There is a common view in universities that the tenure of UK vice-chancellors is getting shorter. The growing demands of the job, the increasing marketisation of higher education and more active governing bodies are thought to have increased turnover. One-off rows at the top of institutions, such as at Plymouth University and Kingston University, appear to provide backup for the idea.

But there is little evidence beyond the occasional anecdotes. So we set out to test the idea that serving vice-chancellors have a shorter lifespan than in the past. Because so many UK universities are comparatively new, we had to concentrate on the subset of UK institutions that have had university title for many decades. That meant tracking the leadership of our oldest universities over the past half century.

We then crunched the data in three different ways.

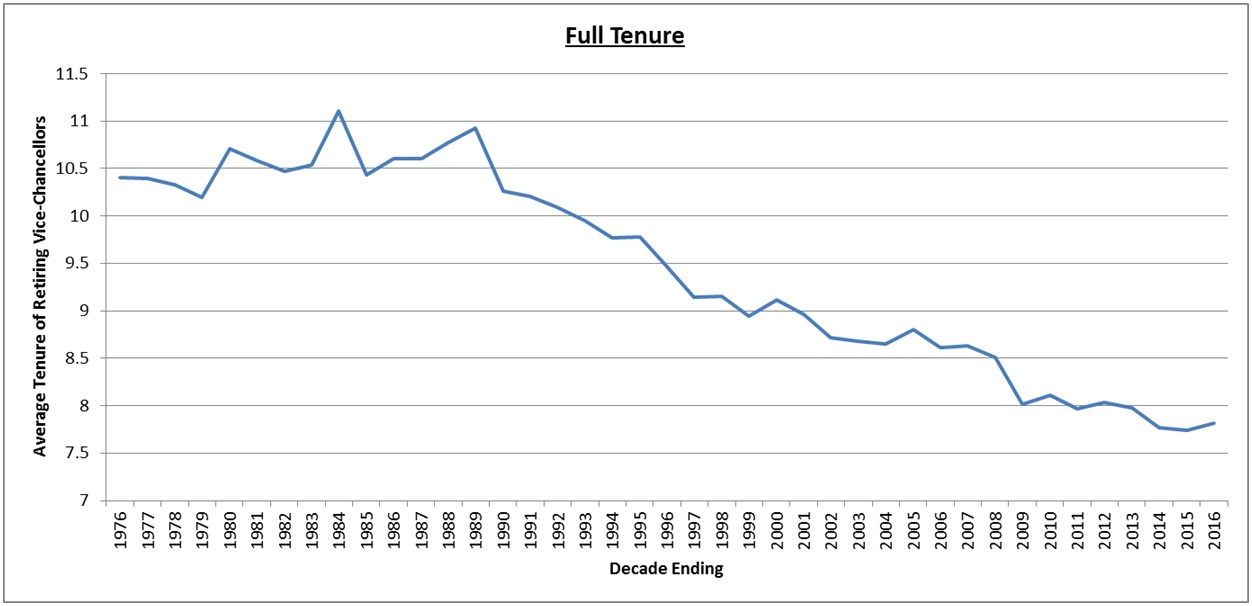

First, we looked at the tenure of each vice-chancellor when they ended their term in office. This suggests that the length of time people stay in the job has indeed become shorter. But the reduction is less than might be expected. The average tenure of a vice-chancellor was once a little over 10 years, whereas it is now a little below eight years – a reduction of about 20 per cent.

Close inspection shows that this was not a consistent decline. There was a relatively stable period in the 1970s and 1980s, with vice-chancellors serving an average of 10 and a half years in office. Then, from the early 1990s, there was a gradual but continuous decline of roughly one month each year. As a result, the universities in our study collectively now make about six new appointments each year on average, compared with about five in the past.

Initially, we excluded four older universities – Oxford, Cambridge, London and Wales – from the analysis. This is because their past practice of appointing vice-chancellors with short term limits of two to four years could have distorted the results. But, as a second way of crunching the data, we added them in to see how much difference it made.

As expected, with these four institutions in the study, there is a similar but less dramatic decline – from about nine years to seven and a half years.

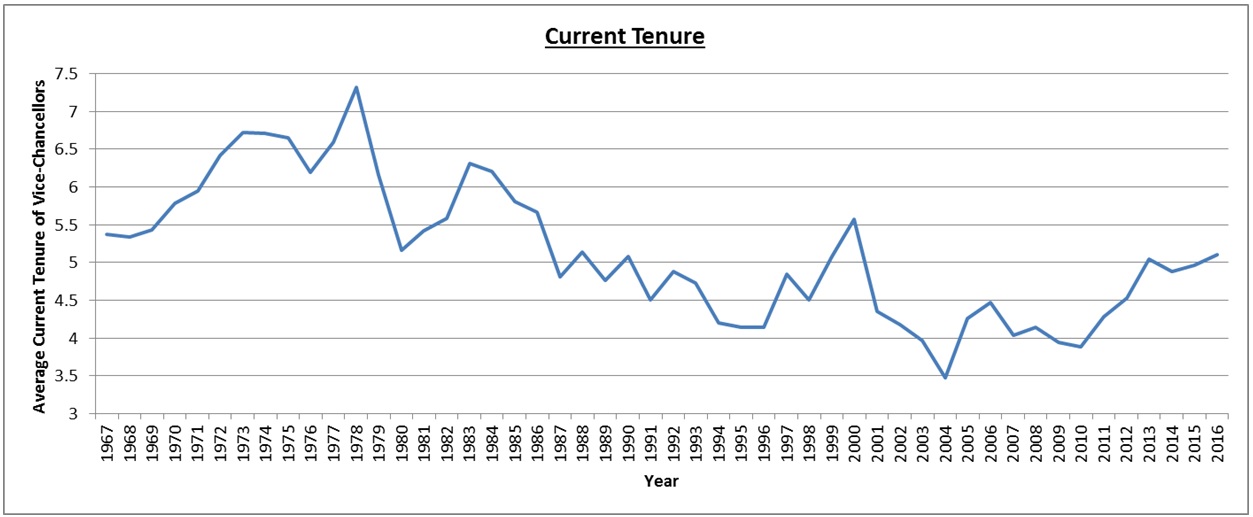

Our third way of testing the idea of ever-shorter tenures was to take annual snapshots of every incumbent vice-chancellor’s tenure, as opposed to their full tenure. This method also reveals a downward trend, from about six years in the 1970s to about four years in the late 2000s. Intriguingly, there has been a pick up back to five years in the current decade. Six current vice-chancellors have served more than 10 years.

The small sample size and the inherent volatility make it tricky to arrive at definitive conclusions when looking at the data this way. For example, when lots of departures coincide, the average tenure reduces: in 2004, it fell to three and a half years. Long-serving vice-chancellors departed in ways that were individually unremarkable but collectively exceptional.

Our analysis is a long way from being exhaustive. For example, no allowance is made for the fact that some vice-chancellors go from leading one institution to leading another. Among the country’s most well-known current vice-chancellors, Michael Arthur of University College London, David Eastwood of the University of Birmingham and Louise Richardson at the University of Oxford have all previously been in charge of other institutions.

The research excludes the UK’s longest-serving university leaders, such as John Cater of Edge Hill University (appointed in 1993) and Tim Wheeler of the University of Chester (appointed in 1998), because their institutions were not universities at the start of our time series – nor even when their current leaders were first in post.

Overall, the tenure of serving vice-chancellors is almost identical to the tenure of current heads of FTSE 100 companies, where the average is also a little over five years. But it compares very well against the tenure of professional football managers, who currently average about 15 months in the job.

It also compares well to politicians. The last time the most senior education minister lasted more than six full years in the job was Sir John Eldon Gorst, who was appointed in 1895 and left office in 1902.

In the top political jobs, there are often term limits of about eight years that protect against people becoming stale and out of touch. Some might think that this is a sensible idea that should be applied to university leaders, too. After all, if Margaret Thatcher or Tony Blair had been forced to retire after eight years, then they could have done more to protect their historical record.

On the other hand, the case against term limits is also strong. Without them, this year’s US presidential election could have been Barack Obama versus Donald Trump rather than Hillary Clinton versus Trump, which some people might conceivably have welcomed.

Nick Hillman is the director of the Higher Education Policy Institute and Tom Huxley is a freelance researcher.