Jan Rowe was in her office when an email arrived that would determine the fate of her whole department.

Liverpool John Moores University, where Rowe was head of initial teacher education (ITE), has taught teachers for decades, dating back to its merger in 1983 with the Mott College for Education, which itself was founded to address national shortages in the profession after the end of the Second World War.

Yet that could all have been swept away in an instant thanks to the Department for Education’s (DfE) “market review” exercise, which forced all providers in England to reapply for accreditation, the results of which were in Rowe’s inbox.

This was 2022, and, mindful of staff morale coming out of the pandemic, Rowe and a few others had shouldered the burden of the process. Nevertheless, its results would have widespread repercussions for the School of Education and the university more widely.

“I remember distinctly when the email came through from the DfE,” Rowe says. Opening it was “a horrible experience for me because I thought, ‘I have to click on this now and then either go to people and say, “Don’t worry, we’ve got it” or I have to tell them we haven’t.’”

Luckily for her, it was the former. However, after two rounds of applications, 13 universities, many of them with equally long histories in the field, were stripped of their ability to offer courses that lead to qualified teacher status (QTS), essential for those hoping to work in most UK schools.

For Rowe, the process was all too much, and she stepped down from her role as head of ITE last year. It was the culmination of a trend for ever greater government involvement in all aspects of teacher education that, from September, will see new regulatory requirements imposed on providers that assess compliance with the DfE’s “core content framework” (CCF), which many see as a de facto national curriculum.

“Imagine if I had been the head of history and the DfE had said, ‘We need to see what you are teaching and validate that you are teaching history in the way we think it should be taught,’” Rowe says. “I think across the country there would have been uproar. We are universities: places of freedom of thought, where diverse views are valued. Yet the DfE is approving what our academic staff can and cannot teach, down to the level of some of the PowerPoint presentations we are using in lectures.”

The changes have been fuelled by a long-running narrative, inflamed more recently by the culture wars, that universities are producing teachers unprepared for the classroom because courses are too focused on theory and “woke ideology” when they should be teaching the science of learning.

The move towards close government oversight has made the English ITE sector one of the most tightly regulated in the world, according to many observers. Yet echoes of what has happened in England are also playing out elsewhere as politicians seek greater control over education academics, whom Michael Gove, the influential former English education secretary, derided as part of “the Blob” of educationalists he blamed for eroding standards in schools. And new routes into teaching are becoming more commonplace globally, such as apprenticeships and private training providers, which diminish or do away entirely with universities’ role.

Yet Rowe believes that the English government’s power grab has gone largely unnoticed in other university departments even though it has set a precedent that could be replicated in other fields.

“The tragedy of it is that England had a really good system,” says Viv Ellis, dean of the Faculty of Education at Monash University in Australia, who has also worked in England and is co-author of a recently published book The New Political Economy of Teacher Education: The Enterprise Narrative and the Shadow State. “It wasn’t perfect, but nothing is, and, internationally, countries have always sought to develop a system for preparing teachers that integrated practice and theory. Through successive reforms from the ’80s and ’90s onwards, England achieved that, and universities managed to make it work, while many other countries have still not got there. Ofsted [the schools regulator] thought what they were doing was good; students thought what they were doing was good; schools thought what they were doing was good. It is a real tragedy that that has just been trashed.”

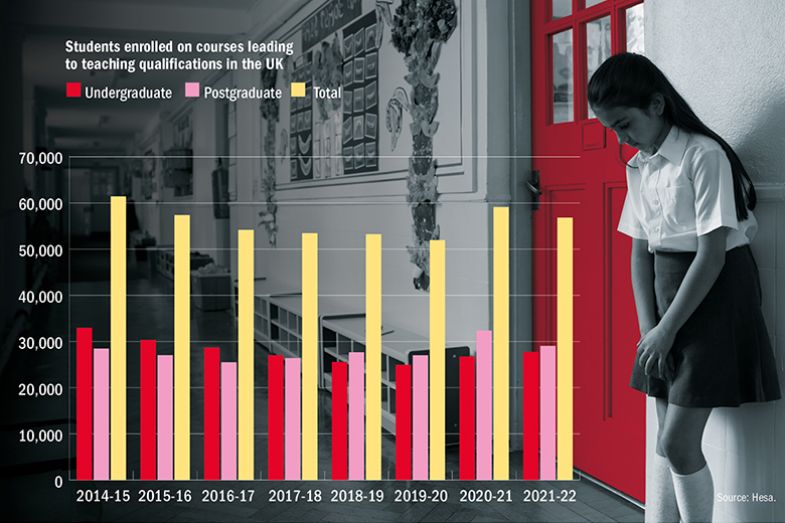

Regardless of their quality, the popularity of teaching courses has been on a steady decline in England – as in most other parts of the world – for years.

A government target to recruit 35,540 students on to postgraduate certificate in education (PGCE) courses in 2023-24 was missed by 38 per cent, with only half the required number of secondary school trainees recruited. Nor was that an isolated year: recruitment targets have been met in only one of the past seven years.

Australia has seen similar falls, with Jason Clare, the education minister, highlighting in a speech last September that there has been a 12 per cent drop in student teacher numbers in a decade. He frequently states that 50 per cent of students who start a teaching degree do not finish it, although this statistic is based on students not completing within six years – many may just be taking longer.

In the US, meanwhile, the number of students completing higher education programmes in teaching fell by a third between 2008 and 2019, according to a 2022 report by the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education (AACTE).

The reasons behind these slumps are manifold, not least the general impression of the profession as demanding a lot of hard work for a relatively low salary.

“The job of a teacher is nearly impossible at this point, if you think of all of the needs a child has,” says Lynn M. Gangone, the president and chief executive of the AACTE, who sees the solution not as more regulation but, rather, as greater involvement by universities in the continued development and training of teachers post-graduation.

The declines in student numbers are reflected in growing teacher vacancies worldwide, driving up the ratios of teachers to pupils in schools. And for universities whose finances are dependent on teaching students, falling recruitment has the potential to be just as damaging as it is for schools.

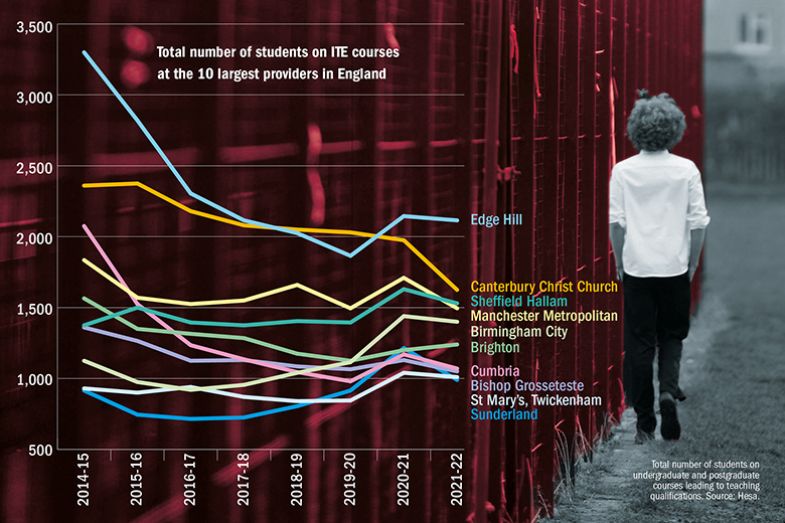

In England, the University of Huddersfield – which has undergone several rounds of redundancies in recent years – had 1,235 students enrolled on teaching programmes in 2014-15. This had dropped to 520 by 2021-22, according to the latest figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency. And Edge Hill University, the institution with the highest number of teaching students in the country, had more than 2,000 in 2021-22 out of a total student population of just under 12,000. But that is a decline of one-third on 2014-15, when it had more than 3,000 on its teaching programmes.

The overall decline in the number of students on courses leading to teaching qualifications was only 7.5 per cent during that period. But post-92 universities in particular are “heavily reliant” on teacher education, says Ellis. “If they lose the numbers from educating teachers – especially in the current environment – they could be facing financial crisis.” Nor is it just the newer universities that need teaching students to survive. The UCL Institute of Education has close to 1,000 students enrolled on its teaching programmes, for instance.

Ellis believes that such financial dependencies have inhibited universities from pushing back against government interference: “If you say you are going to pull out [of ITE], it is writing a suicide note. It is extremely difficult for many, perhaps most universities, in the current environment, to exit the market.”

Many universities also see training local teachers as integral to their mission. “We are an anchor institution in a huge city that draws in hundreds of students every year,” says Lisa Murtagh, the head of the Manchester Institute of Education at the University of Manchester. “Eighty per cent of our trainees get employed within our region and become the mentors of the next set of trainees…This contributes significantly to the social responsibility agenda; if universities are not doing this work, it is very hard to see who else could do it.”

Most English universities offering ITE programmes have, therefore, had no choice but to adapt to whatever comes their way. And most have proved remarkably resilient, continuing to oversee about 80 per cent of teacher education.

James Noble-Rogers, executive director of the Universities’ Council for the Education of Teachers (UCET), says there has been a “cyclical” threat to universities’ involvement in teacher education throughout his career in the sector, which began in 1987. This is often fuelled by “ideological prejudice” and a misperception that ITE programmes are “airy-fairy” and sociologically based, “with no relevance to schools. [Politicians] never seem to grasp the fact most of university provision is school-based.” Still, he believes the market review represents the biggest threat England’s university education sector has faced in decades, even if it did not, in the end, result in the realisation of UCET’s worst-case scenario of almost all university-based providers being removed.

Sam Twiselton, who advised the DfE on many of the changes while director of the Sheffield Institute of Education at Sheffield Hallam University, has been critical of the market review – but not because she sees a conspiracy against universities. “There’s a much bigger threat to school-centred teacher training in these reforms than there is to universities. [Schools] just haven’t made a big, loud fuss about it,” she says.

She admits that when she first entered Whitehall, the agenda had been much more focused on getting universities out of ITE, but “the tone has changed a lot”.

Nevertheless, those institutions that were judged, in the DfE’s desk-based exercise, to be uncompliant with the core content framework have been left with a deep sense of injustice, largely because the decisions made appeared to contradict positive reports about provision from Ofsted and students.

“It was disbelief, really – a total sense of shock,” says Derek Moore, pro vice-chancellor (education, health and human sciences) at the University of Greenwich, recalling the moment the university learned it had lost accreditation. “At the beginning of the process, I don’t think any of us considered that the risks were as great as they turned out to be, and I think that was consistent across the sector. We felt we fully addressed the feedback we were given after round one and we were genuinely shocked that a university with a 120-year history of delivering teacher training – that has never failed an QTS Ofsted inspection, that is leading the way in things like mentoring and partnerships – would be considered to have not met the criteria.”

However, Greenwich, like many of the 13 universities deemed uncompliant, has been able to continue offering teacher education into the next academic year by forming a partnership with an accredited provider, the University of Derby. Similarly, students taking PGCEs at Durham University will have their QTS awarded by accredited provider Newcastle University; while the University of Cumbria has teamed up with the University of Warwick; the University of Sussex with the University of Chichester; the University of the West of England with Sheffield Hallam; and the University of East Anglia with the University of Worcester.

Greenwich’s partnership with Derby is “very positive, and I think we have got a lot out of working together, but it is not sustainable financially”, says Moore. “We are having to pay them to do quality assurance, which we don’t really need. So it is basically a 10 per cent tax imposed on us that other providers don’t have. If we don’t have an opportunity to go for reaccreditation, it is not clear how long this is sustainable for.”

UCET’s Noble-Rogers agrees that while partnerships have helped universities that failed in the market review to stave off the immediate threat of closure, they are not a long-term solution. UCET has called for accreditation to be returned to the universities automatically; failing that, the next window for accreditation should be opened as soon as possible, the organisation believes.

“The non-accredited partners have less freedom and autonomy to deliver programmes they think meet the needs of their local communities,” Noble-Rogers says. “There is some room to contextualise them but [it is] very limited in scope. And the risk for the accredited providers – and they’ve done a sterling job – is that they will be held to account by Ofsted for provision that is delivered in some cases many miles away, potentially by an organisation larger than they are.”

Some of the universities denied accreditation did not enter a partnership, and Hull, Plymouth and London South Bank universities have all closed PGCE programmes (although they continue to offer education degrees in various forms without the QTS element). And while Noble-Rogers would like all unaccredited universities to seek reaccreditation because “it is essential that universities are involved in the [training of the] next generation of teachers”, he believes it is still not impossible that an education department with “relatively small programmes” might close entirely.

“These are expensive programmes to run anyway and come with a huge regulatory burden,” he points out. "Some v-cs might say: ‘We don’t need to be in this game. Let’s use our resources to deliver more predictable and stable programmes.’”

Even accredited universities have hinted that they might pull out of ITE in opposition to the changes, with both the universities of Oxford and Cambridge having previously threatened to end their provision.

“Cambridge’s position on this has always been clear all the way through,” says Clare Brooks, professor of education at the university. “We are fully committed to quality teacher education. But if it got to a position where Cambridge felt that they could no longer do quality teacher education, then there would be some discussions around that, for sure.”

Universities’ withdrawal would further open up the ITE market to the raft of new providers – many of them schools and academy trusts – that were approved in the market review process. However, such providers are adamant that their ambition is to operate alongside – and not to usurp – universities.

“We are absolutely not here with the intention of replacing existing providers or positioning ourselves as better or worse or anything like that,” says Yalinie Vigneswaran, executive director of programme delivery for the Ambition Institute, an educational charity that was also influential in developing the CCF and is headed by Hilary Spencer, whose 15 years as a senior civil servant in the DfE included a spell as Gove's principal private secretary.

“What we are looking to do is to ensure there is more choice for people who want to get into teaching to work out what works best for them. We want to provide a route into teacher training that takes brilliant educational research and evidence and integrates that with meaningful opportunities in a school context.”

But while part of the stated DfE reason for the market review was to simplify and ensure consistency of provision, Liverpool John Moores’ Rowe says the proliferation of providers means that the system is now “even more baffling for anybody wanting to come in to teaching”. Moreover, she is wary of the effect the new providers might have on universities: “It wouldn’t surprise me if their numbers stack up pretty well, and it is a challenging time for recruitment; so, their gain may well be universities’ loss.”

The risk, she says, is that new providers’ courses will focus too heavily on the way the schools they work with operate, so their trainees will learn only one way of doing things. Universities, by contrast, have always sought to introduce their students to a range of approaches and diverse experiences, Rowe says.

On the other hand, such breadth has arguably become harder for everyone to deliver because of the CCF, which many education departments say places too many onerous restrictions on the way programmes are designed. Some educators also object to the content of the CCF, which emphasises cognitive science techniques that aim to ensure that trainee teachers can embed ideas in children’s long-term memories.

“We are making spaces in the curriculum to accommodate the changes,” says Manchester’s Murtagh. However, “some of our staff have found that very challenging, both morally and ethically. To have to demonstrate compliance to what we would describe as an authorised curriculum, authorised pedagogies, is very problematic.

“The challenge has been to people’s hearts and souls. It is about how much we commit to providing our trainees with information or reading materials that don’t sit that comfortably with us. We are trying to walk the line a little bit and provide opportunities to engage with [the merits of what is in the CCF] rather than take it as a given.”

Much of the documentation and justification for the CCF has focused on the fact that it is underpinned by the latest evidence of what works in teaching. But a 2023 study by Cambridge’s Brooks (with Jim Hordern, a senior lecturer in education at the University of Bath) found that the CCF espouses what she describes as an “extremely partial and narrow definition of what that evidence” was. “It was not selected from the full range of journals and came particularly from certain types of research, not massively stemming from English universities,” she says.

The feeling that academics who work in teacher education have been sidelined in the reforms is a constant bugbear for the sector.

“If you look at the people attending these key groups, where are the teacher educators?” asks Brooks. “They are really not very present in the discussion and debate. You have to ask who is defining teaching and what the role of universities is in the professionalisation of teachers.”

Sheffield Hallam’s Twiselton, who is now an emeritus professor, having stepped down from leading her department last year, was often in the room when such definitions were being discussed, sitting on the advisory group for the market review and chairing the CCF advisory group. She says part of the issue is the lack of large-scale research in the sector.

Her own PhD was “very qualitative in nature – small scale, case-study-based”. Yet while it was “highly illuminating and useful” and there is “definitely a role for that kind of research”, she “couldn’t honestly say it is robust enough for government policy to be based on it. The DfE has a team that scours the evidence base, and there’s not much out there that has the scale and robustness sufficient to base policy on. There is an issue with the right kind of evidence for what works in initial teacher education.”

The process behind the market review and the CCF was “far more evidence-based than anything else I’ve been involved in over the years”, Twiselton continues. But she denies that the result is a block on academic creativity, describing the CCF as just the “bare bones” of a programme.

“You have to do a lot of work with it to turn it into the type of curriculum you want it to be for your students,” she says. “Most people I speak to, including in universities, don’t see it as a straitjacket. I think after they got over the shock of feeling like it had been imposed on them, they began to see it as useful.”

A spokesperson for the DfE says: “Initial teacher education reforms are a crucial part of our wider overhaul of teacher development, creating high-quality training and professional development through each phase of a teacher’s career. The accreditation process was done with the support of Ofsted and is about fairly assessing the capability to deliver ITE from September 2024, in line with the new requirements developed following the market review.”

In Australia, a report published last July by a government-convened Teacher Education Expert Panel recommended that “core content” be embedded in university ITE programmes, again with a big focus on how the brain works and learns.

The panel, chaired by University of Sydney vice-chancellor Mark Scott, was initiated by the previous right-of-centre Liberal-National government’s education minister, Alan Tudge. According to Monash’s Ellis, Tudge had conversations with UK ministers and “emulated the language of Gove and [former schools minister Nick] Gibb”. However, he says, this “flirting with the English ideas” was little more than “a bit of political theatre” tied to the country’s short election cycle.

The Australian Labor Party, back in power since 2022, has signalled some support for reform, but Ellis says it is unlikely to be as prescriptive and wide-ranging as that in England.

“The other big challenge for any federal Australian government is that you have got to keep the states on side,” he adds. “They control their own teacher registration systems. I don’t think what happens here will be anything like what is happening in England.”

Beryl Exley, a professor in the School of Education and Professional Studies at Queensland’s Griffith University, says some of the changes in Australia – such as the introduction in 2019 of the Teacher Performance Assessment (TPA), which assesses ITE students’ practical classroom skills before graduation – have generally been viewed positively by universities and schools. The introduction of payments for those on placements, as proposed by the recent Universities Accord, would also be welcomed, she says.

In the US, a similar dynamic between the states and the national government limits the ability of the federal Department of Education to introduce English-style changes. However, several right-leaning states have attempted to pass their own legislation.

In March, Florida’s Senate gave final approval to a bill that seeks to remove “identity politics” from teacher preparation programmes by restricting discussion of issues such as systemic racism in US institutions, a move the free speech organisation PEN America called a “gag order that muzzles professors on ideas and concepts” that could jeopardise “the integrity of higher education and the quality of K-12 instruction”.

Still, unlike England, both Australia and the US are seeing early signs that recruitment to ITE programmes has turned around. In the US, there was a 6 per cent increase last year, after several years of decline.

“In difficult economic times, people seem to be interested in a socially responsible job, making a difference, working with kids and helping them succeed,” says Ellis, who notes that enrolments in Victoria – where Monash is based – are “shooting up”, thanks to a return of domestic students supported by state government financial incentives, among other factors. “In other contexts, things are starting to turn around a bit, but they are not in England.”

And while the reason for England’s ongoing malaise is “probably not just one thing”, Ellis thinks the “turbulence” around delivery – after 14 years of ever-changing policy – is one factor. “If you get political figures saying, ‘Teacher education is terrible, and we are going to sort it out’, and if you are a prospective student, you’d say, ‘You sort it out [first], and I’ll become a teacher later.’”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login