"Conservative students are preparing to test the effectiveness of the new freedom of speech legislation by fielding controversial visiting speakers at university…society meetings…The National Union of Students remains committed to its ‘no-platform’ policy which defends the right of a student union to refuse a hearing to speakers on strictly racist or fascist grounds.”

That is a passage that could have been written this week, about the latest clash between advocates of free speech (usually for right-wing speakers) and left-wing student activists unwilling to give them a forum to air their views. In fact, it was written 30 years ago. The story, “Tories’ free speech test alarms NUS”, features in the 31 July 1987 edition of what was then known as the Times Higher Education Supplement.

It is an illustration of the fact that although those involved in higher education policy debates have a sense that things are moving on, the movement is not necessarily as comprehensive or as linear as it might appear at the time.

To test how much the arguments in higher education ever really move on, we pulled from the archives our July editions from 45, 40, 35, 30, 25, 20, 15, 10 and five years ago. Would an edition of the THES from 1971 – the year that the supplement was launched by The Times newspaper – look like a dispatch from an alien planet, or just a slightly distorted version of the present planet Earth? And what would that say about the sector and its policymakers?

The answer is probably somewhere in between. There is certainly a great deal in those old editions that now looks very dated. Take the 1972 story noting that “computer-aided instruction is an educational technology comparatively new to Britain, and has yet to prove its worth” (“Exploring the potential of learning with a computer”, 7 July 1972). It is hard to imagine university teaching today without the use of technology. But one quoted academic does not see “the computer in the role of expositor within the foreseeable future” – and, for all the recent advances in artificial intelligence, many people would make a similar comment today. The present-day debates over the effectiveness of flipped classrooms and massive open online courses are also indicative of the uncertainty many universities still feel about how best to incorporate technology into their teaching.

Recurring worries about the paucity of computer science students being trained also sound very familiar. In some cases, student reluctance has been the issue, but in others it has been universities’ capacity to meet the demand. In 1982, for instance, Ove Nathan, then rector of the University of Copenhagen, noted the shortage of computer science specialists in industry and lamented the fact that his institution lacked the money and teachers to provide the majors in datology that a fifth of natural science students at his institution aspired to (“Computer science proves too popular”, 9 July 1982).

These statements were echoed by Eric Schmidt, the former chief executive of Google, 34 years later, in relation to the UK. He told a conference at the London School of Economics last year that the UK would need an extra 10,000 computer science academics if it was to keep up with the leading countries in the field.

“There is a computer science crisis in the country but it’s a crisis of opportunity. You’re missing the people to fix this quick,” he said.

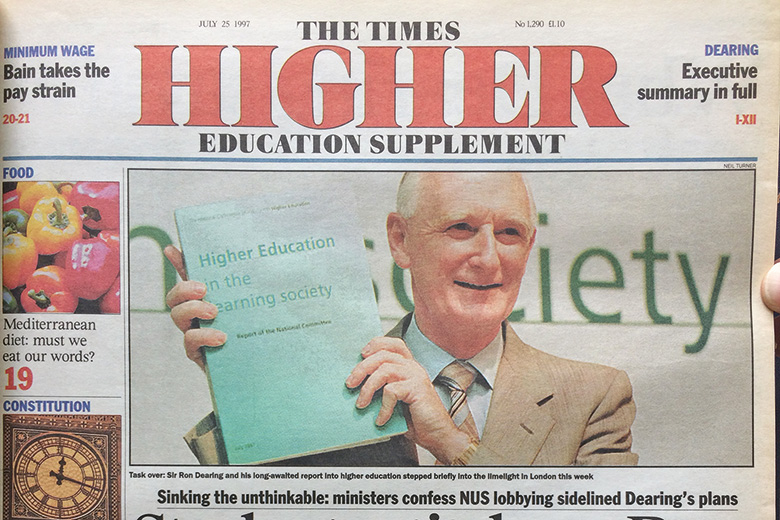

A particularly salient running theme over the decades concerns the rights and wrongs of student fees. In the UK, these were introduced for domestic undergraduates by the Labour government in 1998, having been recommended in the previous July’s Dearing Report.

Modern students facing annual fees of £9,000 a year may smile at the controversy over tuition fees of up to a mere £1,000, but the THES report of the time (“Students stitch up Ron”) reveals that it could have been worse if the government had not rejected the committee’s recommendation that all students be required to pay the fee regardless of parental income.

The report paved the way for a higher education funding system that has since remained in essence unchanged – except for the size of the loan students are required to take out. But the revival of the debate over tuition fees brought about by the electoral popularity of Labour’s pledge to abolish them will no doubt make forthcoming editions of THE look oddly familiar to those old enough to remember the Dearing days.

One issue surrounding tuition fees is their effect on student behaviour, with many academics concerned that students will start to act like consumers buying a service. This has been a worry about international students since 1980, when the Thatcher government began charging them “full-cost” fees. A 1987 opinion piece by Alastair Niven, assistant director general of the Association of Commonwealth Universities, encapsulates the concern: “Like any customer, [overseas students] won’t recommend the service if it has not satisfied them and they may even do the equivalent of walking out of a restaurant halfway through the meal if they think the courses they have ordered are not good enough.

“It is taking some institutions a long time to realise that a fundamentally changed relationship with their overseas students has come about and that it is no longer possible to assume that because at the end of the day the qualification on offer is British nothing else will matter” (“Home truths from abroad”, 3 July 1987).

A consumerist unhappiness with services rendered might be at least partly responsible for the rise in non-payment of fees by home students. By 2002, this had become a big issue, with many universities refusing to allow students to graduate until they coughed up (“‘No fee, no degree’ threat”, below).

Meanwhile, in 2007 (the year before the THES was relaunched in a magazine format as Times Higher Education), a proposal was made by “senior university administrators” to limit students’ rights to seek compensation for inadequate teaching (“Move to curb student rights”, below). But, as the article noted, the proposal “runs contrary to a new Government drive to put student rights at the heart of its new agenda”. The government at the time, of course, was Labour, but that ethos was taken up by its Conservative successor, culminating in the launch of the teaching excellence framework earlier this year.

Another aspect of the student-centred approach is the establishment of clearer and more robust complaints procedures. The UK’s Office for the Independent Adjudicator was established in 2003; prior to that, the last resort for students unhappy with universities’ handling of their complaints was the university’s external “visitor”: often a senior clerical or judicial figure. Even before domestic fees were introduced, there were concerns that such figures could “expose institutions to legal challenge” if they delegated their adjudicatory powers given that students were becoming “increasingly litigious” (“Lawyers warn archbishop on visiting rights”, below).

However, universities inundated with student complaints may find some solace in an article from 1972, in which an academic claims that confrontations in universities are engineered by people with immature attitudes to authority, stemming from their relationships with their parents.

“I am alternately amused and dismayed by the students and sometimes staff (who ought I believe to know better) who wish to diminish the authority of heads of departments and deans and principals and everyone else in the hope that somehow everything will get better,” Sir Michael Swann, then vice-chancellor of the University of Edinburgh, was quoted as saying (“Confrontation provoked by students ‘with immature attitudes’”, 7 July 1972).

He added that a key challenge for universities would be to strike a successful balance between democracy and authoritarianism: “Universities that draw ever more people into the so-called decision-making process, or alternatively stick to old authoritarian methods, will stick in the mud of mediocrity,” he said. It is a balance that many universities are still struggling to get right.

One area in which the sector has evolved enormously over the past five decades is internationalisation.

The principal focus of early editions of the THES on the UK reflects the fact that while research has always been very international, student and academic flows across borders were much smaller than they are today. Editions from the 1970s include stories on international students but, otherwise, what overseas news reports there were tended to focus on interesting developments in other parts of the world. There was little sign of the types of collaborations that are now commonplace between higher education institutions across the world.

However, there are some stark similarities between attitudes to internationalisation now and 30 years ago. Concerns over UK students’ unwillingness to study abroad seem particularly familiar. John Reilly, then director of the UK Socrates-Erasmus Council, which aimed to increase student mobility within Europe, wrote in 1997 about the significant decline in UK students participating in the pan-European Erasmus student mobility programme. He attributed it in part to inadequate foreign language training and a possible “climate of Euro-scepticism and uncertainty about the European future” (“Stay-at-home Brits lose us Euro edge”, 4 July 1997).

An element of Euroscepticism was also in evidence in a story from five years ago noting that the British government’s efforts to have the overall European Union budget significantly reduced could scupper lobbying efforts, supported by the UK academy, to see EU research spending increased during the forthcoming 2014-2020 budget period. “The UK – whose academy benefits from more EU research funding than any other member state – is one of the eight nations pushing to slash the main budget submitted by the European Commission,” the story reports (“Euro ‘own goal’? Coalition tactic could bleed British R&D”, below).

In the event, the proposed Horizon 2020 budget survived, but this could be the last framework programme the UK participates in given the country’s vote to leave the EU last year. Meanwhile, numbers of UK students studying abroad are still low, with just 6.6 per cent of full-time undergraduates undertaking international placements in 2014. Earlier this year, Universities UK International’s UK Strategy for Outward Mobility campaign announced a target to increase this figure to 13.2 per cent by 2020.

News reports from the 1980s and 1990s demonstrate that a push for UK universities to attract international students in order to boost their revenues have also long been in evidence. In 1987, Alastair Niven also warned: “Now that universities and colleges are being driven by financial need to market their wares abroad and to attract as many overseas students as possible they are having to wake up to the need to provide suitable welfare services, living conditions and, of course, academic guidance for the people whose high fees they are receiving.”

Meanwhile, an article published 10 years later, by a reporter in Melbourne, features concerns from a vice-chancellor at an Australian university that the poaching of foreign fee-paying students by other universities in his country could damage an export industry then worth A$3 billion (£1.8 billion) a year to Australia (it is worth A$20 billion today). Lauchlan Chipman, who led Central Queensland University between 1996 and 2001, said that some foreign students at his institution had been approached by agents offering them up to A$500 if they agreed to change university – and even more if they persuaded others to switch as well (“Plea to ban poaching of students”, 11 July 1997).

It is particularly interesting to note the large numbers of international students at some UK polytechnics as far back as the 1970s. A front page story in 1977 (“Sharp rise in poly applicants from overseas”, below) notes that more than half of that year’s 7,500 applicants to Oxford Polytechnic (now known as Oxford Brookes University) were from abroad – figures that many leading UK universities would be envious of today.

Another theme of the past few decades has been the increasing regulation of universities. The TEF may be the most recent imposition, but, in the UK, the roots of this go back as far as 1986 with the inaugural research selectivity exercise, the forerunner of the research excellence framework, which ushered in the era of performance-related research funding.

The fact that such exercises are often loathed by academics is partly due to the fact that their jobs depend on how they perform in them. UK academics are now easier to dismiss than they were prior to 1988, when the Thatcher government abolished tenure: a move that some universities were already pre-empting the previous year (“Tenure under siege on two fronts”, below). This means that academics are now much more beholden to their seniors than they once were: perhaps explaining THE readers’ continuing fascination with the peccadilloes of university leaders. Witness, for instance, the story from 2002 about vice-chancellors’ decision to charter a train to the Universities UK conference because the standard service did not have a first-class carriage (“The train on platform 1 is not posh enough”, below). Or the bizarre tale from five years ago about the registrar who left Durham University shortly after writing a blog in which she likened vice-chancellors to Miss Piggy (“This ‘Miss Piggy’ poster stays home”, below).

But “audit culture” has always attracted a lot of criticism in its own right, too. Ten years ago, Paul Ramsden, then chief executive of the Higher Education Academy, was quoted as saying that it risked driving teaching into “uniformity and monotony” and damaging student learning. “If I could be granted one wish to improve UK higher education, it would be to remove completely the apparatus of control and command and ‘we know what’s best for you’ that stifles innovation and consumes academic time in trivialities,” he said (“Good teaching stifled by audit, HEA head says”, 6 July 2007). Five years earlier, Stephen Prickett, then visiting professor at Duke University and author of Education! Education! Education!: Managerial Ethics and the Law of Unintended Consequences, had said something similar: “Monitoring education too closely, like monitoring particles in quantum physics, changes what is being examined. British education is being systematically corrupted by its own testing systems” (“Corruption of quality”, 5 July 2002).

The reason why university managers put such pressure on academics to dance to the auditor’s tune is that universities rely heavily on income from fees and government grants, the levels of which are affected by exercises such as the TEF and the REF. One potential way for universities to loosen the straitjacket and diversify their income streams is to work more closely with industry. Indeed, governments tend to be very keen on this idea, and often assert that universities are not doing a good enough job of translating their research discoveries into useful and lucrative products and services.

Academics, however, have sometimes felt that involvement with industry is rather grubby given companies’ short-termism, insistence on commercial confidentiality and exclusive interest in the kind of near-to-market research that earns few academic brownie points.

In a 1987 opinion piece, Kenneth Baker, Margaret Thatcher’s secretary of state for education and science, noted that many firms were also “suspicious” of the higher education system in general, following the “rebuff of earlier offers of help or requests for support” (“Market gardening”, 3 July 1987). However, Baker insisted that market forces and quality education were not “irreconcilable opposites”. Closer collaboration with industry, he said, would allow university staff to gain breadth of experience and expertise, keep up-to-date with the latest developments and obtain access to equipment and other resources. Meanwhile, companies would benefit from research and consultancy services, and students would gain from their teachers’ updated knowledge.

His conclusion is somewhat prescient: “Should our successors ever stumble across this article in the archives,” he wrote, “I feel confident that they will be astonished to read that there was a time when these things still needed to be said.” But while university collaboration with industry may currently be in the ascendant, it would be hard to conclude from this journey through the THE archives that Baker’s points will never need to be made again.

The 1970s and 1980s: overseas applicants, bugged meetings, the end of tenure, and free speech

40 years ago

Sharp rise in poly applicants from overseas (1 July 1977)

Applicants from overseas students to polytechnics have risen dramatically this year, particularly in engineering, despite the increase in tuition fees.

Figures released this week by polytechnics, including Sheffield, Oxford, Preston, Portsmouth, Leeds, Newcastle and Manchester, show that at some colleges between 30 and 50 per cent of applications for next autumn are from overseas.

The number of students seeking places from the “oil rich” countries has reached a new high level.

The increase in demand for engineering and science places follows the trend of last year but the significant proportion of applicants from overseas was unexpected.

Oxford Polytechnic said this week that more than 50 per cent of the college’s 7,500 applicants this year were from abroad.

In other news…

Police called in on Sussex ‘bugging’ (15 July 1977)

Evidence that Sussex University is considering stricter academic discipline has emerged from secret recordings – bugging – of a meeting last week of the students’ progress committee, the body which deals with academic performance, in one of the university committee rooms. The police have been called in to discover who is responsible.

The committee, which includes the vice-chancellor and deans of the schools, had been in discussion for some three hours when the hidden transmitter was noticed. One of the members spotted it in a pelmet over a window as he leaned back in his chair. The home-made transmitter was concealed in a tobacco tin connected by wires to a microphone and aerial.

30 years ago

Tenure under siege on two fronts (3 July 1987)

Two universities are pre-empting Government legislation by taking their own steps to abolish tenure. If they are successful, others may follow suit.

Both Surrey University and the University College of Swansea [now Swansea University] made moves this week to abolish or by-pass cast iron agreements on tenure written into their charters. They take the view that financial pressures will not allow them to wait for a bill to go through Parliament.

Ministers remain determined to fulfil a long-standing commitment to abolish tenure when legislation on the full range of state education provision is introduced in the autumn.

In other news…

Tories’ free speech test alarms NUS (31 July 1987)

Conservative students are preparing to test the effectiveness of the new freedom of speech legislation by fielding controversial visiting speakers at university and polytechnic society meetings.

The National Union of Students this week condemned any staged attempts to test the law as “provocative”. NUS president Ms Vicky Phillips said: “These tactics are designed to bring student unions into disrepute. Inviting speakers like John Carlisle, whose outspoken views already receive a lot of publicity, is the sort of antic we have been expecting.”

Mr Carlisle, the Conservative MP for Luton North, who supports sporting and other links with South Africa, and who was the target of student demonstration in several institutions last year, has confirmed his receipt of “two or three” invitations to speak at universities in the autumn term. He has not yet decided whether to accept.

The central Conservative student body – the Conservative Collegiate Forum – will be keeping a close eye on proceedings. A CCF spokesman said: “Given that we do not view controversial speakers in the same light as some students do, we will be fielding speakers on the basis that students have the right of access to them.”…

The NUS remains committed to its “no-platform” policy which defends the right of a student union to refuse a hearing to speakers on strictly racist or fascist grounds.

The 1990s and early noughties: A deal with students, high-profile visitors, non-payment of fees, and travelling with hoi polloi

20 years ago

Students stitch up Ron (25 July 1997)

Ministers have admitted that they made a deal with the National Union of Students to soften key funding options put forward by Sir Ron Dearing’s committee of inquiry, which published its report this week.

The Government has retreated from its earlier call for Sir Ron to “think the unthinkable” on raising more cash for higher education. It has rejected the report’s recommendation that all fulltime students should make a £1,000 a year contribution to tuition fees.

Instead, ministers have decided the amount of fee students have to pay will be means-tested, so that the poorest pay nothing while the wealthiest will have to find the full £1,000.

Well-off students will be entitled to extra loans equivalent to the fee they pay, so that their parents do not have to contribute more.

The Government also says it intends to axe maintenance grants, ignoring Dearing’s proposals to keep them so that poorer students would not be deterred from entering higher education.

Students who would have been entitled to grants will instead gain access to a loan as big as the current grant plus a loan maintenance package.

In other news…

Lawyers warn archbishop on visiting rights (11 July 1997)

High-profile university visitors, including the Archbishop of Canterbury and the Lord Chancellor, may expose institutions to legal challenges from students by delegating their powers, lawyers have warned.

The education law firm Mills and Reeve has received requests for help from a number of universities wanting to ensure busy visitors are pulling their weight. They are concerned that students, who are becoming increasingly litigious, may challenge decisions taken by visitors who have delegated decision-making.

Every chartered university in England has a visitor or board of visitors…They have widespread powers…to rule on appeals from students against an institution.

It is their job to ensure that a university’s procedures have been followed properly and any decisions they make cannot be challenged by the courts, provided they have exercised their powers correctly.

15 years ago

‘No fee, no degree’ threat (5 July 2002)

A record number of students will be prevented from graduating this summer as universities introduce tough sanctions in response to non-payment of tuition fees.

A snapshot survey by the THES this week found that the worst hit institution, London Guildhall University [now part of London Metropolitan University], was owed £6 million in fees accrued over several years. The University of Central England [now Birmingham City University] is owed £1 million and many other institutions said they had substantial sums outstanding.

The National Union of Students said the practice of withholding final examination marks or barring student debtors from graduation ceremonies was unfair. …

Vice-chancellor [of Central England] Peter Knight said: “It is likely we will collect most of the money eventually but it is an enormous bureaucratic problem in having to constantly chase students and deal with problems of debt.”

In other news…

The train on platform 1 is not posh enough… (5 July 2002)

Universities UK is planning to charter train carriages to transport vice-chancellors to their annual residential meeting this September because the only public trains available do not have first-class accommodation.

In a letter to vice-chancellors this week, UUK explained that most of them were likely to have to travel to the University of Wales, Aberystwyth, via Birmingham, where trains and planes inter-connect. But “unfortunately there is no first-class travel” on any of the available trains.

The letter said: “It is proposed to charter train carriages for those attending the conference. This would enable members to complete their journey in the company of other members, and the carriages would be less crowded than ‘normal’ carriages.”…

One vice-chancellor who was less than enamoured with the plan said: “It is the end of civilisation as we know it. A vice-chancellor might meet a student, or even the press, if they travel in standard class.”

The late noughties and the current decade: restricting student rights, Queen’s English, research funding and Muppetry

10 years ago

Move to curb student rights (13 July 2007)

A legal contract that would restrict students’ rights to seek compensation over inadequate teaching has been prepared by senior university administrators, The Times Higher has learned.

The contract, drafted by commercial lawyers for the Association of Heads of University Administration (AHUA), would limit students’ rights to take legal action if a course changed or closed, or if promises made in prospectuses were not delivered.

The contract, written by Pinsent Masons, would also protect universities from any liability for disruption caused by lecturers’ industrial action. The National Union of Students has attacked it as one-sided.

The initiative runs contrary to a new Government drive to put student rights at the heart of its new agenda, reflecting mounting tensions about the rise of a “consumer culture” among fee-paying students.

In other news…

Lecturers lectured on Queen’s English (13 July 2007)

Academics are not renowned for their clear use of English, but managers at Queen’s University Belfast have become so concerned at the clumsy and impenetrable language of their staff that they have issued a language guidebook.

The booklet, A Way with Words, will help to ensure that staff say what they mean, according to vice-chancellor Peter Gregson.

Staff must distinguish between “may” and “can”, especially when writing to students, it stresses.

“Can applies to what is possible and may to what is permissible…therefore students can miss every tutorial on their course, but may not if tutorial attendance is a prerequisite for passing.”

5 years ago

Euro ‘own goal’? Coalition tactic could bleed British R&D (19 July 2012)

Efforts by the UK to curb rises to the overall European Union budget are threatening to cut the €80 billion (£63 billion) in EU research funding proposed for 2014 to 2020, Times Higher Education has learned.

The UK – whose academy benefits from more EU research funding than any other member state – is one of eight nations pushing to slash the main budget submitted by the European Commission.

Speaking at the Euroscience Open Forum in Dublin on 13 July, Máire Geoghegan-Quinn, the European research, innovation and science commissioner, said that maintaining the budget for Horizon 2020 – the EU’s next research funding programme – would be “very tough” as not every member state believed that the proposed €80 billion figure was justified.

“Even member states who themselves invest enormous amounts of money in research and innovation are part of a group [that wants] to reduce the overall [EU budget] by €100 billion,” Ms Geoghegan-Quinn told a briefing. “The temptation [to cut research] is there… because it looks like a soft target.”

In other news…

This ‘Miss Piggy’ poster stays home (12 July 2012)

A university registrar who wrote a blog post appearing to compare her vice-chancellor to Miss Piggy has stepped down, it has emerged.

Carolyn Fowler, the first woman to hold the senior administrative post at Durham University, left the university at the end of June, the institution confirmed.

Although it is unclear whether her departure was connected to the comment, Ms Fowler had been on leave for more than a month when her exit was confirmed. She has also removed the post from her blog durhamregistrar.wordpress.com.

The article on “the relationship between registrar and vice-chancellor” was posted in mid-April…The “ideal state” was “two professionals with shared values and common goals”, she wrote, but the reality “often feels rather more like Kermit to Miss Piggy”.

“Piggy, secure in her stardom and suffering not a moment of self-doubt, performs with single-minded determination regardless of whatever chaos might be going on around her,” the post continued.

“Meanwhile the Registrar-Kermit desperately tries to keep Piggy and everyone else happy at the same time, his only fixed point the knowledge that the show must go on.”

后记

Print headline: Times Gone By