Australia has long prided itself on being the land of the “fair go” – a place where egalitarianism, rather than class, shapes national identity. While this stereotype has been somewhat tarnished by a widening wealth gap in recent years, data from Times Higher Education suggest that the country’s universities are still ahead of the rest of the world when it comes to tackling inequality.

Three Australian institutions, led by James Cook University, top the THE University Impact Rankings table on “reduced inequalities”, which was published earlier this month and measures institutions’ research on social inequalities, their policies on discrimination and their commitment to recruiting staff and students from under-represented groups.

Metrics include the share of first-generation students, the share of international students from low-income and lower-middle-income countries as defined by the World Bank (counting only students from such countries who receive financial aid that significantly supports them), and the share of students and staff with disabilities.

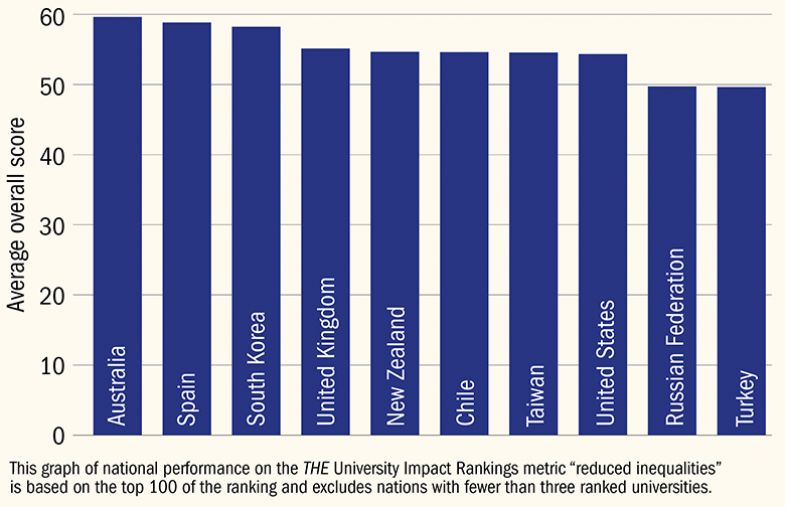

Universities in Australia received an average total score of 59.6 out of 100 in the table – higher than any other nation – coming ahead of Spain (58.9), South Korea (58.2) and the UK (55.1). The analysis was based on the top 100 of the ranking and excluded nations with fewer than three ranked universities.

Dawn Freshwater, vice-chancellor of the University of Western Australia and chair of the nation’s Group of Eight universities, said that although there were vast differences in wealth in Australia, the “rhetorical, cultural power of the idea of egalitarianism” – including a “general discomfort with anything that feels like a master-servant relationship” – plays an important part in the nation’s success in the ranking.

Australia’s “unusually inclusive electorate” – a consequence of the fact that voting in state and federal elections is compulsory – also has an influence on political discourse around inequality.

“Both major political parties, on the left and the right, have at least a verbal commitment to addressing inequality in higher education: the right places its emphasis on equality of access and opportunity for regional students; the left on socio-economic factors,” Professor Freshwater said.

Margaret Gardner, president and vice-chancellor of Monash University and chair of Universities Australia, said there have been “successive waves of federal government policy tied to funding frameworks that have caused universities to monitor performance in terms of access and participation of disadvantaged groups among students”.

Jade McKay, a research fellow at Deakin University who specialises in research on students from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds, said that the Australian government, at both federal and state levels, views the “increase in numbers of Indigenous students in higher education as a critical and essential priority”.

Australia’s location in the Asia-Pacific region and its position as a developed country surrounded by developing nations is arguably also an advantage in the ranking, given the metric on the share of students from low-income and lower-middle-income countries – many of which, including India and Indonesia, are in Asia. However, it is important to note that China is excluded, given its classification as an upper-middle-income country.

“There is no doubt that Australia benefits from being from a dynamic Asia-Pacific region,” said Dr McKay, adding that Asia is the most populous region in the world and home to “some of the most varied and complex societies in the world”.

“The region is also said to be becoming the largest producer and consumer of goods and services in the world, and Australia’s proximity is obviously of benefit from a trade [and] education perspective.”

James Cook University has strong ties to Asia. It has an international campus in Singapore as well as a wide range of partnerships “across the tropical world” and beyond, including in the Philippines, Indonesia, Central and South America, Africa, Papua New Guinea and the Pacific, according to its vice-chancellor, Sandra Harding.

The university also has “multiple programmes aimed at recruiting students from under-represented groups” and “numerous offices and officers committed to diversity, equity and human rights on campus”, she said.

“Reflecting the demographics of northern Queensland, JCU has a high proportion of students who are the first in their family to undertake higher education, as well as students from regional and remote Australia, those of a low socio-economic status, and Indigenous students,” Professor Harding added.

David Lloyd, vice-chancellor of the University of South Australia, which claims third place, said that providing access to disadvantaged groups was part of the founding mission of the institution. The 1990 act to establish the university states that it should “deliver programmes to meet the needs of Aboriginal people and the needs of groups within the community that have suffered disadvantages in education”, he said.

THE data show that 59.5 per cent of students at the institution are the first in their immediate family to attend university. Professor Lloyd said that many staff at the university, himself included, were also first-generation students, including the provost, the deputy vice-chancellor for research and innovation, the chief operating officer and the head of HR.

But Stephen Parker, research fellow in education policy and social justice at the University of Glasgow, said it was notable that the most prestigious universities in Australia either featured low down or were absent from the reduced inequalities list.

“Institutions that have higher prestige…have persistently low rates of participation from low SES [socio-economic status] students. This is broadly similar to the UK (and England in particular), where certain institutions seem to do the bulk of the heavy lifting in terms of widening participation, while the elite institutions continue without much regard for it,” he said.

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

Best at ‘reduced inequalities’

后记

Print headline: Equality is a top priority Down Under