UK home secretary Amber Rudd’s speech to the Conservative Party conference last week confirmed what the higher education sector has long suspected: the Home Office does not understand UK universities. It seems Rudd and her officials do not even know how many universities there are in the country, for she conjured up a picture of “hundreds of different universities”. In fact, there are only about 150.

The speech promised yet another crackdown on international students, but this time there are to be starkly different rules for different institutions. There could even be different rules for different courses within single institutions: “Our student immigration rules should be tailored to the quality of the course and the quality of the educational institution,” Rudd said. Ironically, at the same time as she was speaking, and just a few metres away from her, I was presiding over a discussion on students’ mental health that included people from a rich mix of diverse institutions, who are keen to work together on this sector-wide challenge.

We can’t say we weren’t warned. For years, the Home Office has been blowing a dog whistle. On the one hand, it has reassured people that it is relaxed about “the brightest and best” coming from abroad to study in the UK. That sounds nice but it has always been cover for wanting to stop anyone else from coming.

Pretty much everyone in the higher education sector has pointed out the educational, financial and soft power benefits of educating people from other countries. At the Higher Education Policy Institute, we have published two surveys showing that students believe they benefit from studying alongside people from other countries. We have also undertaken desk research showing that a quarter of the world’s countries are led by someone educated in the UK’s tertiary sector. Such evidence is accepted by many parliamentarians, but it has fallen on stony soil in the corridors of power.

It is sometimes alleged that Whitehall understands only two universities, Oxford and Cambridge, and one course, PPE (philosophy, politics and economics). That is unfair. After all, Rudd read history at the University of Edinburgh. But it is not a million miles from the truth. When I worked in the old Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, we saw it as a core part of our job to remind our colleagues of the diversity of the higher education sector and of its strength in breadth. It was a constant and uphill fight, but we won some of the skirmishes.

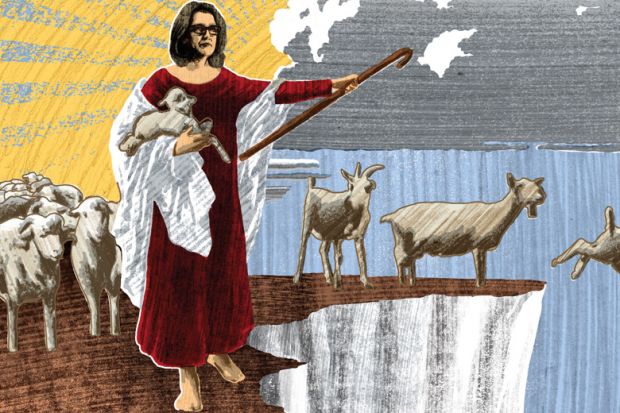

The latest announcement suggesting the sector is to be split into sheep and goats, according to “quality”, suggests the war itself is being lost. But ministers may find they have overstretched themselves. It is possible the Home Office’s latest attack is the equivalent of invading Russia – a step too far for pretty much everyone who has ever tried it. That is more than wishful thinking because the new crackdown is based on a fallacy. It is wrong to think there is an easy way to determine which courses and which institutions are good enough, and which are too poor for international students.

One way to try to do it would be to focus on those universities that appear to be world class in the league tables. But, as everyone knows, such tables are typically better measures of good research than good teaching (with one or two honourable exceptions). Yet international students presumably come to the UK hoping to be taught well.

Another option would be to say that only universities in a particular mission group or two – most obviously the Russell Group – pass the test. But mission groups are self-selecting, many universities are not in one and the groups themselves would lose their value were institutions to join in order to secure the right to recruit international students.

A third option would be to piggyback on the teaching excellence framework. Perhaps because it was being designed while the summer Olympics were on, this is to have gold, silver and bronze awards. There is some logic to using the TEF in this way. For example, it is clearly more sensible for the Home Office to use a pre-existing official measure that has been agreed with the sector than to devise its own from scratch. But the TEF rankings are very unlikely to match ministers’ prejudices about which institutions should be allowed to recruit international students. So they won’t match the policy intention.

All the options have one other fundamental problem. The government’s stated primary motivation for toughening up migration is to help British people succeed in life. That is why, for example, companies are going to be pressed into training and employing Britons before those from other countries. It would be distinctly odd for a government that takes such a pro-British stance to say that some university courses are good enough for home students but not good enough for those from other countries.

Before his all-too-early death in 2015, Sir David Watson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, asked whether the UK still had a national higher education sector. As he noted, it is clearly stretching at the seams, with greater devolution, more alternative providers and so on. But Sir David’s answer to his own question remains as topical as when he wrote it: “There is still a sort of mutually-assured higher education enterprise, which government and others would like to be more differentiated…But many of the key players in this enterprise refuse to behave.” Long may it remain so.

Nick Hillman is director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and was adviser to former universities and science minister David Willetts.

后记

Print headline: Sheep v goats: baad idea