London-based universities and post-92 institutions would be hit hardest if a crackdown on UK international student visas goes ahead, analysis reveals.

The UK sector is more reliant on international student revenue now than it was the last time there were serious threats to overseas recruitment, during the prime ministership of Theresa May (2016-19). In 2020-21, tuition fees from non-European Union students were worth about £7 billion to universities, roughly 17 per cent of their total income – up from 16 per cent the year before, and 13 per cent in 2016-17.

Following the openness of Boris Johnson’s government towards international students, his successor Rishi Sunak – and in particular the home secretary, Suella Braverman – have expressed concern about the impact of education visas on overall migration figures.

But reports have suggested that any clampdown on recruitment could be targeted, potentially restricting international enrolment to “elite” universities only.

Analysis of Higher Education Statistics Agency figures indicates that institutions in the top 200 of the Times Higher Education World University Rankings draw about a fifth of their income from international students. Should ministers decide to reduce international student numbers, they could follow a pattern they set last year when they introduced a visa scheme for graduates of universities in the top 50 of major global rankings, and restrict enrolment to only that elite group.

But non-EU fees are also important for institutions outside the elite. Among post-92 universities, non-EU fees accounted for about 14 per cent of income in 2020-21, up slightly from the year before.

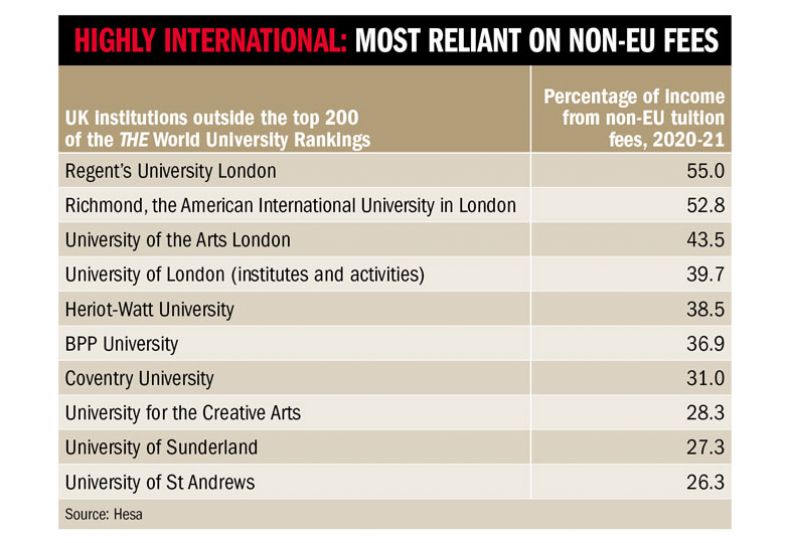

And there is significant variation in the proportion of total revenue that UK universities outside the top 200 draw from overseas recruitment. Two private institutions obtain the majority of their income from this source – Regent’s University London and Richmond, the American International University in London. Beyond these, the University of the Arts London received 43.5 per cent of its earnings from international students in 2020-21.

Other heavily exposed institutions outside the world top 200 include Heriot-Watt University (38.5 per cent of income), Coventry University (31 per cent), the University of Sunderland (27.3 per cent) and the University of St Andrews (26.3 per cent).

Institutions that rely most on international student fees

Across the 22 modern universities that form the MillionPlus group – among the institutions that could find themselves under greatest financial pressure from other income sources including domestic recruitment – international students provide 12 per cent of income.

“Any attempts by the government to massage migration figures by moving to limit international students would be wrongheaded and harmful not only to modern universities but to the UK higher education sector overall, as well as to the global standing of UK plc,” said MillionPlus chief executive Rachel Hewitt.

“Given that there is little evidence that these students overstay their visas in large numbers, and that international students are not high on the public’s list of concerns as far as immigration matters are concerned, the most straightforward solution would be to remove international students from net migration figures or at least to measure them in a more nuanced way.”

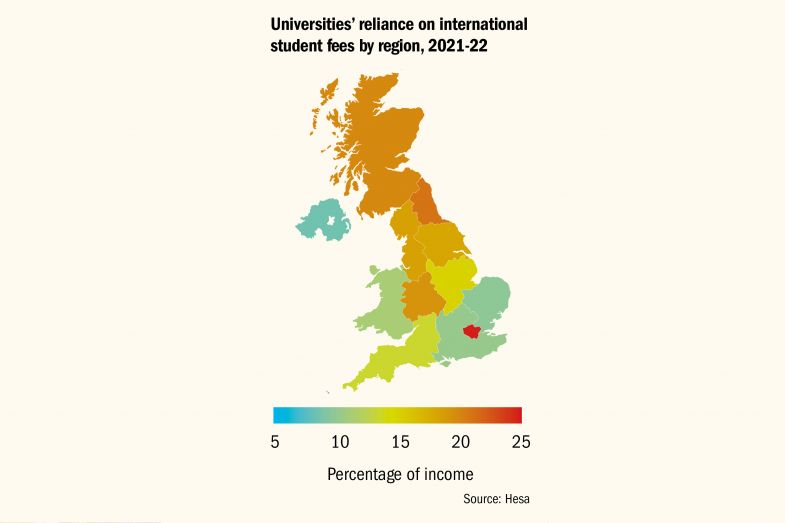

Non-EU student fees make up quarter of London universities’ income

Across all UK institutions, London universities are most reliant on the international market, drawing a quarter of their income from non-EU students.

In contrast, such students account for just 9 per cent of revenue in Northern Ireland.

The income that international students generate is essential to help universities make up the growing shortfall on the cost of teaching domestic learners, said Diana Beech, chief executive of London Higher, which represents institutions in the capital.

“Any attempt to crack down on the number of international students coming to London would have devastating consequences for both the financial sustainability of many of our world-leading institutions and the hundreds of thousands of UK workers whose livelihoods are dependent on our vibrant university communities,” she said.

The Department for Education is reported to have mounted “strong pushback” against the idea of limiting international recruitment to top-ranked universities only, and some policymakers question how feasible such a proposal would be to implement.

Many experts believe that the likeliest outcome of any policy offensive in this space would be a limit on the number of dependants who can accompany a student on their visas. These numbers have grown significantly in recent years, and Ms Braverman has raised concern about the “very high” number of family members “piggybacking” on student visas.

A recent report in The Times suggested that the home secretary has drawn up plans to address that by raising the income threshold for each additional family member.

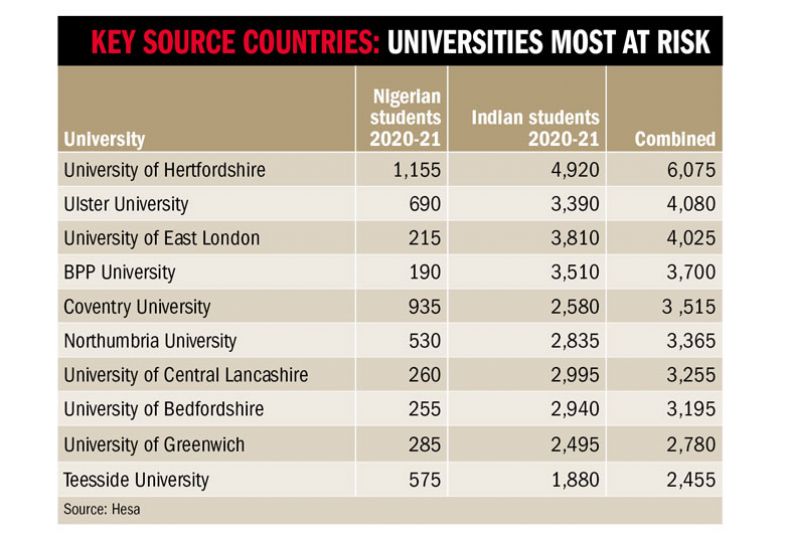

Home Office data show that 70 per cent of all dependants entering the UK on study visas in 2021-22 were from Nigeria and India. Therefore universities that rely heavily on these nations might be considered particularly at risk from any crackdown.

Universities with the most students from Nigeria and India

Of all UK institutions, the University of Hertfordshire is the most popular with both nations, accepting 1,155 students from Nigeria and 4,920 from India in 2020-21, a combined total of 6,075. This is roughly 10 times its total in 2016-17.

Ulster University and the University of East London each have combined totals in excess of 4,000.

Quintin McKellar, Hertfordshire’s vice-chancellor, said his institution would be “deeply concerned” if the government “were to enforce restrictions on overseas students”, noting that the increased recruitment was the result of the government’s stated ambition to grow and diversify overseas enrolments.

“We also need to acknowledge the significant, negative impact that reducing the number of international students would have on the UK’s higher education institutions, as well as industry and the economy overall, at a time when we really can’t afford any more knocks,” said Professor McKellar, who added that the sector should be consulted before any “rash decisions” were made.

后记

Print headline: Student visa crackdown ‘would harm whole sector’