There are three all-important issues in British higher education policy: funding, access and numbers. As a country, we have traditionally opted for a university system that is relatively expensive, relatively elite and relatively closed. To understand why, you need to know about Eton as well as Oxbridge.

Historically, England had a small university sector dominated by students from expensive public schools and selective grammar schools. Quite naturally, the sequel to Tom Brown’s Schooldays (1857), published four years afterwards, was Tom Brown at Oxford.

As recently as 50 years ago, just 6 per cent of school-leavers in England and Wales went to university, and 92 per cent of them emerged from an independent school or a grammar school. Yet three out of four school-leavers had attended other state-maintained schools, typically secondary moderns.

All this changed with the expansion of higher education, foreseen by the Robbins report of 1963. Growth was bolstered by three interrelated changes: people leaving school later; a rise in A-level entries; and the rise of comprehensive schools. Today, about four in 10 school-leavers enter higher education but just 13 per cent of all those accepted into higher education come from an independent school or one of the handful of remaining grammar schools.

Yet the university sector did not change as much as might have been expected in response. The desire to deliver higher education on a traditional model, with young people studying full-time on a residential basis, had secure roots. As higher education policy expert Guy Neave, current director of research at the Centre for Research in Higher Education Policies in Matosinhos, Portugal, wrote in 1985, “mass higher education in Britain was elite higher education written a little larger”. The desire of other institutions to emulate the expensive and residential Oxbridge model was so strong that even the polytechnics were tempted by it.

A national university system is unusual. In the US, students are encouraged to study closer to home by public universities’ practice of charging lower fees to students from their home state. About half of European Union countries offer students no support for living costs, discouraging all but the richest from leaving their local area. In vast and sparsely populated Australia, most students also study locally, so there is less need for generous maintenance support. Recent debates in Wales over the future of student finance suggest that Welsh students too might soon be discouraged from travelling to other parts of the UK for their higher education. (Currently, Welsh students pay the first £3,685 of their tuition fees, wherever they study in the UK, and the Cardiff government pays the rest.)

To understand why England has the university system it does, it is necessary to search for an underlying reason for why it became, and remains, such an outlier. It did not happen by accident.

The answer lies, I believe, in the way that upper-middle-class families educated their offspring: out of sight and out of mind. Children sent away to boarding school as young as eight are unlikely to return home (or even near to home) for undergraduate study on turning 18 because they have long ago cut their mother’s apron strings. Indeed, they are more likely to travel further afield to cement their independence. Boarding school headteachers used to say that upper-middle-class children travelled south to school and north to university. In my own case, I was sent 35 miles south to school at the age of eight and travelled 135 miles north to university aged 18.

Only a tiny number of school pupils have ever been sent away to board. Even in 1967, less than 2 per cent of the total school population were boarders. Despite the lure of Harry Potter, today there are only 541 eight-year-olds boarding in the UK, according to the latest census of independent schools – considerably less than 0.1 per cent of the age group. Yet the tiny proportion of people who went away to school in the past, either to elite public schools or selective grammar schools with boarding facilities, made up a substantial proportion of those who went to university.

This could have changed as a result of the big increase in the number of people ready for university-level study after the Second World War onwards. But the proportion of students who lived at home fell from 29 per cent to 20 per cent between 1954 and 1961. Then, the new-model universities founded in the 1960s were, in the disapproving words of Eric Robinson, an adviser to Labour education secretary Anthony Crosland, established by people seeking “to reaffirm the boarding school principle”.

The new students may not have been educated at Hogwarts or Malory Towers, but a boarding-style higher education system had been set in stone. Efforts were made over the years to change it. As education secretary in the early 1970s, Margaret Thatcher called for more students to live at home, as her daughter Carol did (before escaping to work on the other side of the world, in Australia). But little changed in practice. After all, it made sense for students to seek the best course for them, wherever that might be — especially if taxpayers were willing to pay for them to go away.

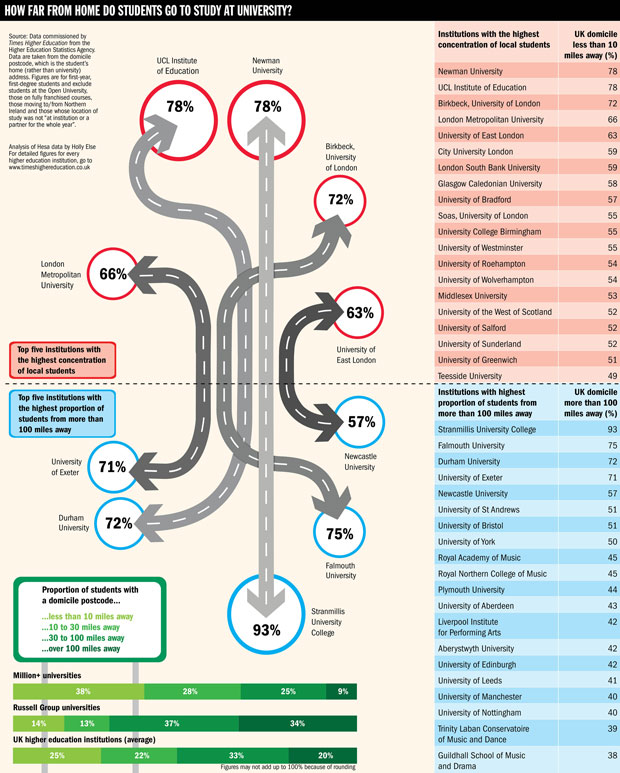

Today, UK students travel an average of 91 miles to study, according to a BBC survey, although data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (see graphics, below) show great variation between institutions. More than 70 per cent of students at the universities of Falmouth, Durham and Exeter travel more than 100 miles to be there. By contrast, less than 5 per cent of students have travelled so far to attend the University of Bedfordshire, the University of the West of Scotland and Birkbeck, University of London.

Before £9,000 tuition fees began in 2012, the insurance company LV= predicted that higher fees would persuade far more students to live at home and cause a “student exodus [that] could leave university cities ‘ghost towns’ by 2020”. But there is no evidence that this has happened. Indeed, one survey of sixth-formers by Cambridge Occupational Analysts suggests that the proportion who favour studying near their home halved between 2004 and 2013, from 15 per cent to 7 per cent. Hesa data suggest the proportion of full-time and sandwich students living in the parental home (or the home of a guardian) has been more or less static, at one in five, since 2007‑08.

So the boarding-school model remains pervasive, at least for young full-time students. Indeed, it is so dominant that some well-informed young people desperate to go to our most prestigious institutions – particularly Oxford and Cambridge – search out courses with lower numbers of applicants in preference to applying for a subject that really appeals to them closer to home. That is rational and even encouraged by the system that exists, but in many other countries it would seem absurd.

The primacy of the boarding-school model shapes the university sector in all sorts of ways. For example, it explains why there is such a rigid distinction between full-time and part-time study. A substantial system of maintenance support needs to have a clear line between those students who study intensively enough to be entitled to it and those who are studying less intensively and are assumed to have other sources of income, such as wages. That also helps explain the lack of prestige for vocational study, as maintenance support is not available for those on the vocational pathway, who are therefore incentivised to stay at home.

The overall effects are profound, and both positive and negative. On the plus side, there are clear benefits for individuals moving away from home to study, who enjoy more independence. It is adulthood more than kidulthood. In his 2014 Higher Education Policy Institute Annual Lecture, Paul Wellings, former vice-chancellor of Lancaster University and now vice-chancellor of the University of Wollongong in Australia, said: “The student experience in Australia is less coherent [than in the UK] as many students travel back to their parental home each day and make their social arrangements with existing networks, often derived from school.” The greater independence of UK undergraduates may also help explain why they typically take less time to complete their degrees than has been usual in many other countries.

Moreover, the system allows universities to play to their particular strengths rather than solely to the demands of their locality. To that extent, it explains both why we have a relatively hierarchical higher education sector and why our best-performing universities appear at the top of the global league tables.

But when each institution plays to its own strengths, it can encourage stratification and a hierarchy of institutions. There are other important downsides. First, policymakers find it harder to shape local higher education institutions according to the needs of their areas. Oxford and Cambridge have to focus on keeping up with the universities of Harvard, Yale and Stanford, rather than addressing more parochial concerns. Compare the UK with Germany, where universities, funded by the country’s 16 states, educate large numbers of local students, leaving much of the best research to be conducted in separate, non-teaching research institutes.

There are also consequences for taxpayers. The late Martin Trow, the educational sociologist, wrote long ago: “No [other] country in the world could operate a system of mass higher education at the per capita cost levels of the British universities and polytechnics.” It turned out that the UK could not afford it either. Spending per student fell from the mid 1970s onwards, maintenance loans began to displace maintenance grants in the early 1990s. Then tuition fees were reintroduced in the late 1990s – and, in England, later tripled and then tripled again. The large further cuts the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills is facing mean that a shift from maintenance grants to loans is now on the cards. Given the cost of the boarding-school model, it is no surprise that the UK has moved further and faster towards a loan-based student finance model than pretty much anywhere else in the world.

The argument can be overdone, for two reasons. First, there are plenty of British students who do not go away to study, particularly mature and part-time ones (although part-time numbers have declined sharply, especially since £9,000 fees came in). Second, it is easier than it once was for people to study locally as there has been a reduction in the number of areas that lack local higher education provision, known as “cold spots”.

But England in particular has chosen to implement policies that have a large opportunity cost. Whenever anyone argues that there should be more money for disadvantaged undergraduates or university research or further education, they should begin by asking themselves whether we have made the right decision to spend so much on encouraging full-time students to live away from home.

John Denham, Labour’s secretary of state for innovation, universities and skills between 2007 and 2009, thinks not. He is on a self-declared mission, according to his 2014 Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce lecture, “to challenge the lazy assumption that it does not matter if vast numbers of students have to leave home to study a suitable course”. He argues that we should instead “give students a real choice to study from home because it is much cheaper and is the only realistic way of bridging the gap between the maintenance system and the real costs of studying”.

It is hard to see how we move from here to there and it is not necessarily a desirable thing to do. But Denham is right to think imaginatively because spending per student will remain a key issue. Having more students, rather than fewer, makes sense because – on average – graduates enjoy all sorts of benefits, including higher earnings, and employers need graduate-level skills. Given the inevitable trade-off between the number of places and the amount of funding available for each one, however, more things may have to give to pay for them all.

One option is to accept that it is only possible up to a point to run a mass higher education system as if it is an elite one. That way, the existing system could be left alone while new models are built on top. Further education colleges and alternative providers can deliver higher education more cheaply than a full-blown, multi-faculty research-intensive university can. They provide a different type of student experience but still a very valuable one. Judging by the success of Coventry University College, an offshoot of Coventry University, this space can be occupied by traditional universities, too.

So there is a potential route for English higher education to become less expensive, less elite and less closed without losing the world-class strengths of our traditional universities. Yet the boarding school model is likely to remain popular – and more students could soon choose to study even further afield as options to study abroad grow. The big challenge is how to make more local higher education look similarly enticing.

Nick Hillman is director of the Higher Education Policy Institute.

后记

Print headline: They would walk 500 miles