The 16th-century Italian writer Giovanni Botero hypothesised that population growth reached a natural ceiling as “the fruits of the earth, from which people must draw their sustenance, cannot feed a greater number”. In early 17th-century England, Arthur Standish decried “the general destruction and waste of woods in this kingdom”, warning “no wood, no kingdom”. It can be tempting to read such statements as an awakening of modern environmentalist sensibilities: recognitions of the limits on natural resources and the need to adjust behaviour to use these more responsibly.

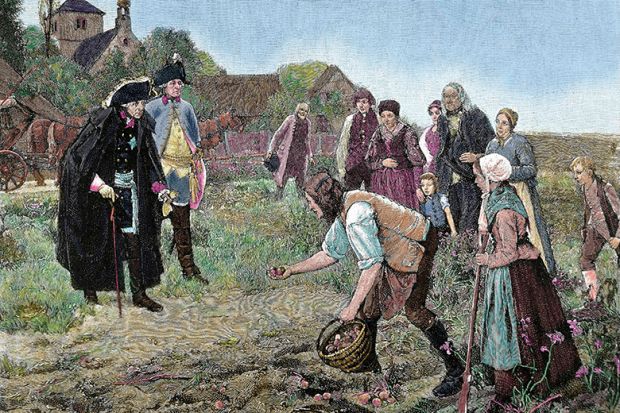

Paul Warde’s impressive study of more than three centuries of ideas about economic growth and agricultural productivity draws out a more complex story. Tracking debates and developments across various European countries – with a few excursions across the Atlantic – The Invention of Sustainability explores the ebbs and flows in ambitions to increase yields and the growing efforts to deploy scientific understanding to the challenge of how to draw more extensively on “the fruits of the earth”.

Forestry was an area of the economy where questions about the health of natural resources were readily linked to the fortunes of the community. Trees yield timber for future generations, presenting an unusual example of cultivation for which land management always had to take the long view. However, issues about the extent of the land used for food production, best practices in farming and the balance between urban and rural populations meant that states often took an active interest in how land was being used, what was being grown, where and how. Warde pays particular attention to the influence of the “cameralist” tradition in Germany and Sweden, which by the late 18th century provided a driver for academic studies into achieving greater prosperity and the best use of land.

Optimistic ideas about “improvement” had gained prominence during the 17th century, from Gervase Markham’s 1613 prescription for “the inriching of all sorts of barren and sterill grounds in our kingdome, to be as fruitfull in all manner of graine, pulse and grasse as the best grounds whatsoeuer”, to Walter Blith’s wonderfully titled The English Improver Improved (1652). Yet Warde points out that a key limitation in this period was that there was little understanding of how plants grew, or of the soil itself. The later sections of the book explore the growing interest in ideas about circulation being applied to agriculture, as to other aspects of the economy, and in the crucial impact of developments in chemistry: the knowledge that the pioneering German scientist Justus Liebig predicted in the 1830s “might produce a revolution”.

When the much-travelled American senator George Perkins Marsh published Man and Nature in 1864, he offered a seemingly prophetic warning about a future of “impoverished productiveness”, furnishing a canonical text for later conservationists and environmentalists.

But one theme that runs throughout The Invention of Sustainability is the difficulty of pinning down the meaning of “sustainability” itself, whether in the past or in the present. Warde articulates the problems faced by so much environmental history: the dangers of taking current analyses for granted as obvious truths, and then looking for revelations of this knowledge in the historical record. His own account, scholarly and nuanced, avoids any such temptations: a history of ideas that is always conscious of context, of the practicalities faced by those who worked the land and of the political challenges of managing access to these resources.

Clare Griffiths is professor of modern history at Cardiff University.

The Invention of Sustainability: Nature and Destiny, c. 1500-1870

By Paul Warde

Cambridge University Press

416pp, £34.99

ISBN 9781107151147

Published 12 July 2018

后记

Print headline: Fruits of the earth: a history