View the full list of the best universities in Europe 2017

One of the most significant developments in the global higher education sector in recent years has been the remarkable rise in student mobility.

Across the world, 5 million individuals left their home countries to study abroad in 2014, more than triple the number in 1990 and double the figure from 2000, according to latest statistics from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.

The OECD predicts that this figure will climb to a staggering 8 million by 2025.

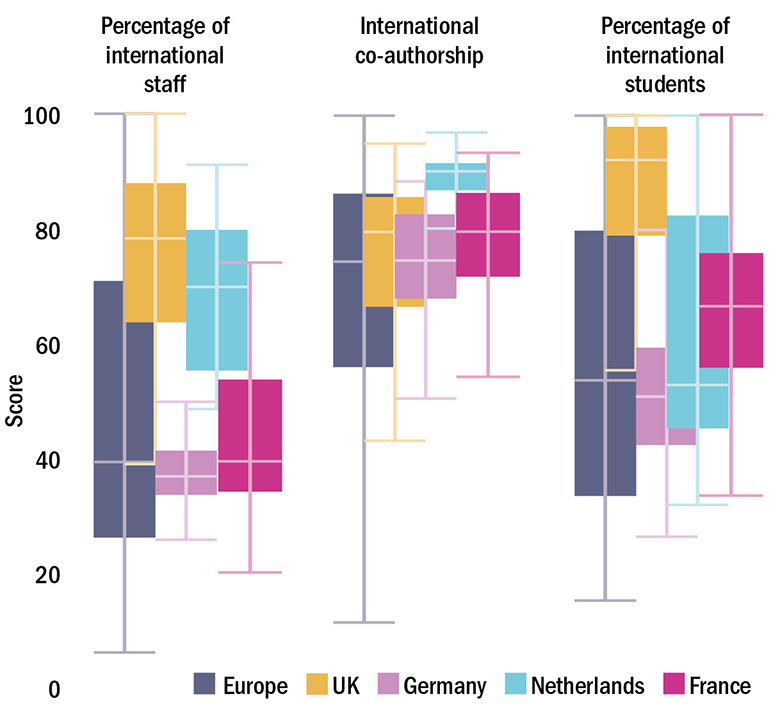

To judge by the data underlying the Times Higher Education World University Rankings, the UK is arguably Europe’s leading nation when it comes to internationalisation: almost all of its ranked institutions appear in the top 25 per cent of universities with the greatest number of overseas students (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: European countries compared on internationalisation

This result is particularly impressive given that the country has more representatives in this Europe Ranking, 91 universities, than any other nation.

Its institutions also excel in attracting international academics and publishing research with international co-authors.

Another player with a strong international profile is the Netherlands. While its universities achieve high scores on all three metrics related to internationalisation in the rankings, their main asset is international co-authorship, a fruit perhaps of the country’s research success.

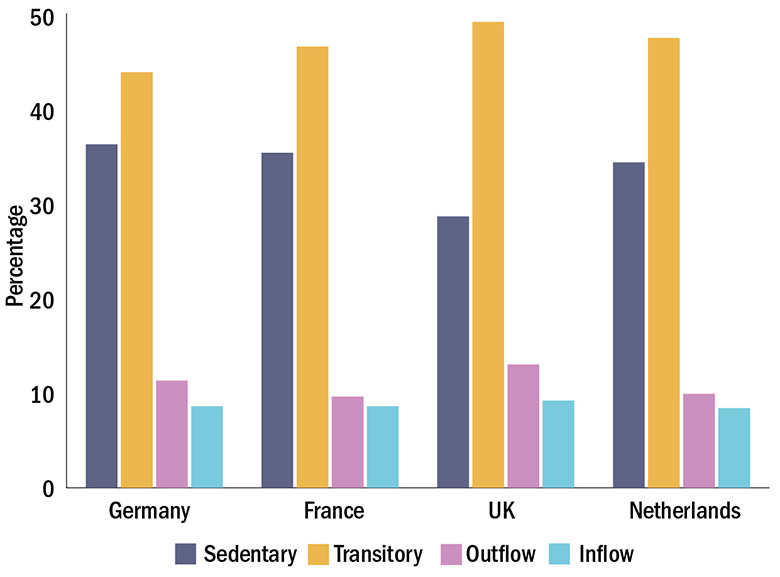

Although the number of active researchers in the Netherlands was less than half that in France between 1996 and 2015 (about 100,000 versus 238,000), their performance is similar when it comes to the mobility of their researchers. In both nations, 47 per cent of researchers published with affiliations outside their home countries during this period, according to Elsevier’s SciVal tool. This compares with 49 per cent of UK academics and 44 per cent of scholars in Germany (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2: Mobility of researchers in European countries compared

Meanwhile, 8 per cent of researchers in the Netherlands had worked elsewhere for at least two years before moving to the country, a proportion that is slightly lower than that of the other three powerhouses, while 10 per cent are based abroad after working in the Netherlands for at least two years.

Hans Vossensteyn, director of the Centre for Higher Education Policy at the University of Twente, says that the country’s strong publishing culture, the high level of mobility among Dutch scientists and the view that English is the standard research publishing language are among the key reasons why it excels in this area.

There are also several key factors that make it so successful in attracting international students, he says.

“Many study programmes are in English, both at bachelor’s and master’s level; the quality and reputation of Dutch universities is relatively good; and tuition fees, [although considered] substantial for Europe, are reasonable globally” at between €8,750 and €14,000 (£7,400 and £11,800) annually for non-European Union students, Vossensteyn says.

Figures revealed by the Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant last year found that 60 per cent of courses at Dutch research-intensive universities are taught in English, and the proportion rises to 70 per cent when only master’s degrees are counted.

Vossensteyn highlights one feature that perhaps sets Dutch universities apart from their counterparts in the UK in terms of their international appeal: the Netherlands “as a country of destination appears to be attractive” and is “overall foreigner-friendly”.

Karl Dittrich is president of VSNU (Vereniging van Universiteiten), an association of 14 research universities in the Netherlands, 13 of which feature in the THE World University Rankings.

He says that Dutch academia “has for a long time been very internationally oriented, because a country of our size could not isolate itself from the advancements in science around us” – a factor that could also explain the UK’s similar strengths.

“I believe that the main advantage of the strong research landscape in a rather small country is the cooperation that it fosters between researchers and research groups, both nationally and internationally,” he adds.

But despite the strong figures for the country, Vossensteyn says that within the Netherlands there is an “impression we are not doing so well in internationalisation as we maybe could”.

“Relatively few [Dutch] students go abroad, compared to our ambitions,” he explains.

Just across the country’s eastern border, Germany has the opposite problem.

The country is one of the world’s leading nations when it comes to young people studying abroad – according to Unesco data it is number one in Europe for student emigration and fourth in the world (behind China, India and South Korea); however, it is relatively weak compared with Europe’s other university powerhouses when it comes to attracting students from other nations.

Indeed, its university with the highest proportion of international students, according to data from the World University Rankings – the Technical University of Munich (ranked 14th in Europe and 46th overall) – falls outside the world top 150 when ranked on this measure alone.

Marijke Wahlers, head of the international department of the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK), says that one reason for Germany’s poor showing in this area could be that the country has a different “perception of what it means to be an international university” compared with other nations.

While some countries tend to focus intently on attracting degree-seeking international students, Germany also places a big emphasis on hosting overseas students on short-term programmes, she says.

Wahlers adds that the “reciprocity” of student mobility “is important for us”, and Germany looks to have a balance of outgoing and incoming students.

“We have a partnership concept in internationalisation, and we really want our students to go out and study in different places,” she says.

“My feeling would be that in the UK that is a little bit less pronounced because there are not so many UK students going out.”

Any difference in attitudes notwithstanding, Germany’s proportion of international students has been rising recently .

In 2016, the number of foreign students coming to the country rose by almost 7 per cent, having grown by nearly 8 per cent the previous year. Numbers have climbed by about 30 per cent since 2012.

Wahlers says that the lack of tuition fees for international students is one important factor for this upward trend, as are the strength of the country’s labour market and the overall quality of teaching and research in its higher education system.

But she adds that since German universities continue to offer the majority of their degrees in German, it “doesn’t seem realistic to really attract more and more international students”, at least at the bachelor’s level.

Because it is a big country that does not use English more widely across its higher education system, in contrast to highly internationalised countries such as Switzerland and the Netherlands, Germany has “lagged behind for a number of decades” when it comes to hosting international students, says Gero Federkeil, head of international rankings at the Centre for Higher Education, a German thinktank.

“As a smaller country, the Netherlands has traditionally been more open to academic exchange than large countries such as Germany, Italy and France,” he explains.

But things have been changing in the past decade, he believes.

“[The use of the] English language has become more prominent in teaching in Germany, and now about 10 to 12 per cent of all students enrolled in Germany are coming from abroad or have an immigration background,” he says, adding that he expects the number of English language master’s courses in the country to increase.

However, there is another aspect in which the Netherlands trumps Germany, which makes it more appealing to international students, Federkeil says: Dutch universities have a “strong focus on teaching”.

“This is a reason why many German students go to the Netherlands: they know that their universities have a focus on teaching and are more student-centred than German universities,” he says.

Interestingly, while the largest share of international students in the UK, France and Germany come from China, most foreign students in the Netherlands (34 per cent) come from Germany, according to Unesco data. The next largest group, at just 6.7 per cent, comes from China.

Like Germany, France is weaker than several of its neighbouring countries on internationalisation and is held back by its proportion of overseas students, according to THE World University Rankings data.

However, when considering overall numbers rather than percentages, France is fourth in the world and second in Europe in terms of incoming international students, Unesco data show, suggesting that the country suffers on some measures because of its large size.

And last year, École Polytechnique, one of France’s prestigious grandes écoles, announced the creation of five postgraduate degrees and one bachelor’s degree programme in the English language, suggesting that the country’s universities are working harder to attract students from abroad.

France, Germany and the Netherlands could also all be well placed to benefit from an influx of EU students who might be put off from studying in the UK after Brexit.

Wahlers agrees that Germany could gain from the climate in the UK, noting that of late “it seems like there’s worldwide brain circulation triggered by political developments”.

However, she goes on, she does not envisage German universities “aggressively” targeting students and academics who are from the UK or the US or who may have been considering those countries for study or work.

“We want Germany to be an attractive destination for research and study, and we’re working hard on continuously improving. But we really don’t want to capitalise on developments elsewhere and say, ‘Look at what they are doing, change your mind and come to Germany.’ That wouldn’t be a good policy, I think,” she says.

“For us, the UK is an important partner and, in the long term, we depend on our cooperation with our UK partners.”

Results in full: the best universities in Europe

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view