I stood once at the centre of Asia, the furthest point from the sea on this planet. The great Yenisei River, sludgy with tumbled ice floes, had more than 2,000 miles to run to the Arctic Ocean, and south were the vast steppes trampled back and forth by nomadic people for hundreds of generations. The city itself, Kyzyl, was dropped on to the plains a century ago, a grid of roads at the end of which concrete abruptly gives way to flowing green. The central point is marked by a globe and pillar, prayer flags snapping in the wind, a place of Siberian mystery many days of conventional travel from the rest of the modern world.

In my hotel room with wooden balcony, and a mix of otherwise Buddhist and Soviet icons, was a single large painting. It depicted a tropical beach, a line of coconut palms leaning over the sandy shore, a cobalt sky and crumpled waves on the reef. Yet no one there had seen such a salty sea. The sea, in this way, has ended up in all our imaginations, regardless it seems of location.

At the seaside, things of mystery happen. Whales beach. Seals smile. Birds congeal with oil. People sit in deckchairs and consent to do nothing, and watch other people doing nothing. Our relationship with the sea – we of an island nation – is always changing. In North Norfolk, the cottages of former seamen have no windows facing the sea. Why look, they would have said, at waters that with great force we spend all our days and nights seeking to outwit? They will take us anyway. Meanwhile, the waters rise, the CO2 in the atmosphere passes 400 parts per million, and the waters rise further still. It could be that we are lost already.

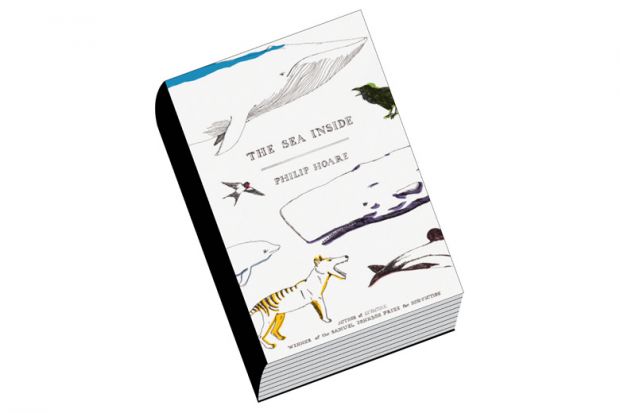

In The Sea Inside, Philip Hoare’s compelling journeys are in and over white, inland, azure, southern, wandering and silent seas. Inside the sea, Hoare reckons “the fixity of the sea and sky is a supreme deception”. His elegant essays weave alongside authors, scientists, monks: he travels with Darwin, five years in the HMS Beagle, a ship so unseaworthy as to be dubbed a coffin brig; with Thomas Merton and other hermits; with J. A. Baker of The Peregrine and Essex marshes fame; with T. H. White and the obscure island life that seemed to accentuate his peculiarities; with Tennyson, too; and Melville, of course. Whales feature prominently. Hoare stitches oyster-catchers into England’s shores, birds once prized in dishes such as sea pies, then seen as oyster-stealing pests and shot in great numbers until the 1960s. These longest living of waders (individuals can live 40 years or more) now describe the edge-seas of mud and lapping wavelets with piping echoes. The sea wanders under London, too, the Thames’ many tributaries bound and strangled and paved, but still flowing underground and salty with the tides. The Strand commemorates what was once a beach, and on old maps the names Temple Stairs, Surrey Stairs and Whitehall Stairs appear, all of them descents to the water.

Hoare swims with blue whales off Sri Lanka and watches humpbacks off Cape Cod. So little is known of cetaceans and their societies that any engagement is a mystery part revealed. “He is seldom seen,” observed Ishmael of the blue. Not surprising, given our remorseless harvesting: 40,000 blues were caught in the Southern Ocean in 1939 alone; so many hundreds of thousands killed that blue whale populations can never recover – they just do not meet enough. David Collins, the governor of Tasmania at the time, complained that the estuary at Hobart was so full of southern rights that it was almost too dangerous to navigate. They kept him awake at night with their huffing and blowing, he grumbled.

In water, noise travels faster and further than in air, and whales chatter. Sperm whales click, toothed whales beep sonar. If a sperm whale shouted as loud as it could, at more than 200 decibels, it would cause life-threatening harm to any whales nearby. They presumably know when to behave properly. Both whales and dolphins have enlarged amygdalae, the processing centre of brains that controls emotions and social connections. Hoare also swims with sperm whales in the Azores, in their blue world where beneath is utter darkness. Their sweet high-pitched song rises around him, he only 5ft 8ins and they 50 tonnes of flukes and fins and baleful eyes. The post-hunting population of sperm whales is estimated to be 360,000: there are 316 million sq km of ocean, nearly a thousand for each individual. He describes how two whales come head to head, touching brows and lolling in the water. In a cetacean crèche, adults deliberately caress and touch the youngsters, reassuring as we do with our children, too.

Yet the question of why whales beach remains deeply troubling. What do they know, that we do not? Hundreds, sometimes thousands beach themselves on the shores of New Zealand each year and are regarded as tapu, sacred signs. On one occasion, 59 stranded sperm whales were declared human and buried in a communal 500ft grave. People rush to the shores when they hear of such mass actions by the world’s largest animals, but do not know what to do. Recently, a Māori elder carried his sleeping bag to the shore to spend the night with a pod of pilot whales so that they would not die alone. Perhaps this is all we can do.

Hoare writes with passion too of birds. There are clever cliff corvids, able to call foxes or wolves to a dead animal to let them do the hard work; able in modern cities to put nuts on pedestrian crossings for cars to crack, and then wait for the red light to retrieve them. There is also the long-extinct moa, and the albatrosses that may spend a decade topside never touching land, becoming whiter as they age, tending towards Coleridge’s ghostly soul-bird. “God save thee, ancient Mariner!…with my cross-bow, I shot the albatross.” There are shearwaters wing-locked over oceans, nesting in burrows, diving to pick sand eels from the mouths of whales. Our language, though, remains rooted in land. We speak of whales and dolphins off Cape Cod, off Charlotte Sound. We are always on islands, not in them, just as if they were ships, ready to return to port one day.

I have walked far along a coast, let the water and light in, and salt encrust, let blisters invade, let the ebb and flow and the Moon and wind change every place. This seaside is a liminal zone, a place of uncertainty and of innovation, too. It’s the one place in the world that responds minute by minute to the pull of Earth’s satellite. Ecosystems mostly change by the day or week or month; the tidal coastline moves at a different pace. From space, our planet is clearly more blue than green. Arthur C. Clarke thought a better name for it would be Ocean.

At home, I have a crooked walking stick hewed from hedgerow ash by John Masefield. To me, Sea Fever captures simply the sea inside us all. Masefield wrote: “I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and the sky/…To the gull’s way and the whale’s way, where the wind’s like a whetted knife./And all I ask…and all I ask, is a/…Quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick’s over.”

The Sea Inside

By Philip Hoare

Fourth Estate, 384pp, £18.99 and £9.49

ISBN 9780007412112 and 12129 (e-book)

Published 6 June 2013

The author

Author, broadcaster, visiting fellow in English at the University of Southampton and Leverhulme artist-in-residence at Plymouth University’s Marine Institute, Philip Hoare confesses that he feels “a complete fraud as an academic. I really know nothing more than the students to whom I speak. But Southampton appear to have some kind of confidence in me, which is touching.

Author, broadcaster, visiting fellow in English at the University of Southampton and Leverhulme artist-in-residence at Plymouth University’s Marine Institute, Philip Hoare confesses that he feels “a complete fraud as an academic. I really know nothing more than the students to whom I speak. But Southampton appear to have some kind of confidence in me, which is touching.

“I’ve also just been teaching a short course of critical writing at the Royal College of Art, which has been incredibly rewarding, mostly on account of the students’ extraordinary imaginations and the breadth of their responses to the tasks I have set for them (although I must admit I also enjoyed the grand lunches in the legendary Senior Common Room).”

He adds: “Can you teach writing? All I can do is tell stories, really - some of them more believable than others. My academic colleagues are all so much cleverer than me that the sense of imposture is only underlined. I certainly enjoy their company, and that of the students. I think higher education - from my personal perspective and fitful professional experience of it up till now - has gone through some bad lows. At one point I’d despair of eliciting any reaction at all - let alone a creative one - from some classes I taught. But I think there’s a new attitude, partly as a result of the competing and expanding creative writing courses. I don’t totally agree with them, but I absolutely agree with what they try to do.”

Hoare lives “in a suburb of Southampton, in the house in which I grew up. It is a three-bedroom semi-detached house, built in 1921. It once held 11 members of my extended family. Now it holds only me.”

The coastal city “is not a place people visit for its own sake. It’s really only somewhere on the way to somewhere else. It has an extraordinary history - from Roman port to the Mayflower’s departure point, to the Titanic - and beyond. Yet it appears to have virtually no place in the national collective consciousness. It is as if its fluidity, as a port, seeks to erase its own past.”

He adds, “You can see why I like it.”

Had he the choice of living elsewhere, Hoare might well remain by the sea. “The place I most visit is Provincetown, on the tip of Cape Cod (also, coincidentally, the place where the Pilgrim Fathers made first landfall - a fact also conveniently forgotten in American history). I have many friends there, human, canine, and cetacean. It is a spit of sand held out into the Atlantic, surrounded on three sides by the sea. Thoreau said of it that a man could stand there ‘and put all America behind him’.

“It is where I was first introduced to whales in the wild, and where my friend and mentor, the naturalist Dennis Minsky, lives. As does the great poet, Mary Oliver, who has also become a friend. The house I stay in is owned by a wonderful artist, Pat de Groot. She built it in the mid-1960s, with her husband, an Abstract Expressionist painter, Nanno de Groot. I can virtually jump out of my bed and into the sea.”

He adds: “You can see why I like it.”

Reading came naturally to Hoare as a child. “My mother was only content if she had a book to read. My grandfather would miss his stop on the bus, he was so intent on reading his book on the upper deck.” It is unsurprising, given this legacy, that he too “read omnivorously, especially my set of Junior World encyclopaedias, which were published in the early 1960s and illustrated with colour pictures set within the text itself. I sometimes think that everything I have written since came from those 12 volumes, lined up in the wooden box my father made to contain them.

“I didn’t really play with other children as boy. Generally they didn’t interest me. I hated sports. I lived in my imagination. I loved the past. When I walked to school I’d imagine the history layered beneath the pavement beneath my feet, strata of other lives which I could somehow revive in my fervid mind. My father worked for a cable factory for 40 years. But every Saturday he took us out to the country or the beach, and we learned a lot about England, Wales and Scotland. Funnily enough we never went to Ireland - even though I am one-quarter Irish.”

“I owe much of my later education to David Bowie and punk rock,” he adds, “but that’s another story.”

Invited to reveal his hobbies, Hoare says: “The director John Waters, another of my mentors, always reacts with (not so) mock indignation when people ask if he has a hobby. There’s no such thing for a writer, I guess. Everything feeds. You might say my ‘hobby’ was swimming - which I do every day, in the sea, often before dawn, winter, spring, summer and autumn. It is hardly a hobby, still less a sport. I do it to leave the land and gravity behind. It is an obsession, rather than a pastime. Who has free time? There is no such luxury in the 21st century. We thought we would be freed by computers, but that has merely been manumission in reverse, a new enslavement. It is a given barely worth restating that we are in thrall to our devices and the security cameras and store cards that record our every move. For our own good, of course.”

Hoare’s broadcasting credits include writing and presenting the BBC Arena film The Hunt for Moby-Dick; he also directed three films for BBC’s Whale Night in 2008. Asked if he has any secrets on successful broadcasting for academics faced with the challenge of conveying complex ideas to a broad audience, he reiterates, “I just tell stories. If art is imagination acting on experience, I’m just the conduit between the things I experience or learn, and the audience that might find them interesting. If you find these things interesting enough yourself, and you remember what it was like to discover something for the first time, that is usually enough. Broadcasting is a very, very hard thing to do…to say something in so few words, and to sound convincing about it. I might get good at it one day.”

His first encounter with Herman Melville’s leviathan-sized novel Moby-Dick came just ten years ago. “It was only going to New England and discovering its history - which really does lie barely below the surface - that I had the context to understand Melville’s mad ambition. Seeing whales in the wild, too, made me realise what he was going on about.

“Then I realised how funny the book was. How subversive, too. I was hooked. It amazes me that high school students in the States are, or were, obliged to read the book. I’m not sure you can get it till you’ve lived a little. And how did their teachers explain chapters such as ‘The Cassock’ - which is devoted to the whale’s foreskin? (It strikes me as a little ironic, given that some US schools have banned Harry Potter).

His interest in this wonderful - but off-puttingly large - work is, he says, “one of the reasons why I co-curated, with the artist, Angela Cockayne, the Moby-Dick Big Read, as part of my stint as artist-in-residence at the Marine Institute at Plymouth University. Angela and I realised how many people were fascinated by the book, yet intimidated by its scale and reputation. So we commissioned 136 readers to read its 136 chapters, and put the results online, as a free-to-download digital rendition of the entire book.

“Each chapter is also accompanied by a work from a contemporary artist inspired by the book and its themes. It was amazing how disparate the cast list became - from Tilda Swinton to Stephen Fry and Benedict Cumberbatch, from a vicar, schoolchildren and fishermen, to Fiona Shaw, Blake Morrison, Simon Callow and the Prime Minister. We’re hoping to release it as an e-book, soon, too.”

As a biographer, Hoare has turned his attention not only to cetacean legends (2008’s award-winning Leviathan, or, The Whale) but to human ones. He is author of Serious Pleasures: The Life of Stephen Tennant (1990), Noel Coward: A Biography (1995) and Wilde’s Last Stand: Decadence, Conspiracy, and the First World War (1997).

Asked if he would consider confessing to a favourite among his subjects, he replies: “Stephen Tennant [1906-1987] was my first love, and one doesn’t forget that. His family tried to stop me writing his biography. They thought I was going to hold him up to ridicule. As if. I was obsessively in love with him. Or at least, what he represented. He was the epitome of decadence, with gold dust in his hair and Vaseline’d eyes, but he was also an intimate friend of E.M. Forster, Virginia Woolf and Willa Cather, and lover to Siegfried Sassoon.

“He painted and wrote a book, Lascar: A Story of the Maritime Boulevards, which he illustrated in ever-changing coloured inks and couldn’t bear to finish. When he got to the end, he just started at the beginning again. He lived an extraordinary Arts and Crafts manor house in Wiltshire, which he transformed into a simulacrum of his beloved South of France by having 22 tons of sand spread over the lawns, planting palm trees and letting tropical birds and lizards loose in the grounds. (In the winter they took refuge inside the house). There he became, latterly, a Miss Havisham-esque recluse, living on his memories. His sometime tenant was V.S. Naipaul, who wrote about Stephen in The Enigma of Arrival.

“Indeed, Stephen is a Zelig of 20th-century culture, having appeared as a character in Evelyn Waugh’s novels in the 1920s, in Woolf’s diaries and in his niece Emma Tennant’s novels. He was still being visited by Derek Jarman, David Hockney and Marie Helvin in the 1960s and 1970s. I followed in their footsteps, and met him in 1986. It was a visit that changed my life, since it prompted me to write my first book - an attempt to explain the effect of that memorable day.

“Caroline Blackwood, who knew Stephen when she was married to Lucian Freud, told me that Stephen was the nearest thing to David Bowie that the 1920s produced.”

He adds: “You can see why I liked him.”

Of the many references in British culture that suggest that the seaside is a mournful place, Hoare observes, “Isn’t the word ‘resort’ itself a mournful one? The last resort. Often the sea is just a reflection of our human state. We gaze at it, and see ourselves mirrored. Herman Melville writes evocatively of the city-dweller’s compunction to go to the water, to stand at the land’s edge - even if it were in the metropolis of Manhattan. ‘Nothing will content them but the extremest limit of the land. They must get just as nigh the water as they possibly can without falling in…As every one knows, meditation and water are wedded for ever’. That was important in a new industrial age, as was Melville’s, when life was being pushed further and further to the margins, even as the cities sucked it in.

“The sea is the last wilderness - yet (especially in this island nation) we are seldom far from it - in our minds, if not in reality. That sense of a border place, a liminal region, something in between - it is, after all, only liquid gas, and has no colour of its own, only what it reflects - utterly fascinates me. It makes me as happy as it makes me sad.

Asked if he sees those who live far from the sea as different in some essential way to those who dwell next to it, Hoare responds,

“Of course not. We are all 90 per cent water, anyway. It’s where we all came from. There is a magnetic pull to the sea whether you live in Coventry or Cornwall. Whenever you see it, the sight of the sea is recognition. It is freedom, disaster, beauty and death. As everyone knows. We are all wedded to it, forever. When I was a boy, another of my fantasies was to grow gills and be able to breathe underwater, inspired by a 1960s Japanese animated cartoon in which Marine Boy chewed oxy-gum and rode a dolphin.

He adds: “I’m still waiting for the oxy-gum.”

Karen Shook