By now, most final-year undergraduates across the northern hemisphere have found out what their years of toil (or Xbox playing) have amounted to in terms of the degree scores that will forever adorn their CVs.

In the UK, this was historically all about the relief or despair of finding out which side of the magic boundary you fell on between upper and lower second-class honours degrees; only the former are typically regarded by employers as a “good” degree. In a few cases, it was also the moment when extra dedication was justly rewarded with a first-class degree.

But receiving a “good” honours degree is increasingly becoming a given.

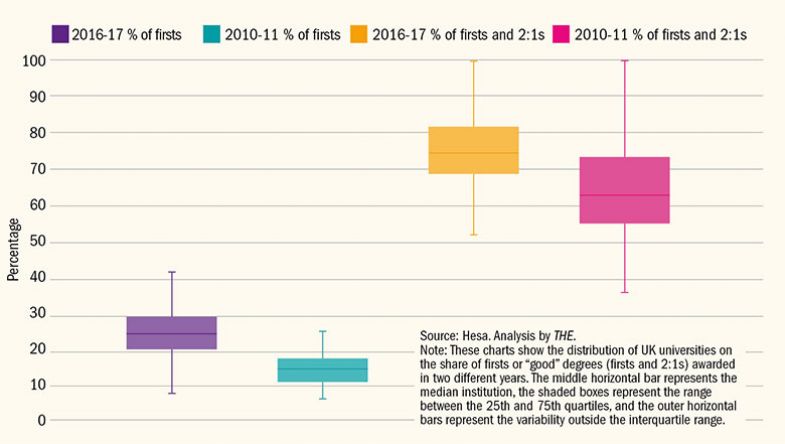

In 1996-97, just over half of undergraduates received a 2:1 or a first; 20 years on, three-quarters do. Firsts in particular are arguably no longer the special category they once were. The 8 per cent of students who earned one in 1996-97 ballooned to 26 per cent by 2016-17. Meanwhile, the share ending up with a 2:2 or a third-class degree has almost halved.

Some of the steepest rises in good degrees appear to have occurred in recent years: something not lost on critics of higher fees in English universities, who believe there must be some link with the trebling of the tuition fees cap to £9,000 in 2012 and a dilution of academic standards in the face of more assertive student-consumers. Even defenders of the current system, such as the former universities minister Jo Johnson, have been strident in their belief that “grade inflation” is “ripping” through the sector. Just last week, a report from right-leaning thinktank Reform was the latest to take aim at the issue, suggesting that some kind of national assessments may be needed to fix the problem.

Johnson’s brainchild, the teaching excellence framework, also attempts to take it into account in its assessment of institutions. A measure of grade inflation is included in the recent second round of results, although it is only one metric among many, and its inclusion in the forthcoming subject-level TEF was roundly criticised by respondents to the recent consultation.

But do these rises in high scores actually tell us anything about standards? Could there be other factors affecting student performance that can explain what is happening? And what is the experience in other countries?

For Ray Bachan, a senior lecturer in economics at Brighton Business School, the upwards trend in the proportion of firsts and 2:1s has sometimes been too easily badged by the media as grade inflation, which strictly speaking is a rise in the grades awarded for the same level of performance. Often, he says, articles on the topic are “mainly a commentary on things going up, not why they’re going up”. Nevertheless, he adds, that does not mean that grade inflation does not exist.

A 2015 study by Bachan, published in the journal Studies in Higher Education, looked at grading data from 2005-06 to 2011-12 and attempted to control for some of the other factors that could have influenced grades. The study, “Grade Inflation in UK Higher Education”, suggested that there was a case to answer in the way grades rose around 2010. He believes there were two main potential causes. One is changing methods of assessment towards a more “competencies-based” system. The other is increased pressure on institutions to do well in domestic league tables. This pressure may have increased further since the study was done: competition in student recruitment has been intensified by the removal of numbers caps, beginning in 2014-15.

Domestic rankings in the UK not only use metrics based on the proportion of “good” degrees achieved by each university’s students but also use data on student attitudes taken from the National Student Survey.

“I would suggest that students are happy…if they have high grades,” Bachan says. “The minute they come through the door, they want [at least] a 2:1” because “they know from deliberations in schools and the pressure of parents and everyone else in society [that] they can’t get a job unless they get a 2:1”.

Distribution of UK universities for share of firsts and ‘good’ degrees

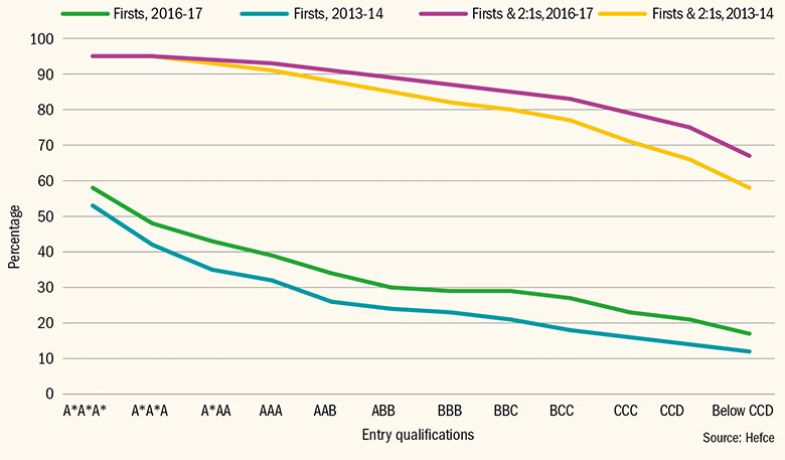

Percentage of 2013-14 and 2016-17 qualifiers gaining ‘good’ degrees

Bachan is about to undertake further research on grading since 2012, but his feeling is that after controlling for other factors there may well be grade inflation in the system. There is already some evidence – buried in one of the last reports released by the Higher Education Funding Council for England before it was replaced by the Office for Students – that the media may not be crying wolf on grade inflation since the fees rise. Data from that report, “Differences in Student Outcomes: The Effect of Student Characteristics”, show an increase in the share of firsts and 2:1s awarded at every level of prior attainment in terms of A-level school exam results.

This suggests that at least some of the rise in grades cannot be because students are arriving at university better prepared, although alternative explanations are also proffered. The Reform report points the finger at changes to the degree algorithms that convert students’ marks to final grades. Others suggest that students are more diligent than they were previously; this is the explanation preferred by students. Daisy Eyre, president of Cambridge University Students’ Union, says: “When the minister for higher education is saying ‘grade inflation is terrible’ and ‘students are getting better grades for doing less work’ it is really frustrating and kind of insulting from a student perspective.”Another explanation is that teaching standards at university have improved – perhaps as universities have placed a greater emphasis on teaching in the era of £9,000 fees and the TEF. But, as all the controversy around the TEF demonstrates, that is difficult to demonstrate.

Reacting to the Hefce data earlier this year, Bernard Rivers, a former visiting fellow at Cambridge, who has analysed the rise in grades awarded at the institution, said that although it was “theoretically conceivable” that students had worked harder or received better teaching in recent years, he was not convinced.

“What on earth could cause such a significant increase in talent or diligence?” he asked. “No. This is grade inflation, without a doubt.”

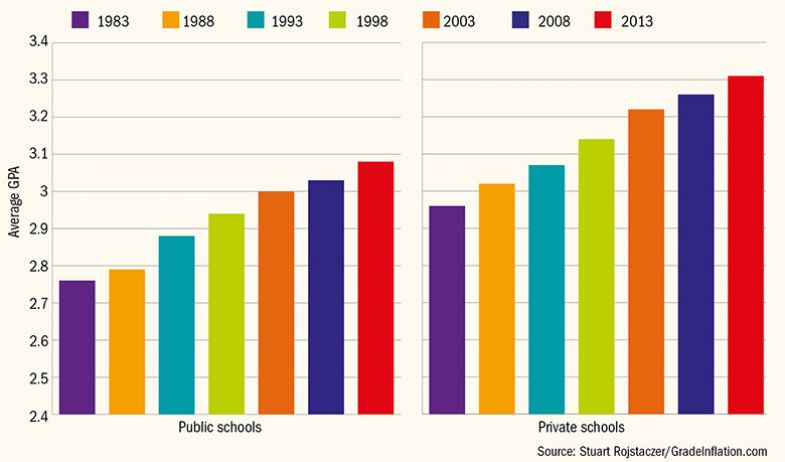

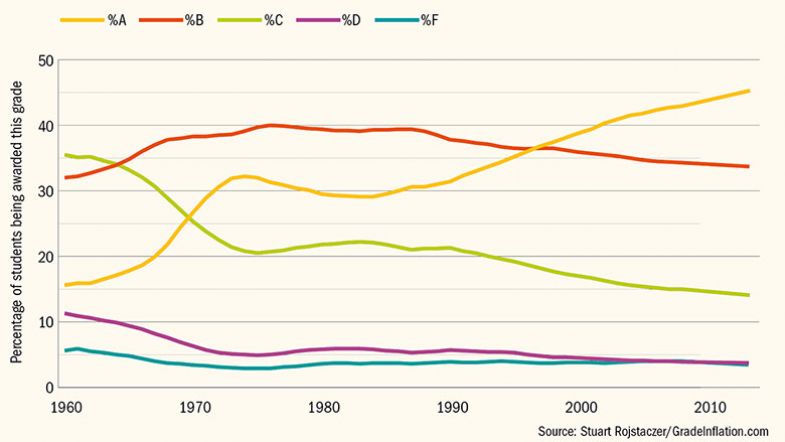

In North America, there are experts on grading standards who are in no doubt that the “student as consumer” trend has a lot to answer for. Regarding the US specifically, possibly the most comprehensive project to gather grading data, published on GradeInflation.com, has been undertaken every few years by Stuart Rojstaczer, a former professor of geology at Duke University, and Christopher Healy, a professor of computer science at Furman University. The data show a consistent rise in both the percentage of American students achieving A grades and the average GPA (the final grade point average of a students’ marks) since the late 1980s.

Like Bachan, Rojstaczer points to student satisfaction surveys as being the piece of the puzzle that links academic marking to grade inflation: “Student-based course evaluations become an essential means to evaluate instructor quality, and instructors quickly learn that high grades are critical to receiving high evaluations,” he says.

Bachan points out that the tenure system makes the US particularly prone to grade inflation since tenure decisions are based partly on student course evaluations. This means that untenured academics “have the incentive to push their grades up because that gives an impression of their teaching abilities”.

Rojstaczer also attributes grade inflation to students becoming more demanding in the wake of fee rises. He believes it is no coincidence that private US universities – with their hefty fees – have higher GPAs. “When you charge that kind of money, you tend to view your students as customers who need to be satisfied, rather than acolytes in search of knowledge,” he says.

Average GPA at four-year colleges and universities in US

Grade distribution in US four-year colleges over time

In Canada, meanwhile, some observers believe grading has been affected by funding being distributed between departments depending on the popularity of their courses.

James Côté and Anton Allahar, professors of sociology at the University of Western Ontario and authors of the 2007 book Ivory Tower Blues: A University System In Crisis, presented data in their university newspaper in 2010 that suggested the introduction of such “enrolment-contingent” – or, more pejoratively, “bums-on-seats” – funding at their institution in the late 1990s provoked a spike in grades. This is because departments where enrolments were falling felt under pressure to relax their grading practices to make their courses more attractive, leading to an “arms race” in grade inflation.

Côté says that although the analysis was at a micro level, the principle can be assumed to apply more widely because it is hard for individual universities to push against the tide of grade inflation alone without losing out in terms of student enrolments and grade outcomes.

“Anyone who tries to reverse [grade inflation] will be the object of great pressure from many sources, not least parents and students,” he says. This is as true when the cost of education is borne by general taxation as it is when students pay fees, so the onus is on policymakers to address the problem at the wider level by changing the incentives.

“In countries like Canada and the US, education is a provincial or state mandate, so [action against grade inflation] has to start there,” he says. “But…there is little incentive for individual schools or regions to go it alone. It is a race to the bottom, without signs of political will to do anything about it.”

One country that offers an opportunity to look at the effect on grades of both tuition fees and performance-linked public funding is Germany.

Thomas Bauer, professor of economics at Ruhr University Bochum, co-authored a 2011 paper, “Performance-related Funding of Universities – Does more Competition Lead to Grade Inflation?”, that looked at reforms brought in by several of the German Länder from the 1990s onwards, whereby indicators including graduation rates were linked to funding.

Although his own day-to-day experience suggests to him that these reforms were a driver of grade inflation, the study did not find enough evidence to demonstrate a link. However, Bauer says that rather than constituting evidence of the absence of such a link, the study probably just reflected the fact that it was too early for such an effect to be manifested. The simple fact was that the reforms meant that departments received less money if they failed to pass students, he points out.

Ideally he would also have liked to analyse the effect on grading of the brief introduction of tuition fees in some German states in the mid-2000s. However, there were not enough data to model this. But, again, his experience “with tuition fees was that grade inflation accelerated”. Time spent earlier in his career in the US convinced him that charging students influences grades, he adds, because departments immediately feel unable to fail too many students.

“When I started studying [in Germany] it was clear that the purpose [of grading] was to get rid of as many students as soon as possible. So you had failing rates of 50 to 60 per cent in the first introductory lectures,” he says. But when he started working in the US and tried to fail that many students, he was immediately reminded that the students were paying for their education.

“In Germany, during the short period of time we had tuition fees, you saw exactly the same – and students also changed their attitude,” Bauer says. “I had a colleague who was really shocked when a student told him: ‘Your lecture cost me €15 [and] it was not worth it.’”

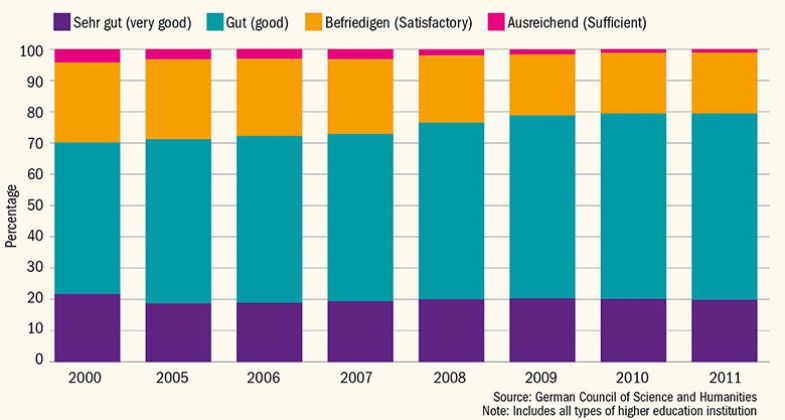

The most accessible raw data on grading in German universities – published by the German Council of Science and Humanities (Wissenschaftsrat) in 2012 – does indicate a significant drift upwards in the number of German students getting top marks between 2000 and 2011.

On all courses except doctorates, about 70 per cent of students in 2000 received the top two marks of “Sehr gut” (very good) and “Gut” (good); by 2011 it was close to 80 per cent, while those receiving the lowest pass grade (“Ausreichend” – sufficient) dropped from 4 per cent to 1 per cent.

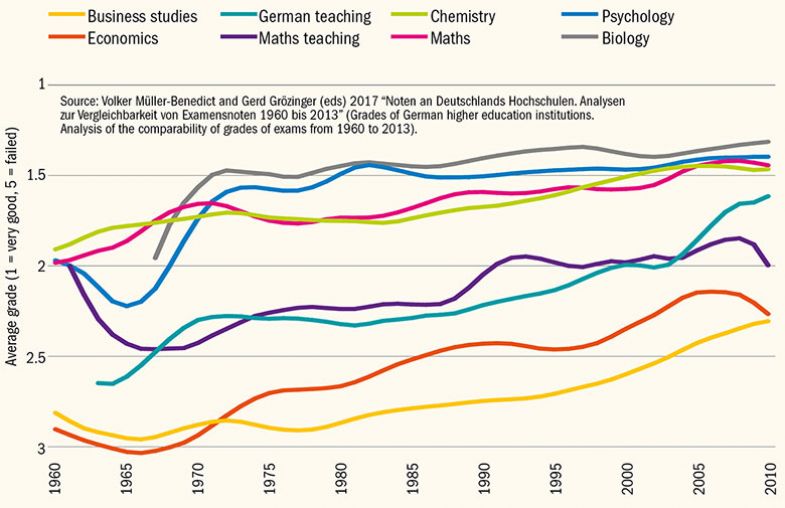

German grading over time in six disciplines

German grade distribution

According to Christian Tauch, head of the education department at the German Rectors’ Conference, the Wissenschaftsrat data brought rising grades to public attention in Germany, where, previously, it had not tended to be a “burning issue”.

But many people simply blamed the country’s “lowering standards” on their usual scapegoat: the Bologna Process, and its introduction of bachelor’s and master’s degrees. This was despite the report’s demonstration that marks in traditional higher education qualifications such as the magister had also gone up.

Meanwhile, extensive research by an academic at the University of Flensburg has shown that grades at German universities have been going up for several decades, casting doubt on claims that recent policy changes are to blame.

The analysis by Volker Müller-Benedict, a professor in the department of central methodology, some of which was presented at the UK’s annual Society for Research into Higher Education conference last year, suggests that grade rises happen in “cycles” and in some subjects these appear to be linked to fluctuations in the job market.

However, marks do not fall to the same extent as they rise and Müller-Benedict attributes this one-way direction of travel in grades over the long term to factors that are not dissimilar to those that feature in the UK and US debates.

“Better grades are a win-win situation for all participants,” he says. Students are clearly more content with better grades, but academics also appreciate the lack of complaints and the conveyed impression that they taught the students well.

Müller-Benedict says the solution to grade inflation is to disentangle teaching performance from grading behaviour: “[Academics] should never be evaluated by the grades they give,” he says.

So although Germany has retreated from a more marketised model, the underlying cause of grade inflation appears to be similar: the monitoring of teaching.

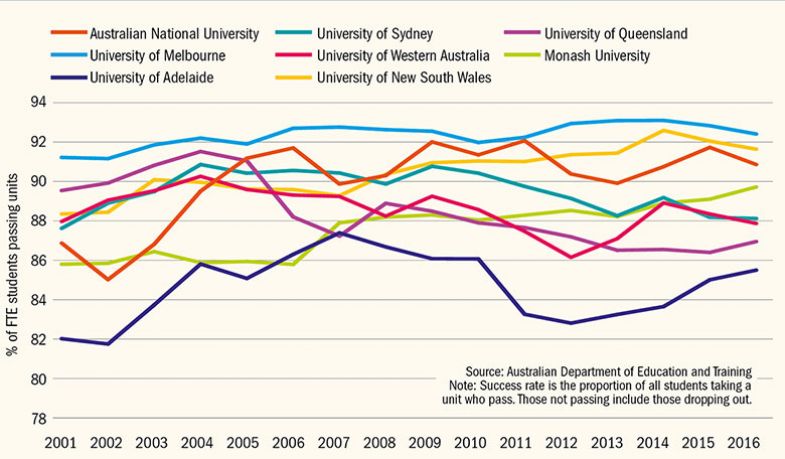

Another interesting case study is Australia. Like England, students there pay a significant chunk of their degree costs through income-contingent loans. But while this may be set to change with the government’s planned introduction of league tables likely to draw on the country’s existing Student Engagement Survey, academics there are not currently judged to any serious extent on the basis of student feedback. And there is scant evidence of rising grades.

However, the extent to which this merely reflects a lack of published data on grading is unclear. There are no sector-wide datasets on university grades, partly because there is no uniform grading system. For instance, the University of Melbourne uses a similar honours classification system to the UK, but other universities use grades such as “distinction” and “high distinction” – but often with different score boundaries.

The only data published by the federal government that show a measure of student performance relate to the proportion of students who pass their courses.

These data show no real changes over time in pass rates at different institutions. However, without complete data transparency it is difficult to conclude definitively that the country is immune to grade inflation. Some Australian universities approached by Times Higher Education for data refused to release figures on the grounds that varying grading systems made comparisons meaningless.

It is also notable that one of the only detailed empirical pieces of research on Australian grading in recent years, published by Gigi Foster, associate professor in economics at the University of New South Wales, in 2012, did generate concern. The paper, “The Impact of International Students on Measured Learning and Standards in Australian Higher Education”, published in Economics of Education Review, presented evidence that suggested that overseas students were being marked more softly than their domestic counterparts on final course grades, and caused quite a media stir.

But it is also possible that the general lack of data on Australian grading behaviour actually guards against grade inflation because it prevents students, academics and university administrators from having the information that fuels it. According to Foster, more data could impel the leaders of universities thereby demonstrated “to lag their peers in awarding good marks…to pressure their academics to adjust their marking standards downward”.

Group of Eight ‘success rates’

Andrew Norton, higher education programme director at the Grattan Institute thinktank, adds that the lack of available data “does mean that students don’t have a perception that they are disadvantaged by attending a hard-marking university (or faculty or department), so this has not generated pressure for more generous grading”.

However, Norton says that the scant research on Australian grading “hampers analysis” of the issue. And Foster has called on the government – so far without a “meaningful” response – to release more data. “Making defensible scientific judgements about anything is made easier when we have good data,” she says.

According to Norton, another possible explanation for the lack of grade inflation in Australia could be the common practice of marking students relative to their peers, as opposed to examining whether they have met some supposed absolute standard. He has on “multiple occasions heard academics say that even though there may not be a strict policy of marking to a curve, they have to justify substantial differences from some expected pattern”.

Academics in other countries have proposed a similar practice as a solution to grade inflation. For instance, Bauer says that giving the best student the top mark and then marking others relative to that score is a way of achieving a “very stable grade distribution”.

But wouldn’t this make comparing the graduates of different universities and disciplines – as employers in particular would like to do – even more fraught that they already are?

“I actually think that what is most important is information that a particular student was, say, the third best in his cohort,” Bauer responds. “It would be much more informative if you had this [information] together with how big the cohort was.”

Müller-Benedict, too, thinks the key is more information about the context of a student’s grades. After each grade on a student’s transcript, “there should appear a little diagram of the distribution of all grades” from previous years in that course. “Then we would have complete transparency for where this student is compared with the university’s mean grade, the discipline’s mean grade and for this cohort of students.”

Such a scenario may be wishful thinking, but if students really do have as much power as is claimed, it may make sense for them to push for it given that they arguably suffer the most from unexplained rising grades.

As the Cambridge University Students’ Union’s Eyre puts it: “There is no proof and it is pretty horrible that the first conclusion that people in higher education jump to is grade inflation, rather than that students are working harder.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Grades anatomy

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login