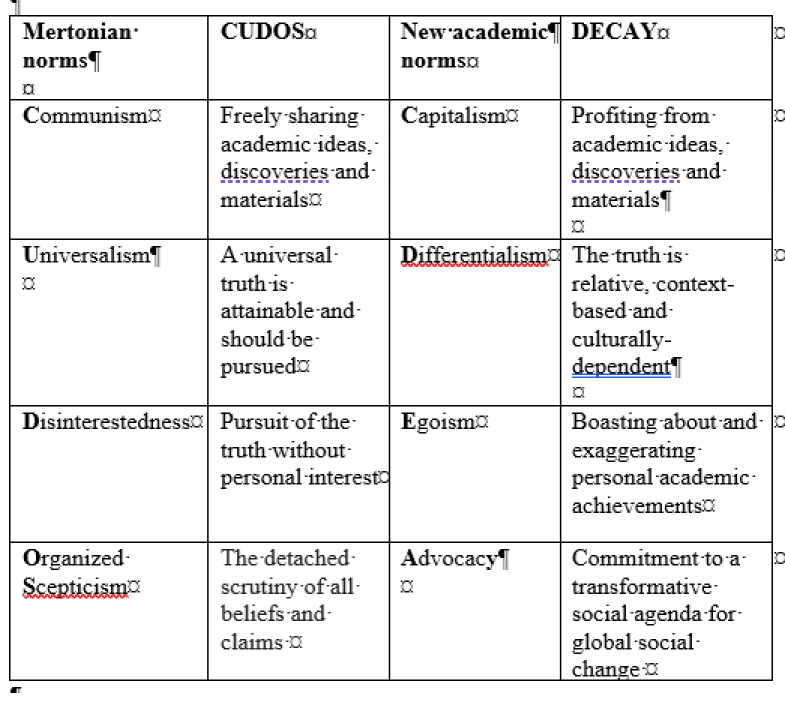

Back in 1942, the American sociologist Robert Merton set out a series of values that, in his view, represented what it means to be a good academic. These norms – communism, universalism, disinterestedness and organised scepticism – are widely known by the acronym CUDOS.

The word communism carried a lot of radical chic in the 1930s and ’40s, but Merton was really referring to the essentially liberal ideal of freely sharing ideas, discoveries and materials in the best interests of scientific advance, rather than anything overtly political.

Universalism implied that academics should pursue the truth uninhibited by racially divisive policies, such as those that Nazi Germany had institutionalised in the 1930s, while disinterestedness meant disentangling emotion and personal interests from research. Finally, Merton argued that it was crucial that academics scrutinised all beliefs and claims, however sacred, calling this idea organised scepticism.

Eighty years on, commitment to CUDOS among academics remains strong. But a very different institutional ethos has taken hold in universities around the world. And while Merton feared the way in which the totalitarian state threatened CUDOS, its modern corruption has been led as much by the university itself as by illiberal governments or other external forces.

Communism has been converted into capitalism. Universities actively encourage academics to monetise their ideas and discoveries rather than sharing them for public benefit. Phrases like “applied research” and “knowledge transfer” have taken a firm hold.

Nor is it any longer politically correct for an academic to say that they are pursuing a universal truth. The triumph of cultural relativism means that it is only acceptable, especially for social scientists, to qualify everything in terms of differentialism. Virtue signalling the context-laden nature of any knowledge claim is essential to avoid accusations of essentialism or post-colonial arrogance.

Then there is the displacement of disinterestedness with egoism. Boastfulness has become an academic virtue and many universities around the world have fallen under the spell of bibliometrics, encouraging their academics to represent their work as a series of proxy boasts about the size of their h-index, citation count and the impact factors of the journals they publish in.

Indeed, bibliometrics have become so powerfully seductive that many academics now seem either unwilling or unable to articulate what contribution to knowledge they are making. As egoism takes over the collective academic psyche, especially where I work in Hong Kong, we are losing touch with what is really important.

As for organised scepticism, even this enlightenment virtue is being turned on its head as universities replace a commitment to critically interrogating knowledge claims with social advocacy. The trend for large-scale interdisciplinarity has been hijacked as a marketing tool for universities to brag about their achievements in addressing the world’s problems. Not every academic wants to be an activist for global social change even though there is a place for individual activism. Sanctifying such an agenda as a piece of corporate branding poses serious risks for the historic role of the university as society’s interrogator-in-chief.

If we take a slight liberty in moving around the order of the initials of differentialism, egoism and capitalism and use both the first and last letter of advocacy, we get DECAY, an apt acronym to represent the degeneration of CUDOS.

Many academics now find themselves, like the Roman god Janus, facing two ways at the same time. They still believe in CUDOS, but they need to practise a wholly contradictory and corrosive ethos (DECAY) in order to make and sustain a successful career.

It is important to challenge and resist the perverse virtues of DECAY wherever possible. A glimmer of hope is represented by initiatives such as the Leiden manifesto and the Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA) which oppose the use of journal impact factors in research evaluation. Enlightened universities have signed up to such accords, but they cut little ice in East Asia.

Until this attitude changes, true academic values will continue to be corroded by the very institutions that ought to be championing them.

Bruce Macfarlane is chair professor of educational leadership at the Education University of Hong Kong. His paper, “The DECAY of Merton’s scientific norms and the new academic ethos” is published by Oxford Review of Education.