Browse the 350+ list of institutions in this year’s rankings

The National University of Singapore is Asia’s top university for the third year in a row, according to Times Higher Education’s annual rankings of the region.

Singapore’s flagship institution holds on to the number one spot in the THE Asia University Rankings 2018 after improving its teaching and research environments, achieving a higher citation impact and securing higher levels of industry income.

Meanwhile, Tsinghua University has overtaken Peking University to become the top Chinese institution in the table for the first time in the rankings’ six-year history. Tsinghua has a much stronger publication output than Peking and increased its research income at a faster rate than its Beijing rival.

Overall, China has 63 universities in the rankings, many of which have made progress this year, including several of its lower-ranked institutions.

– China, lodestar and exemplar

– Search for university jobs across Asia

– NTU Singapore: the small wonder with big ambition

However, Japan is once again the most-represented nation in the list, boasting 89 universities.

There is also success for Hong Kong, which has three universities in the top 10, more than any other territory, and six universities in the top 60.

In Southeast Asia, Malaysia’s flagship institution, the University of Malaya, joins the top 50 for the first time, and Indonesia has doubled its representation, claiming four spaces in the table, up from two last year.

– The five nations trying to compete with China

– How SUSTech weaves a better world

– Listen to our podcast about the results

But most of Thailand’s 10 institutions have fallen down the table as the country grapples with an ageing population and oversupply of higher education. Taiwan has also suffered declines for these reasons.

Other nations are feeling the competition in the world’s largest continent. While India, Pakistan, South Korea and Turkey have all increased their overall representation, several of their universities have fallen down the list.

This year’s table ranks just over 350 universities, up from about 300 last year. These universities come from 25 countries/regions.

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

Asia University Rankings 2018: the top 10

| Asia University Ranking 2018 | Asia University Ranking 2017 | Position in World University Rankings 2018 | Institution | Country/region |

| 1 | 1 | =22 | National University of Singapore | Singapore |

| 2 | 3 | 30 | Tsinghua University | China |

| 3 | 2 | =27 | Peking University | China |

| 4 | 5 | 40 | University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong |

| =5 | 6 | 44 | Hong Kong University of Science and Technology | Hong Kong |

| =5 | 4 | 52 | Nanyang Technological University | Singapore |

| 7 | 11 | 58 | Chinese University of Hong Kong | Hong Kong |

| 8 | 7 | 46 | The University of Tokyo | Japan |

| 9 | 9 | =74 | Seoul National University | South Korea |

| 10 | 8 | =95 | Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) | South Korea |

Browse the full list of institutions in this year’s rankings

Visitors look at a bronze sculpture at Tsinghua in Beijing, China

The stars, near and distant

China is putting its financial muscle behind its universities to develop them into international powerhouses – and other countries are finding it increasingly hard to keep up

In September 2015, researchers made history with the first direct detection of gravitational waves – a phenomenon predicted by Albert Einstein a hundred years earlier.

The discovery led to three US scientists being awarded the 2017 Nobel Prize in Physics; the Nobel committee described the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, or “Ligo”, experiment, which detected the waves, as the “most sensitive instrument ever devised by man”.

But although just three individuals claimed the Nobel honour, more than 1,000 researchers from over 20 countries had worked on the project since its birth.

Among them was a team of five Chinese scientists from Tsinghua University, who contributed to gravitational wave data analysis using advanced computing technologies to help “purify” the signals received by the observatory.

The academics had to dampen irrelevant vibrations in the signals, an exacting task that the university says is “no easier than identifying a Morse code tapped on a wine glass at a grand party bustling with noise”.

The discovery is one of several major scientific breakthroughs in which Tsinghua has played a part in recent years.

“We have given high priority to cultivating innovative talents and strived to produce cutting-edge research achievements,” explains Li Jinliang, the dean of Tsinghua’s Office of International Exchange and Cooperation, who adds that the institution has “enacted a comprehensive set of reforms since 2012, which [has] enhanced the competitiveness of the university in the global setting”.

Scientific research is now focused on “cross-discipline research, integration of defence and civilian technologies, cutting-edge research and the commercialisation of technological advances”, he says.

At the same time, Tsinghua has remained “ahead of the curve in innovative education”, Li adds, by changing the way disciplines are categorised for undergraduate admission and “strengthening liberal education”.

And the Beijing institution has “pursued deeper international cooperation in all areas to help our students gain international perspectives and better connect China to the world”.

Given such efforts, it is perhaps no surprise that Tsinghua University has improved on all five areas measured in the Times Higher Education Asia University Rankings 2018 – teaching, research, citations, international outlook and knowledge transfer.

Thanks to its improved performance, it is now the highest-ranked university in China for the first time in the Asia rankings’ six-year history. It takes second place overall in Asia, swapping places with its local rival Peking University, which slips to third. The National University of Singapore holds on to first place in the regional rankings for the third year in a row.

Another first for the rankings is that Hong Kong is now the most-represented territory in the top 10 of the table, with three institutions: the University of Hong Kong and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology have each risen one place to fourth and joint fifth, respectively, while the Chinese University of Hong Kong joins this elite group for the first time after climbing four places to seventh. On average, the territory’s institutions achieved a significantly higher score for research reputation this year.

As a result, South Korea now has just two top 10 representatives, down from three last year, with Pohang University of Science and Technology falling two places to 12th. Also looking vulnerable is the position of the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST), with the institution having slipped from eighth place to 10th this year. Overall, the country had a weaker citation impact compared with last year.

Another change this year is a further expansion of the ranking to include more than 350 universities, up from 300 last year. All universities in the top 200 are also given a distinct rank (previously those between 100th and 200th were listed in bands) to provide greater transparency of the results.

Several nations have suffered declines this year. Among them is Thailand. While the country still has 10 universities in the rankings, seven of these have dropped places. All 10 universities received a lower score this year than they did last year for the research income per academic staff metric on average.

“The quality of higher education in Thailand is getting worse year by year,” says Arnond Sakworawich, professor at the National Institute of Development Administration, a public graduate university in the country.

He attributes part of the blame for this decline to the selection and admission procedure, which he says “no longer works the way it used to” because of the country’s shrinking youth population.

Although Thailand’s higher education sector has about 140,000 available undergraduate places each year, the number of students applying for these is just 65,000 annually, Sakworawich explains.

Some universities are so desperate to recruit students that they are providing iPads for new recruits or giving tuition fee discounts to students who persuade a friend to enrol, he adds.

“Competition to get into university in Thailand right now is getting close to zero. With low quality of input, how can universities produce high-quality graduates? Thai universities right now compete on marketing strategy to lure students rather than [on the] quality of education,” he says.

Another issue bedevilling higher education in the country, argues Sakworawich, is the fact that Thais generally value a degree in and of itself and care much less about the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, meaning that many graduates lack the skills needed for graduate-level jobs. This attitude also makes the study of demanding subjects such as science, technology and mathematics, as well as vocational education, unpopular in Thailand.

“Hence, higher education in Thailand produces unwanted graduates and mismatches labour demand,” Sakworawich says.

The picture is similarly bleak when it comes to research, and Thai universities also “use obsolete pedagogy”, Sakworawich says, noting that the Office of Higher Education Commission has never succeeded in its attempts to implement a quality assurance system.

Rattana Lao is a senior consultant at the Kenan Institute Asia, which aims to address social and economic development challenges in the region, and author of A Critical Study of Thailand’s Higher Education Reforms: The Culture of Borrowing, published in 2015.

She says that Thai higher education has become increasingly decentralised over the past 20 years, with public institutions undergoing “intense administrative transformation” to become autonomous universities. A downside is that this has led to over-expansion as universities have been forced to find more income on their own, she says.

“There is an incentive, if not a necessity, for universities to open new programmes and short courses that promote a commercialisation purpose rather than academic excellence,” Lao says.

And although the Thai government proclaims the importance of research, it has not backed this up with strong financial research commitments, she adds.

The structure of research funding itself is also a problem, according to Lao, because compulsory regular performance reviews require academics to detail their scholarly output every six months.

Instead of concentrating on a “long-term research agenda that will yield beneficial results”, the system forces academics to “undertake short-term research” that allows them to “churn out papers quickly”, she says.

“To upgrade Thai universities, policymakers need to seriously think about long-term and structural change. So far, they focus only on coming up with the key performance indicators that [they] hope [will] change short-term behaviour,” Lao says.

Browse Times Higher Education’s portfolio of university rankings

Taiwan is another Asian representative that is having to grapple with an ageing population and an oversupply of higher education. The territory has 31 representatives in the rankings, up from 26 last year; however, its top six institutions have all fallen down the table, and several of its lower-ranked universities have dropped as well.

Dafydd Fell, director of the Centre of Taiwan Studies at Soas, University of London, says that although Taiwanese universities are increasingly looking to mainland China to fill the student number gap, low enrolment remains “a big problem”.

“There was a pretty significant expansion in the university sector in the 1990s and the initial post-2000 period. That meant there was oversupply,” he says. “Even the big national universities are struggling to run certain degrees. So some universities have already closed in the private sector, and there’s a push to merge universities.”

Although universities in Taiwan have some advantages over rivals in other nations of the region – its academic environment is “pretty liberal” in comparison with the sector in mainland China, and the quality of academics is “pretty high” – they are very focused on research and, consequently, “neglect teaching”, Fell says.

“A lot of the teaching is done in large classrooms. There are still some pretty important structural changes if they want to improve the quality of teaching,” he says.

Taiwanese institutions are also not as “internationalised” as universities in Singapore and Hong Kong, he adds.

View this year’s Asia University Rankings methodology

But less than 200km west, across the Formosa Strait, universities appear to be thriving.

Mainland China claims almost one in five places in the rankings, boasting 63 representatives overall, up from 54 last year.

Several of the country’s institutions have moved up the table this year: Nanjing University has climbed eight places to 17th, Tongji University has jumped eight places to 53rd, and Harbin Institute of Technology has leaped 15 places to 62nd, to name just a few prominent risers.

But it is not just China’s more elite universities that are registering improvements in performance; many institutions below the top 100 have upped their game as well.

Overall, China’s universities have received a large boost in their citation impact score and can boast of high levels of industry income.

In October, China released the first details of its Double First Class project (sometimes referred to as the Double World-Class project), publishing the names of 42 universities that the government will support to achieve “world-class” status. At the same time, it announced the 95 institutions that have been chosen to develop world-class courses.

Simon Marginson, director of UCL’s Centre for Global Higher Education, says that there is “every sign that funding for higher education and research in China will keep increasing”.

“The Double World-Class project is largely in continuity with the 985 Programme [which was established in 1998 to foster world-class universities], so we can assume that China sees that programme as having been successful and now wants to lift the top universities still further,” he says, adding that the project is “likely to achieve its aims in STEM research, providing the leading Chinese universities remain strongly internationalised”.

Developing international powerhouses would certainly pay dividends for China, but there are concerns about the creation of a big gulf between the elite universities and the rest of the higher education sector. Of the 42 universities singled out for a push to the top tier, eight are in Beijing and six are in Shanghai, while several others are located along China’s relatively affluent east coast.

Download a copy of the Asia University Rankings 2018 digital supplement

Ye Liu, lecturer in international development at King’s College London, says that China’s model of “subsidising elite universities and withdrawing fiscal responsibilities” for other institutions that tend to accommodate lower-income students will increase inequality in the country.

Her 2017 paper, “When choices become chances: extending Boudon’s positional theory to understand university choices in contemporary China”, highlights that the advantaged, affluent young people born in Shanghai, Beijing and Tianjin display a confidence when it comes to “estimating their respective academic performance” that is in contrast to the insecurities exhibited by their peers from provincial areas.

“The elite programme of Double First Class universities will showcase the research excellence of Chinese universities and help China to become the leader in science and technology,” Liu says.

However, she adds, the global prestige associated with world-class universities will do nothing to address issues of social inequality in the country.

Other observers, meanwhile, have raised concerns about what such state intervention might mean for institutional autonomy and what impact it might have on both domestic universities and foreign institutions operating in China.

Despite these worries, many are confident that China’s strategy to create a select group of world-class universities will succeed.

“According to recent research and reported statistics in terms of publications in science and engineering, Chinese universities have already outperformed some established higher systems in the West,” says Ka Ho Mok, vice-president and chair professor of comparative policy at Lingnan University in Hong Kong.

He adds: “Given the strong determination to assert China’s soft power on the global stage, together with strategic funding allocated to key laboratories and main universities through the Double World-Class project, I am confident that China’s influences in the intellectual and academic community will be further enhanced.”

Seasonal changes in performance

Click on infographic to view hi-res version

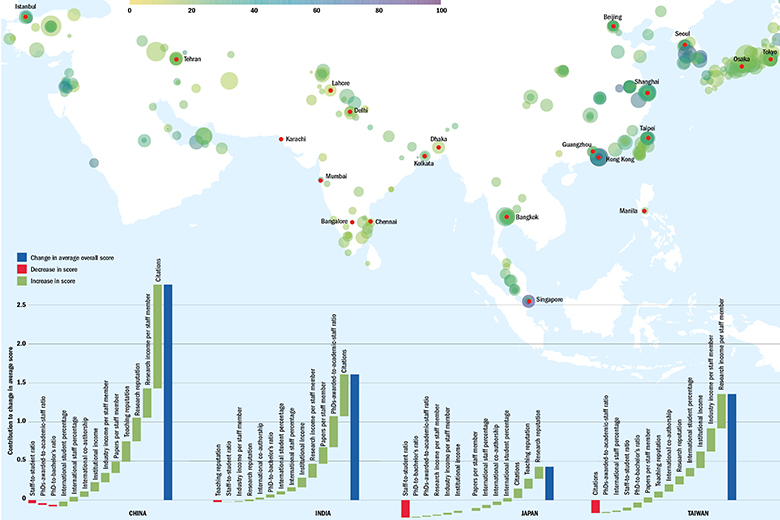

As this map shows, the location of universities in the Times Higher Education Asia University Rankings 2018 is heavily skewed towards East Asia. Although there are noticeable clusters of institutions elsewhere on the continent – and Singapore stands out in the south for its overall score – it is China, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan and Hong Kong that appear to dominate the landscape.

But delving into the data demonstrates that even within this group, and elsewhere in Asia, there is a large variation in year-on-year performance.

The five “waterfall” diagrams below, which show how a country’s overall score has changed from 2017 and how each of the rankings’ 13 metrics contributed to that, highlight how China is surging ahead thanks to a leap in citation impact score. India, too, can thank improved citation performance for a large chunk of its increase, while also picking up points in other areas such as research productivity.

Japan, on the other hand, shows a contrasting picture with continuing damage to its staff-to-student ratio – caused in large part by the country’s ageing population – undermining gains in reputation and research impact to leave it relatively static overall.

Elsewhere, Taiwan is unusual in taking a hit on citation impact but still achieving a solid improvement overall thanks to the resources being pumped into higher education. Meanwhile, in western Asia, Turkey is interesting for managing a positive outcome despite its reputation scores taking a serious knock.

Simon Baker, data editor

Watch our video of the 2018 results

后记

Print headline: The stars, near and distant