Browse the full list of institutions in this year’s Latin America rankings

Brazil’s State University of Campinas is the top university in Latin America, according to a Times Higher Education ranking for the region.

The institution knocks previous champion and neighbour, the University of São Paulo, down to second place in the THE Latin America University Rankings 2017, thanks to a strong performance in terms of its research influence (citations) and industry income.

However, while Brazil dominates the ranking, claiming two-fifths of places – or 32 out of 81 – only 18 of these make the top 50, down from 23 last year. Overall, 20 Brazilian universities have dropped places.

Marcelo Knobel, rector of the State University of Campinas, said that the rankings results reflected long-term improvements that the institution has made to its research strategy and knowledge transfer efforts over the past 15 years.

He said that the university has a “very selective process in hiring new faculty” and works in close collaboration with businesses on research.

However, he said that the university is struggling financially because of Brazil’s economic crisis.

“Our budget is close to what it was in 2008, but the problem is that the university grew by about 30 per cent in that same period,” he said.

“We have to restrict our investment in new buildings. It will affect the research and the functioning of the university.”

– A window on the New World

– The missing: why some high-profile institutions are absent from our rankings

– Beyond borders: lessons from the University of Guadalajara’s international overhaul

– No fees. No thanks: many people are unhappy with Chile’s plans for free HE

– The weight of tradition

An analysis of scientific research in Latin America, reported in THE last month, found that low salaries, underfunding and excessive bureaucracy were fuelling a brain drain of scholars from the region.

But some countries have improved in the ranking.

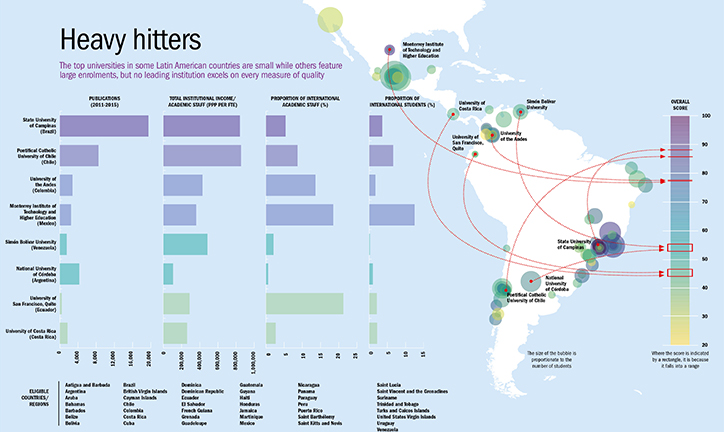

Chile has 15 universities in the top 50, up from 11 last year; Colombia has five in the top 50, up from four, and seven newcomers overall; and Argentina joins the list for the first time, claiming two spots in the table.

These three countries were recently identified by THE as part of a group of nations that were most likely to become future higher education stars.

However, Carolina Guzmán Valenzuela, researcher at the Centre for Advanced Research in Education at the University of Chile, said that it is likely that Brazil will remain the leading higher education nation in the region, given that it has the highest level of national investment in research and development.

She added that governments in the region need to provide “major investment in high-quality research projects” in the humanities and the social sciences, as well as the “hard sciences”; promote collaboration among scholars across universities within the region; and develop mechanisms to “transfer knowledge to communities so as to connect local communities with universities and research centres”.

It is “difficult to imagine that Latin American universities can compete in equal conditions with world-class universities – most of them located in the North and characterised by a single mainstream system of research”, Dr Guzmán Valenzuela said.

THE Latin America University Rankings 2017: top 10

| Latin America rank 2017 | Latin America rank 2016 | World rank 2016-17 | University | Country |

| 1 | 2 | 401–500 | State University of Campinas | Brazil |

| 2 | 1 | 251–300 | University of São Paulo | Brazil |

| 3 | 3 | 401–500 | Pontifical Catholic University of Chile | Chile |

| 4 | 4 | 501–600 | University of Chile | Chile |

| 5 | 10 | 501–600 | University of the Andes | Colombia |

| 6 | 8 | 501–600 | Monterrey Institute of Technology and Higher Education | Mexico |

| 7 | Not ranked | 601–800 | Federal University of São Paulo (UNIFESP) | Brazil |

| 8 | 5 | 601–800 | Federal University of Rio de Janeiro | Brazil |

| 9 | 6 | 601–800 | Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio) | Brazil |

| 10 | 9 | 501–600 | National Autonomous University of Mexico | Mexico |

Browse the full list of the top universities in Latin America in 2017

In search of education’s El Dorado

Expanding university participation and access have long been the focus in the region, but now quality is coming to the fore

When Times Higher Education recently published an analysis identifying seven countries that were most likely to become future higher education stars, three of the nations picked out were in Latin America.

Argentina, Chile and Colombia all featured in the new group named the “TACTICS”, based on research conducted in partnership with the UCL Institute of Education’s Centre for Global Higher Education.

The study found that Argentina and Chile both had a very high gross tertiary enrolment ratio – the proportion of university-aged students enrolled in higher education – at 80 per cent and 87 per cent, respectively, as well as a high level of research quality.

As for Chile, it ranks better than even the UK when it comes to the number of 15- to 19-year-olds in the country per university in the latest THE World University Rankings.

Meanwhile, Colombia’s research publication output has grown by 49 per cent since 2011.

The THE Latin America University Rankings 2017 lend weight to this picture of higher education systems growing in strength. All three countries have made strides in the table this year.

Although the expansion of the list to include 31 additional institutions accounts for some of the movement in the table and means that direct year-on-year comparisons come with a major caveat, clear insights can nevertheless be drawn from the data.

View this year’s Latin America Rankings methodology in full

Download a copy of the Latin America University Rankings 2017 digital supplement

Chile now has 15 universities in the top 50, up from 11 last year, as well as two more in the lower ranks.

The Pontifical Catholic University of Valparaíso has made good progress, jumping from the 26-30 band to joint 20th place, a gain driven by a large rise in its reputation for teaching.

Colombia has 11 representatives among the 81 institutions in the rankings, seven of which are newcomers. Five of these make the top 50, up from four last year.

And Argentina, along with Ecuador, joins the list for the first time this year, with the National University of Córdoba featuring in the 26-30 band and Austral University making the 61-70 cohort.

The gains for these countries occur as other nations lose ground.

Brazil still dominates the region’s higher education landscape, claiming 32 places in the table – two-fifths of the total. However, only 18 of these make the top 50, a slip from 23 last year. Overall, 20 Brazilian universities have dropped places.

The rankings give the State University of Campinas reason to celebrate: it has swapped places with the nation’s flagship and its local rival, the University of São Paulo, to claim first place. This is thanks to greatly improved scores for citations and industry income.

Mexico’s performance has also diminished. Of its 13 representative institutions, six make the top 50, down from eight last year.

Meanwhile Costa Rica’s sole representative, the University of Costa Rica, has plummeted from the 26-30 band to 41-45 despite having performed as well as or better than it did last year on most measures, showing the impact of increased competition in the table.

This ranking is published as higher education is developing rapidly across the Latin American region.

The proportion of 18- to 24-year-olds across Latin America and the Caribbean who are enrolled in higher education has almost doubled in the past decade, rising from 21 per cent in 2000 to 40 per cent in 2010, according to a recent report from the World Bank.

And although unequal access still abounds, there has been some progress in this area. On average, the poorest 50 per cent of the region’s population accounted for only 16 per cent of higher education students in 2000, but that figure had risen to about 25 per cent in 2013, finds the study At a Crossroads: Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Browse Times Higher Education’s university rankings portfolio

Another recent trend is the huge growth of the private sector. According to the World Bank, about a quarter of the universities in Latin America and the Caribbean that are operating today opened between 2000 and 2013, and many of them were private institutions. In that period, the share of private universities climbed from 43 per cent to 50 per cent. This may help to explain the increase in the number of private universities making the ranking this year.

All this progress is certainly to be welcomed, but the region will need to overcome some great challenges before it is in a position to compete globally.

The World Bank research also finds that only half of university students graduate on time (based on the number of 25- to 29-year-olds still to gain a degree) and that improving the quality of higher education is still a big hurdle.

According to María Marta Ferreyra, senior economist for Latin America and the Caribbean at the World Bank and lead author of the report, the primary reason for the low graduation rates across the region is poor academic preparation. She also points out that students at non-selective institutions or on short programmes of two or three years are more likely to drop out than those on more traditional, more demanding courses.

Another problem is that many universities are “not ready to deal with” the new influx of students, who in many cases come from low-income backgrounds and require more support than traditional cohorts. What’s more, courses at many institutions “don’t connect very well with the marketplace, so students have a hard time seeing the applicability of what they are learning,” she says.

In Latin America, many degree programmes tend to be long – requiring up to six years of study – and inflexible about allowing students to change their subject major, both of which constitute additional barriers to progress, Ferreyra says.

She suggests that universities should be given incentives through funding and regulation to improve student outcomes, arguing that this will allow governments to better direct and target money for higher education during a period of “serious fiscal constraints”.

Search our database for the latest global university jobs

“If suddenly [universities] have a requirement to report how each of their programmes is doing in the market, that will by itself give them an incentive to do better. If I ask every university to tell me how graduates of every programme are doing salary-wise or from the point of view of graduation rates, suddenly they’re going to take the issue of quality more seriously,” she says.

“We also want to know the value added [by a university education]. In other words, given the level of academic preparation of the kids who come in, how far can you take them afterwards, how much value do you add?”

She points out that Argentina and Uruguay have traditionally had high enrolment rates but have in recent years not been as focused on implementing new policies to improve and advance higher education, while Colombia, Peru, Chile and Ecuador have been “very active” in terms of development.

“For instance, Colombia, Chile and Peru have undertaken very ambitious efforts in terms of gathering information” on student outcomes and making it available to the public, she says.

The lack of internationalisation activities at Latin America’s universities is also a common criticism of the region.

Ferreyra says that universities should “rethink the design of their programmes” to enable them to “mesh better” with degrees in other countries, noting that courses in Latin America tend to last five or six years, compared with four years in the US and three in the UK.

Pablo Navas Sanz de Santamaría, rector of Colombia’s University of the Andes, which is ranked sixth when measured on the international outlook indicator alone, adds that “strong and focused cooperation with international partners will be key in our future development”.

However, the data in these rankings show that several universities’ scores in this area have declined. The five institutions with the highest scores for internationalisation – which takes into account an institution’s proportion of international students, staff and research – have lower scores on this measure than they did last year.

Many of the universities with the weakest international outlooks have also diminished in this area.

But when it comes to concerns about the standard of higher education in the region, Navas is optimistic. He says that universities in Latin America now recognise that “quality is a top priority”.

“From Chile to Mexico, I would say this is a reality. We are very aware that we went through an important period of increasing accessibility, but now quality is the name of the game,” he says.