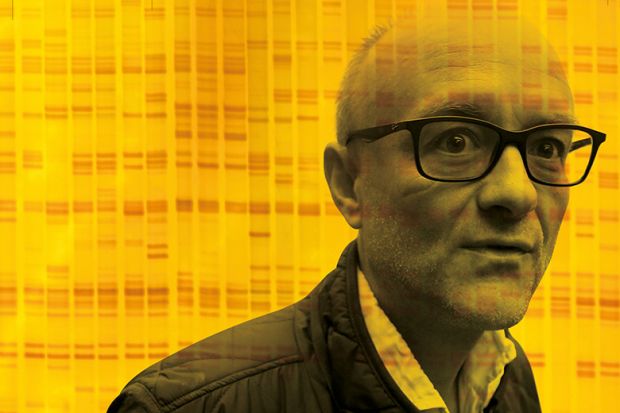

Since being appointed Boris Johnson’s most senior adviser in July, Dominic Cummings has made No 10, and himself, the critical forces on science policy in government, with a clear ultimate aim in view. “Dom’s dream is for the UK to become a global leader in scientific research and education, as well as the Silicon Valley of Europe,” Steve Hsu, a professor of theoretical physics at Michigan State University and a friend of Mr Cummings, told Times Higher Education.

Understanding Mr Cummings’ veneration for science takes us to the heart of his political vision for Brexit and how he hopes to radically change the country.

For anyone who has not shared in the UK media’s Cummings obsession, he is the former Department for Education special adviser who subsequently ran the Vote Leave campaign in the European Union referendum and created the slogan that cut through everything: “Take Back Control”. The copious blog that he wrote in his years outside government evidences that he is a passionate admirer of “brilliant scientists”, as Professor Hsu put it, particularly those whose discoveries led to disruptive technological breakthroughs.

If the Conservatives win the general election and deliver the major increase in science funding being discussed, Mr Cummings could have a huge amount of power over the future of UK research.

“It is clear he’s very interested in science as a potential driving force for a post-Brexit economy,” said Richard Jones, a professor of physics at the University of Sheffield and science policy analyst, who attended a recent meeting convened by Mr Cummings on the theme of creating a UK equivalent to the US’ Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa).

Some suggest that Mr Cummings has already deluged UK Research and Innovation, established by the government in 2018 to oversee the research budget and funding councils, with requests for strategy papers.

There are some in the sector who fear that the powerful adviser would seek to smash the buffers that separate government from decisions about which research to fund, breaching the conventions of the Haldane principle.

Is it simply a good thing for research to have a “friend to science” in a position of such influence? Or does Mr Cummings’ “scientist-as-hero” view, refracted through a “Californian ideology” on technology, misunderstand the nature of UK science, and the reasons why it has been so successful?

Soon after starting work at No 10, Mr Cummings made a sartorial science statement, wearing a Sci Foo T-shirt. His 2014 visit to Sci Foo, the invitation-only science conference held at Google headquarters in Mountain View, California, led him into a period of intense thinking about the role of science and technology in the UK’s future.

Sci Foo is “a sometimes uneasy transatlantic dialogue between American science and European science”, centred on “the power of technology to improve our lives, with much less thinking about whether everybody would agree with those improvements”, according to Jack Stilgoe, a senior lecturer in science and technology studies at UCL who has attended the event.

Mr Cummings wrote a blog entry on return from Sci Foo, detailing what he learned and the implications he derived. The University of Oxford history graduate wrote that “one of the few things the UK still has that is world class is Oxbridge” and “we have the example of Silicon Valley and our own history of post-1945 bungling to compare it with”, yet “we [the UK] persistently fail to develop venture capital-based hubs around Oxbridge on the scale they deserve”.

Mr Cummings was quick to try to start implementing his science and technology agenda in government, hosting a No 10 round-table event on promoting mathematics in universities with a number of prominent professors in August. Dorothy Bishop, a professor of developmental neuropsychology at Oxford, was among those invited, and she blogged about the meeting afterwards.

Mr Cummings stressed that he wanted to “help the mathematicians because he felt their pain as people that were subject to immense amounts of bureaucracy”, Professor Bishop told THE. There was some criticism from the professors about time spent on form-filling, which would be expected from all academics, she argued, “particularly if you’re a pure mathematician and you have to fill in a grant proposal and do a pathways to impact statement”.

At the meeting, Professor Bishop perceived “a sense in which it sounded like he [Mr Cummings] thought he could just bypass the normal routes to funding.

“Whereas we normally have…this buffer between government and universities, I think he was quite keen to take the view he wasn’t going to bother with any of that: that was all slow and bureaucratic. He could decide this was a good topic to fund and money would be found, and would bypass, probably, the research councils.”

Mr Cummings’ office issued the invitations to scientists for the meeting about the potential to create a UK Darpa, held at Downing Street on 25 September. The meeting was chaired by Chris Skidmore, the universities and science minister, with other attendees including the UKRI chief executive, Sir Mark Walport (who will retire next year), and the government chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance.

Darpa, set up by the US government in 1958, created the forerunner to the internet. Mr Cummings has often expressed admiration for the agency, writing in December 2014: “We should create a civilian version of Darpa aimed at high-risk/high-impact breakthroughs in areas like energy science and other fundamental areas such as quantum information and computing that clearly have world-changing potential.”

Mr Cummings’ enthusiasm for Darpa is based on “this view that if you apportion grants more entrepreneurially and give more discretion to very good people, better things will get done”, said Stian Westlake, a former adviser to three Conservative science ministers.

Asked whether he had any concerns about Mr Cummings’ vision for science funding, Professor Jones said it depended on whether new instruments are “limited scale” additional investments or a “radical reshaping of the entire system”.

Critics describe Mr Cummings’ particular understanding of science as relying on myth. After the prime minister’s adviser was pictured wearing the Sci Foo T-shirt, Dr Stilgoe tweeted that he “swallows the exhaust of technological determinism” and adopts a “Hollywood view of scientist-as-hero” that is a “terrible basis for policy”.

Dr Stilgoe told THE that he was moved to comment after seeing “a couple of UK science leaders expressing enthusiasm for Cummings being somebody who gets science”. He added: “My caution would be: be careful what you wish for. Because being ‘a friend of science’ isn’t a straightforward thing.”

The Cummings view of science is drenched in “the Californian ideology, a particular combination of libertarianism and technological optimism”, Dr Stilgoe argued. “My guess is that he’s more excited by Elon Musk than he is by Mark Walport. He’s more excited by the disruptive potential of science than he is by the massive institutional apparatus that is needed to keep a world-class science base functioning.”

There are many who would argue that Mr Cummings has already inflicted grave damage on UK science through his role as “mastermind of Brexit”, of course.

At the round-table with mathematicians, “he started out by saying that he didn’t think it would be helpful to discuss Brexit, so could we talk about other things”, said Professor Bishop.

The Vote Leave campaign’s statements on science from 2016 have the ring of Cummings. A Vote Leave open letter on science, signed by 13 Tory MPs including Boris Johnson, called the EU’s research programmes “unnecessarily bureaucratic”.

It continued: “As the Nobel Prize winner Andre Geim said: ‘I can offer no nice words for the EU framework programmes [for research] which…can be praised only by Europhobes for discrediting the whole idea of an effectively working Europe.’ After we vote leave, it should be a priority to increase funding for science and fix problems with the funding system, not all of which are the fault of the EU.”

The ellipsis in the quotation from Sir Andre’s Nobel lecture removed the words “except for the European Research Council”. The EU’s highly prestigious ERC – from which the UK is likely to be excluded under a no-deal Brexit – awarded grants of about £10 million to Sir Andre and Sir Konstantin Novoselov during their research leading to the discovery of graphene at the University of Manchester.

Mr Cummings may have a willed blind spot when it comes to the benefits UK science has gained from EU membership.

A separate Vote Leave briefing on science said that “if Britain takes back control of the money we send to Brussels and diverts some of it into science, we could make Britain a world leader in crucial fields”.

Rather than Mr Cummings’ enthusiasm for science being secondary to his enthusiasm for Brexit, he appears to see Brexit as the means to bring about the true flourishing of UK science.

Mr Westlake, who has spoken with the prime minister’s adviser since his appointment, said of Mr Cummings’ views on science: “Brexit provides the opportunity to overturn the way the government works, especially in relation to research and technology – and so is a necessary condition for more breakthrough innovation. I don’t think these views are some kind of disingenuous cover for Brexit on Dominic Cummings’ part; I think they are what he genuinely believes.”

Whether Mr Cummings finds himself in a position to implement his vision for a science- and tech-fuelled post-Brexit economy – perhaps one reliant on an Oxbridge Silicon Valley – will be decided by the next general election. That vision would pose huge questions: whether the line between breakthrough science and valuable start-ups is as linear as Mr Cummings assumes, and how such an economic model would deliver for all parts of the UK.

For now, science and research have a friend in the highest of places, one who is already powerfully flexing his hand of friendship.

后记

Print headline: Is great disrupter’s science vision born of fact or fiction?