What the UK’s university system needs now, entering the second quarter of the 21st century, is very much the same as the Tang dynasty needed – and introduced – in imperial China during what we would call the Dark Ages. I mean the jinshi, the system of public examinations that were used to recruit the imperial civil service.

The problem that the jinshi sought to solve was that the existing system of recruitment, based on recommendations by local notables, was wide open to nepotism and corruption. Instead, the jinshi aimed to select candidates on merit, which in this case meant knowledge and understanding of the Confucian texts. Let’s accept that what counts as merit is always going to be at least partially contested, but that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be seeking it out.

In the present day, the problem is, in a sense, grade inflation. But, more accurately, the problem is what flows from grade inflation. In my generation about 4 per cent of the population went to university and about 4 per cent of those were awarded first-class honours degrees. If you were one of those 0.16 per cent of the population you were a “high-flyer”, offered the “fast track” (specifically in public service) and the world was your oyster. Now, about half the relevant age cohort go to university, and around a third get first-class degrees. When 16 per cent of the population has a first – 100 times more than in the 1960s – it is inevitable that the system of awarding degrees cannot play the sort of role in the labour market that it used to play.

The more specific problem for universities and other employers is that if you can’t pick out high-flyers at a young age, all you can offer by way of a career route is a long and winding road that many people are going to find unattractive. Long ago, I was a (surprisingly well-remunerated) university teacher at the age of 21 and had a “tenure-track” job at 22. By the end of my career, a good student who wanted to become an academic would normally have to go through a master’s degree, a doctorate, research and/or teaching assistantships and temporary academic posts if they were ever to get a permanent academic job.

If you stop to think about what human beings have achieved intellectually before the age of 30 in recorded history, the idea that you might have to slog it out beyond that age just to get a worthwhile job is simply ridiculous. In the later years of my career, I failed time after time to persuade the better students I taught to contemplate an academic career. And all of my own children might have considered it back in the day, but eschewed it as presented.

It is worth asking what exactly are you claiming about someone when you give them a degree that includes a mark or classification. When I was first on examining boards, there was a kind of vehement orthodoxy among the generation above me that it was all about “exit velocity”. They had no interest, they said, in what an 18-year-old might have learned and then forgotten, but only in what was retained and related on graduating at 21. Thus, there was opposition to any kind of exams early in student life and to anything (such as essays) other than genuinely final exams counting for more than a tiny fraction of a degree. There were also subsidiary arguments about it being a good thing that exams were stressful. Thinking and reacting quickly under pressure: why wouldn't it be good to measure the ability to do that? As for degrees marked by your own tutor? You could not possibly be serious.

But, ultimately, all those battles were lost. There was a lapse towards a US-style system that saw a degree as something that could be banked as a set of credits. A UK degree became not so much a measure of your abilities to assemble thought at the end of your undergraduate career as a certificate of willingness to go through prescribed motions. At best, it was a certificate of competence.

I am not suggesting we could ever go back to the old system; it would be politically impossible. People going to most UK universities now pay money and have expectations. Many employers want a certificate of competence and need people who are prepared to go through prescribed motions.

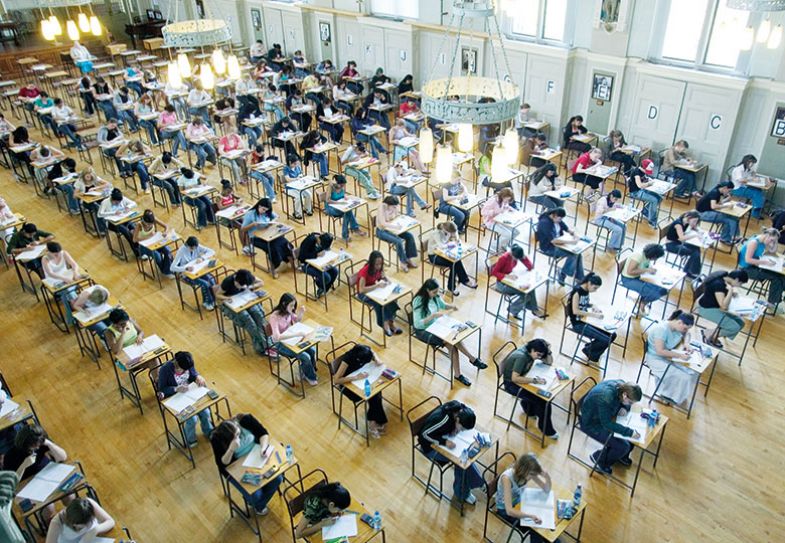

But it would be possible to complement the current system with an additional alternative of traditional exams, the results of which might be of considerable interest to certain employers, including academic employers. These would be public examinations held under traditional conditions. They would be timed, unseen and impossible to prepare for. They would measure what you know about history or physics rather than solely the content of any particular course in those subjects. They would be very much for the off-piste thinker. The resulting stress should be relished rather than mitigated. They should seek to test breadth of knowledge, but also a wide range of ways of thinking.

In some ways, they would stand to existing degrees as the old S levels did to A levels. S originally stood for “scholarship” because they were used for the award of state scholarships, but they continued as “special” papers, of particular interest to Oxford and Cambridge colleges, until 2001. I took them in the early 1960s in history and economics. While the A level might require you, for example, to show knowledge of the textbook theory of oligopoly, the S level might ask you to consider something much broader, such as the circumstances under which you would recommend protectionism to a newly independent state. (There were a lot of those at the time.)

I can muster a lot of experiences that tell me marking systems often do the opposite of rewarding broad or original thought. Actually, I go back to O level autobiographically: we did a very modern English literature syllabus – poems by Thomas Hardy, a play by Sean O’Casey and travel writing by Laurens Van der Post. I had read the books thoroughly and formed clear opinions, which I expressed in the exam. Nevertheless, I failed. By contrast, I received the highest possible mark in maths. Yet I would have considered myself better at literature than maths.

I can’t say it has rankled ever since because I honestly couldn’t have cared less even then, but it has informed my opinion about marking. A quarter of a century later, I was involved in a kind of control experiment when we decided to re-mark the papers of our exchange students from a fairly prestigious American university. Our marks diverged widely from those originally given by the students’ American tutors: we were looking for bold and clear lines of argument, while they were rewarding demonstrations of knowledge of the set texts. I was scornful; after all, in the long term, who gives a damn about whether you know what these obscure and mediocre textbooks said? Whereas the issues (urban planning and politics in the case of the papers I was marking) are important.

There are plenty of examples of the sort of exams I have in mind. The All Souls exam at the University of Oxford – where four papers can win you a seven-year fellowship – is a small but famous example. The Civil Service exam – where a candidate I knew was asked to discuss how a supermarket manager might arrange groceries within a store, a question he’d never given ordered thought to before – is perhaps the most important. Some elements of the Oxbridge admissions process are like this and, in the days when you put a lot of effort into admissions, we examined applicants for philosophy and politics on subjects they had never been taught. The A levels in those subjects were almost non-existent and other A levels were a poor guide to whether a person could think philosophically.

There is actually an amusing fictional extension in W. S. Gilbert’s libretto for Iolanthe (first produced in 1882), in which the half-fairy Strephon threatens the House of Lords that he will replace them with a chamber selected by competitive examination (I’ve heard worse ideas).

Strephon’s plan offers a key to an important part of the argument. Open, competitive examinations were intended to be – and still can be – the alternative to privilege. Their use in the universities and professions enabled a level of social mobility far higher than is now the case. Exams are of much less value if you can be precisely schooled to do well in them since the good schooling is likely to be done in the good schools. In the days when we ran our own entrance exams, we uncovered (and accepted) applicants with barely an O level, mostly “mature” students who had read and thought about philosophy and politics more than some of the well-qualified candidates were ever going to.

Of course, there are such people also in expensive schools, but there are also those who compartmentalise learning as a limited part of their lives and just learn what they are told to learn. Thus, my proposal is intended to benefit a broader category of people rather than a narrower one, although advantages will always be advantages. It goes almost without saying that the exams should be unpredictable and that those setting and marking them should have no interest in whether the results are good or bad.

So, you register online with the National Independent Board for Higher Examinations and turn up at the appointed hall with a sufficiency of pens. This is entirely voluntary and confidential. Over two days, you do two to four papers in your chosen field, which can be selected from most major academic non-vocational subjects. Who are you? Well, you might be anybody, including a foreign tourist having a shot at these famous examinations on the same trip as they take in a Shakespeare production at Stratford-upon-Avon and a Premier League game at Fulham. You might be a retired professional who never went to university but who has nurtured their love of history or literature.

But you are most likely to be a recent graduate who thought that the courses and examiners did not do you justice or that your knowledge and understanding of your subject was actually rather superior to that of some of your fellow students who were also awarded first-class degrees. Your efforts will be marked by at least two different markers – probably late-career or retired academics – who have no idea who you are and will award you a pass, a fail, a merit or a distinction. Nobody but yourself need know your result, but it can be independently verified and publicised if you wish. A pass would be a real achievement, the higher grades even more so.

I would also include – probably as a separate qualification – a general knowledge stream. As with the predecessor models, one element of this would include essays on themes that cross disciplines (try “Time”, “Risk”, “Sport”), but it would also include a fact test. A thousand questions ranging over all academic subjects in three hours, multiple choice, structured to require knowledge of several subjects. Nobody could do the lot, but it would be interesting to see what the best competitors could achieve. I am a quizzer – a winner, since you ask, of the Whitbread national pub quiz championships and second in Brain of Britain – and I get heartily sick of people who don’t know anything and don’t want to. If you don’t know, you can’t make connections and you can’t properly use the vast resources now available online.

The most common complaints I ever hear from experienced academics are connected: these are that grade inflation means that the examinations system is no longer fit for purpose and that students are no longer taught or encouraged to think for themselves. A third complaint is that many degrees are in very narrow slices and involve very particular conceptions of what constitutes “history”, “sociology” or “theology”, but I think that complaint would always have been valid in many cases.

Radical reform of existing university practice, in a world of mass and costly higher education, is not politically possible. But a complementary independent examination system looking for breadth and vision in knowledge is both possible and necessary.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick.