

Saikat Majumdar’s new book, a co-edited collection of essays, The Critic as Amateur, will be published in September.

‘RSS feeds have tremendous value when paired with keyword sorting’

Academics are expected somehow to have knowledge of all articles published in their field. The well-read scientist minimises wasted time and money, after all. Yet, according to an assessment by Arif Jinha, the number of peer-reviewed articles in existence had already hit 50 million by 2009. While this figure is for all disciplines, it underlines the impossibility of living up to that expectation.

Traditional scientists tend to routinely read only a handful of their favourite journals. But with the growing number of journals and the globalisation of science, valuable papers are being published in an increasingly diffuse literature landscape. RSS feeds are one option that can minimise time spent searching, and they have tremendous value when paired with keyword sorting. Most scientific feeds contain article title, author list, abstract and link to the full article, as well as the table of contents image – an underappreciated component of scientific publishing, on which journals should expend more effort to make them enticing and instructive.

The challenge remains, however, in determining which papers to read in full. As a starting point, I have success by following citation trails back to the key paradigmatic publications. Similarly, there is value in reading review articles that canvass both recent and historical efforts in a particular field. However, readers need to be wary of such papers; often their titles play a major role in their perceived value and resulting citation count because of those titles’ frequent similarity to common Google search terms that might be used by researchers interested in the field.

We should also be wary of reading only prestigious journals. It is almost certain that the most technically rigorous, comprehensive and reproducible science is published in more specialised and lower impact journals. Furthermore, not all scientists agree on what “impact” means. Some of the most talented scientists I know submit their finest work to journals in which they believe they will get the most useful visibility. This does not correlate with impact factor.

Undoubtedly, the most comprehensive approach to reading literature is to receive RSS feeds from all journals in your field, and then judiciously sort through these using keywords, authorship and citation trails. During my PhD, I would indiscriminately browse 100 to 200 articles a day using an RSS feed, but would download only a handful of full articles. This approach enabled exposure to topics outside my field and resulted in numerous new research directions (and, consequently, more publications).

In some flourishing fields, the true paradigm-shifting papers are far outnumbered by a mushrooming mass of more technical, incremental reports. However, the title is often sufficient to understand their entire content. See, for example, the field of lead halide perovskite photovoltaics. I will admit that I myself am guilty of publishing incremental work in this field – but I know that only because I kept on top of the literature using my RSS feed.

The RSS approach is certainly not without flaws – it takes time. Some practitioners find it helpful to set aside reading time, but I believe that science will immediately disobey any schedule imposed on it. Instead, the process of sourcing and reading literature should ideally be elevated to “enjoyable” and intercalated into daily activities.

In any case, I wish I had more time to read the literature amid my teaching and group administrative duties – as well as my equally important personal time.

Christopher Hendon is an assistant professor of computational materials chemistry at the University of Oregon.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Skim, skip, tweet, retreat…?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login