Mathematics has an uncanny ability to solve problems that do not yet exist. The Nobel Prize-winning physicist Eugene Wigner called this the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics”. He described, for example, how “very scanty observations” about an apple falling from a tree led to our understanding of an entire dynamic planetary framework.

Maths currently brings more than £200 billion per year to the UK economy, or 10 per cent of GDP. Innovations in artificial intelligence, quantum computing, driverless cars and superfast broadband would not be possible without it. Its contribution to computer modelling of the Covid-19 outbreak and the roll-out of vaccinations has been invaluable. And it is also central to national security, through the work of GCHQ, the communications monitoring centre.

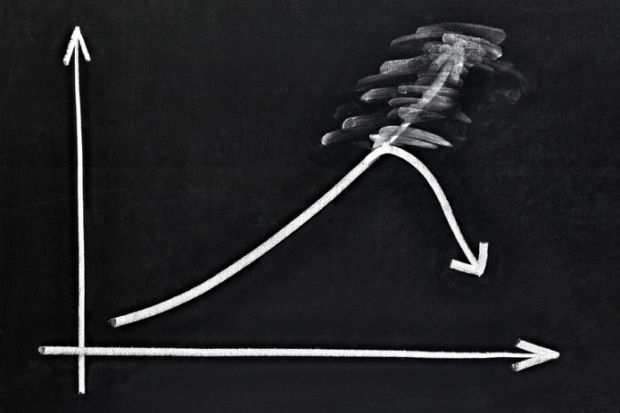

But when it comes to prioritising spending, the impossibility of foreseeing how work on highly theoretical conundrums today may end up helping solve the puzzles of tomorrow is a problem. Politicians, university leaders and research funders can easily be tempted to put money into subjects that provide quicker economic returns.

Politicians, in particular, have a reputation for short-term thinking. However, this government deserves some credit for forward planning. A couple of months before the first Covid lockdown in the UK, and a couple of weeks before Rishi Sunak’s appointment as Chancellor of the Exchequer, it promised a £300 million uplift in funding to support “experimental and imaginative mathematical sciences” research, including more PhDs. In addition, Sunak recently announced extra funding for AI posts.

As Sunak finalises the spending review he is to unveil on Wednesday, and contemplates the enormous hole in the public finances dug by the pandemic, no doubt he has a lot of calculations to make about current crises, such as easing social and geographical disparities and improving funding for the NHS and social care. But his resolve to fund the mathematical sciences must not falter. If he confirms the promised £300 million, it will be totemic, a welcome relief not just for maths but for all subjects that require time and money to deliver their benefits to society, knowledge and the economy.

Academics are often unfairly accused of living in ivory towers, but many of us were brought down to earth by the hard economic facts of university business models a long time ago. While the current golden age of mathematics should be celebrated for its great innovations, instead departments around the world are facing closure.

The University of Leicester, for instance, closed its pure mathematics research group (among other subjects) earlier this year, prompting the launch of the Protect Pure Maths campaign, for which I am a spokesman. There is also a steady stream of reports of cuts at other non-vocational departments at other universities, including languages at Aston University and archaeology at the University of Sheffield. These pressures on universities are a growing trend globally, too. Macquarie University in Sydney, for example, has slated maths and science courses for closure.

The maths cuts come despite the subject’s enormous popularity in secondary schools, constituting the most popular A level, and its steady enrolment numbers at undergraduate level. The problem lies in the disparate departmental fortunes that the overall figures disguise; while student numbers in certain mathematics departments have grown considerably over the past decade – some have doubled or even trebled – other departments have seen dramatic reductions. And while some vice-chancellors may see this decline as just a short-term fluctuation in the student market, others may see in it a trend and, in the constrained Covid environment, make hasty and brutal cuts. That is especially true if they have overextended themselves with ambitious building programmes based on assumed large numbers of overseas students.

In these circumstances we believe that the government should step in to protect the longer-term interests of the country, supporting parts of the intellectual economy that struggle in the short term but provide profound, as yet unknowable returns in the future.

But we also appeal to vice-chancellors not to vandalise departments that have done exceptionally well for decades based on near-term considerations. Remember that the world’s leading universities all have mathematics departments, and that maths infrastructure cannot easily be reconstituted years down the line. Do university leaders really want to set their universities apart from the elite in this way?

Despite Sunak’s good intentions, the unprecedented scale of the bill for “building back better” post-Covid could jeopardise the £300 million funding for maths. But if ministers are serious about levelling up, they should remember that mathematics is one of the most inclusive subjects, attracting and liberating thousands of students from poverty or repression around the world in recent decades. I have supervised two brilliant PhD students who came from underprivileged backgrounds and whose lives have been transformed by their mathematical abilities. It would not serve social diversity if it was impossible to study a core subject like mathematics at higher levels in some geographical areas.

The government could also go further in its recognition of mathematics’ economic value by making it easier for UK businesses to claim research and development tax credits explicitly for mathematical research.

As academic guardians of the country’s nascent intellectual property, we must make the case for maintaining the longer view, so that the UK remains both a prosperous nation and a maths superpower.

Jon Keating is spokesperson for the Protect Pure Maths Campaign, president of the London Mathematical Society and Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Oxford.