Companies were once trusted to provide the pensions they promised. That trust was broken in the UK with the revelation in 1991 that newspaper tycoon Robert Maxwell had looted the Mirror Group pension fund, and regulatory control has been progressively tightened since the 1995 Pensions Act.

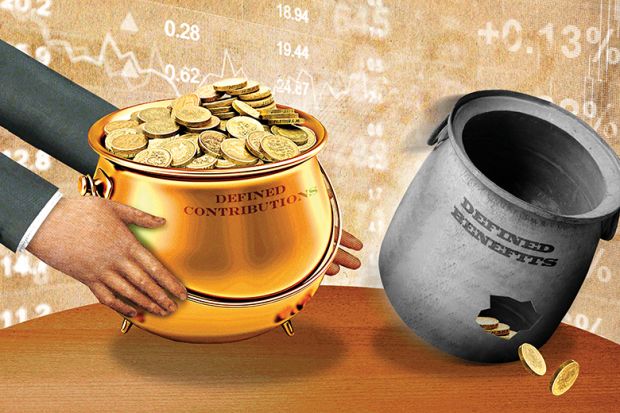

That legislation was intended to provide employees with complete security that their pensions were safe, whatever happened to their employers. But while the operation was a success, the patient died: defined benefit schemes are defunct unless underwritten by the taxpayer.

The problem is twofold. Employers struggle to afford the cost of guaranteeing that the benefits promised in 50 years’ time will be paid, come what may. Employees are also hit, though, because everyone ends up paying over the odds.

The basic equation is simple enough: contributions plus investment income equals benefits. Contributions – and even benefits – are fairly predictable, albeit affected by changes in life expectancy. The challenge is to estimate real returns on investment over several decades.

The regulator expects pension funds to play safe. In all probability, current contributions are sufficient to pay for the promised benefits, but the Universities Superannuation Scheme is obliged to be more cautious. As a result, some groups – including the University and College Union – have proposed that universities and staff should pay more for reduced benefits.

But defending defined benefits at all costs is a mistake. If contributions exceed the best estimate of what will be needed to pay future benefits, defined contribution schemes provide better value.

Whether defined benefit or defined contribution, pension funds are invested in the global markets. If the schemes are self-sustaining, as intended, the total amount available for distribution is the same under either arrangement. How that sum is distributed differs: dying soon after retirement is a bad move with defined benefits.

But the key feature of defined benefit schemes is that the employer underwrites the benefits, enhancing confidence about income in retirement. Changing from defined benefit to defined contribution involves a transfer of risk to employees.

Staff were right to reject such a move with no compensation. Increasing the employer contributions, however, could make it a fair exchange. If employers paid 15 per cent of salary into a defined contribution scheme, rather than the 13.25 per cent they offered in January, the fund available on retirement would almost certainly provide an income exceeding the defined benefit pensions now proposed.

In order to stabilise the USS’ finances, the UCU has proposed to reduce the annual accrual rate (the fraction of salary to be paid as a pension) from 1/75 to 1/80, while also raising total contributions. But if the union is correct in its argument that the current scheme is not underfunded, members would thereby pay too much for too little. A substantial proportion of the employer contribution would be earmarked to cover the estimated deficit.

With defined contribution schemes, you receive what you and your employer contributed over your working life, augmented by investment returns. With defined benefit schemes, you receive more or less than that amount, depending on when you worked and when you die.

Consider two academics, one aged 30 and the other nearing retirement. For a given salary below the defined benefit cap, they generate the same benefit from a year’s work. Their situations are very different, however. A little arithmetic shows that for the older academic, the defined benefit is a windfall: he receives substantially more than his current contribution would support. For the 30-year-old, though, it is very poor value. She could conservatively expect her contributions to grow by 2 per cent per annum, thereby doubling her money by age 65. This fund would be worth more than the defined benefits.

If we should regard employer contributions as deferred salary, as some have argued, that means early career academics (a substantial proportion of whom are women) are paying for liabilities already incurred by academics nearing retirement (most of whom are men). They will pay too much now and in the immediate future, only to see – in all likelihood – defined benefits end before the balance shifts in their favour.

Defined contributions would remain under USS management but staff would be able to choose investment funds based on their tolerance for risk and their ethical or religious preferences. Investment returns are uncertain, but over a period of decades there is little exposure to short-term fluctuations. Defined contribution funds also offer far more flexibility in how and when to use pension pots. You can choose to buy an annuity (and hence obtain a defined benefit pension) or draw out variable amounts over time.

The combination of low interest rates, low estimates of investment returns and low tolerance of risk by the regulatory authorities has torpedoed the attractiveness of defined benefits. These schemes have become poor value for younger staff. And they are the people whose pensions we should primarily be aiming to defend – not those of us nearing retirement with secure incomes.

David Voas is head of the department of social science at the UCL Institute of Education.

后记

Print headline: ‘Defending the USS defined benefits at all costs is a mistake’