See the top universities in the THE New Europe ranking

The Humboldt University of Berlin and the University of Warsaw could be twin institutions. Both can trace their history back to the 1810s, and both have educated some of their respective countries’ most celebrated political, artistic and scientific talents. Karl Marx and Otto von Bismarck attended the German institution, while Warsaw has produced five of Poland’s Nobel prizewinners, including the writers Henryk Sienkiewicz, author of Quo Vadis, and Czesław Miłosz, who confronted 20th-century totalitarianism through his poems and books.

Warsaw and the Humboldt even look somewhat similar: their historic city centre campuses are both characterised by cream-coloured Neoclassical buildings topped with Romanesque statues. After the Second World War, their political fates were entwined, too: both endured the heavy-handed control of communist governments before they emerged, blinking, into a post-communist world at the beginning of the 1990s.

Since then, however, their progress has been divergent. Rankings cannot measure all that a university does, but on their evidence, Warsaw, which sits in the 501-600 band in Times Higher Education’s latest World University Rankings, now lags a long way behind the Humboldt, which is at 62nd. Other measures also show that the Humboldt has become a more mature research university. Since the European Research Council was launched in 2007, Warsaw has won 13 of its hypercompetitive grants, but nine of these were starting grants, the most junior awards; only one was an advanced grant for well-established academics. Humboldt researchers, meanwhile, have won 14 ERC grants, of which six have been advanced.

This gap is symptomatic of the failure of Europe’s former communist nations to catch up with their western neighbours in the lab as quickly as had been hoped when the Iron Curtain was swept aside nearly three decades ago, despite the accession of nearly all those nations to the European Union.

In the economic sphere, many of the so-called EU13 countries – which all joined the EU since 2004 and also include Malta and Cyprus – are fast closing in on the West: in terms of purchasing power per capita, most former communist nations have made big strides; Czech and Slovenian citizens, for example, are now only fractionally poorer than the EU average, and they are better off than those in Portugal and Greece. Poles are also slightly better off than Greeks, according to 2016 figures from the World Bank on gross domestic product per capita, adjusted for purchasing-power parity, and Warsaw’s skyline is chock-full of gleaming new towers that make Berlin look provincial. Poland’s growth rate hit 4.6 per cent in 2017, an expansionary pace that western European politicians can only dream of.

But look at a map of research prowess, and the legacy of the Iron Curtain remains clear. The EU’s Regional Innovation Scoreboard for 2017 maps the proportion of papers that are highly cited in each European region. The old border between communism and capitalism is still clearly visible in the citation data, with the illuminating exception of former East Germany (plus, arguably, Slovenia and parts of the Czech Republic).

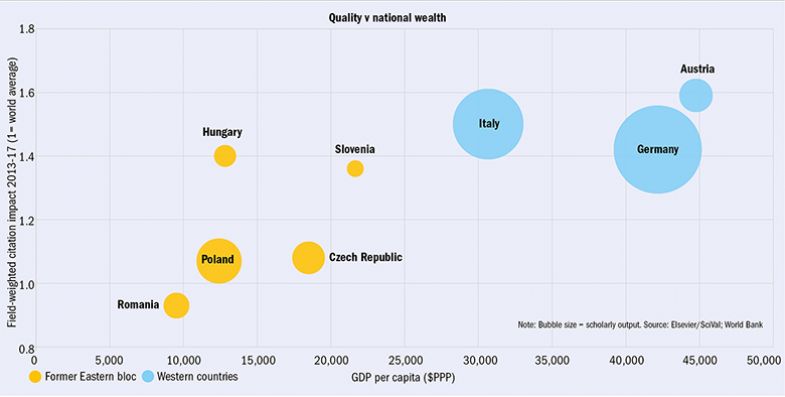

In terms of field-weighted citation impact, which accounts for disciplinary differences, Poland, Romania and the Czech Republic score well below neighbouring Austria, Germany and Italy; Hungary and Slovenia perform better but still lag behind Germany.

It can be argued that bibliometric data are retrospective given the time that it takes for citations to accrue, and thus might not capture the current picture, but a look at grant awards, which are prospective, tells a similar story. In 2015, the EU’s new eastern members won just 3 per cent of the ERC’s starting grants, according to “Scientific publication performance in post-communist countries: still lagging far behind”, a 2016 Scientometrics paper by Czech researchers that examined the lingering east-west gap. By comparison, the EU13 accounted for 8.7 per cent of the EU’s GDP in 2017.

Twin-track Europe: countries behind former Iron Curtain still held back

So why has the Humboldt – and the East German research system in general – managed to become “western” while Warsaw and Poland have remained “eastern”? And what do their stories tell us about the chances of the east of the continent catching up with the west any time soon?

After the Berlin Wall came down in 1989, “the transformation was more radical in East Germany than in the other eastern European countries”, explains Peer Pasternack, director of the Institute for Higher Education Research at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg, and an expert on post-communist university history.

In the former German Democratic Republic, institutes researching subjects that were considered politically compromised, such as philosophy and history, were shut down. Committees were set up to ascertain the political integrity of East German professors, checking their histories for evidence of collaboration with the Stasi, for example. About one in 10 Humboldt professors was dismissed for political reasons, according to Pasternack’s research. For instance, it turned out that the president of the Humboldt, the theologian Heinrich Fink, had been an informant.

But this was not the end of it. With few exceptions, East German professors had to reapply for their jobs, Pasternack explains, in competition with applicants from West Germany, where there was a “backlog” of junior researchers unable to get senior jobs. Particularly in the humanities, this resulted in East German academics losing their jobs to newcomers from the West.

By 1997, just 16 per cent of the Humboldt’s academic staff had been employed there since 1989, according to Pasternack’s research. The slate had been all but wiped clean.

Meanwhile, the former GDR’s research system was explicitly remodelled on West German lines. West German research institutions also moved east; the Max Planck Society, which since the Second World War had emerged as the Federal Republic’s leading network of institutes conducting basic research, set up 18 institutes in the former East Germany, and even moved its official headquarters to Berlin (although its true, administrative, headquarters remains in Munich).

Maciej Duszczyk, now Warsaw’s vice-rector for research and international relations, was based in Leipzig for six months in 1992. He recalls East German professors losing their jobs and being replaced by researchers from the West. In Poland, however, it was “absolutely impossible” to follow the same path, he says, because, of course, there was no West Poland to supply researchers.

Nor was there any West Poland to inject funding into the former communist state. By 2014, it was estimated that West Germany had transferred €2 trillion (£1.76 trillion) to former East Germany, sparing it the need to make cuts to its research system; in contrast, attempts by Polish universities to hire a new generation of researchers locally were often hampered by the economic turmoil typical of the post-communist era as former Eastern Bloc countries struggled to adapt to a market economy.

Let’s see the big hitters: citation impact v GDP per capita on either side of the Iron Curtain

Renata Siemieńska, a professor at the University of Warsaw’s Robert Zajonc Institute for Social Studies, recalls that her institution hired “a number of young, bright people” who were nonetheless forced to take second jobs to make ends meet, sometimes at the new private higher education institutions that sprung up as the system was liberalised post communism. This prevented them from properly developing their research skills, she says: one took on 17 jobs; others simply emigrated: “It was really extreme.”

The members of this “lost generation” of “scientific capital that was not developed” are now in their fifties and sixties, and, having largely failed to gain permanent positions, are no longer researching, Siemieńska adds.

The problems were exacerbated by the fact that research was not at the top of post-communist Poland’s priority list, which focused instead on teaching. The transition from communism would have been “impossible” without “enough people who were well educated”, Duszczyk says. The country needed to rapidly teach people how to function both in a democracy and a market economy.

Jerzy Duszyński, president of the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN), concurs with this analysis and points out that Poland has made huge gains in its higher education enrolment rate. In 1989, just 8 per cent of the country’s young people went to university; that figure now stands at 43 per cent.

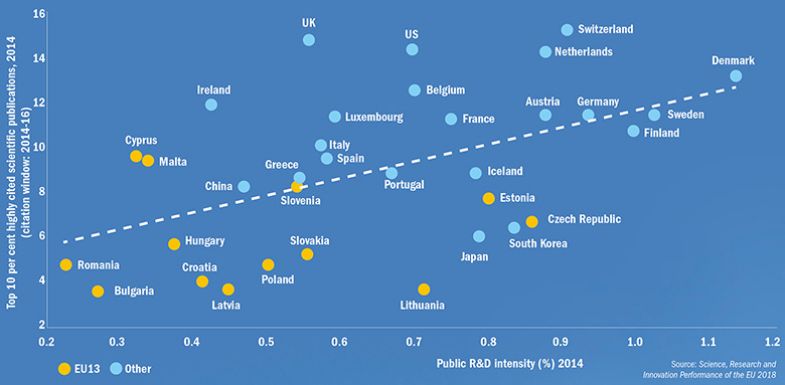

The EU’s underachievers: EU13 punch below their public R&D weight

According to Siemieńska, it is misguided to assume that poorer countries can close a research gap with the rich world in the same way as they can close an economic gap. Companies in wealthy countries often outsource production to poorer countries to benefit from lower wages; from this, the less-developed economy hopes to gain more investment, more jobs and more know-how to boost its growth. But this catch-up method cannot easily be applied to research – particularly if, as in the natural sciences, the capital costs of lab equipment are high.

“You cannot just say everything is cheaper in Poland. It’s not cheaper because you have to use exactly the same facilities that people have in Michigan, Berlin or London,” Siemieńska points out.

Low wages for manufacturing workers in Poland might induce Volkswagen to set up a factory there, but low wages for Polish biochemists might spur them to emigrate to the US. Academic wages in post-communist countries are simply “not competitive”, says Pasternack, which causes a brain drain. “That’s just academic capitalism,” he notes.

The accumulation of these disadvantages means that in Poland’s higher education and science system, “performance and innovation outcomes remain sub-optimal”, a panel of foreign observers warned in a report , Poland’s Higher Education and Science System, for the European Commission last year. Even controlling for how much the country spends on research and development, Poland is “clearly underperforming in terms of scientific quality”, it says.

The same is true for all post-communist EU member states except Slovenia, according to a commission report released earlier this year, Science, Research and Innovation Performance of the EU 2018, which finds that post-communist countries produce fewer highly cited papers (either in the top 10 or 1 per cent) than would be expected given their level of investment in public research and development. “The resources put into public research in countries like Estonia, the Czech Republic [and] Lithuania…do not appear to lead to sufficiently high-quality results,” it says.

The 2017 inspection of Poland’s system offered up a familiar recipe of recommendations: the country, it said, should develop a handful of its universities into “internationally competitive research-intensive” or “flagship” institutions. It should also introduce tuition fees; empower managers and weaken the role of academics; create more links with business and wider society; and internationalise through the circulation of students and staff to and from Poland.

The report also took particular aim at Poland’s network of 114 public research institutes – which employ more than 12,000 researchers – as well as the Polish Academy of Sciences (PAN), a separate network of 70 organisations, employing 8,000 academics. The best-performing institutes should be merged into research-intensive universities, the report recommended, which would “raise the international visibility of Polish science and improve the performance of its universities in the global rankings”.

As in Germany, Polish research is still split between public institutes and universities. This is a far cry from the English-speaking world, where universities dominate – and it still irritates Janusz Grzelak, a member of the democratic opposition during the dying days of the communist regime, who became deputy higher education minister when it fell. Grzelak, now in his seventies, says he wishes that he had been able to do more to bring universities and research institutes together. This is something that Estonia did – with the result that its top institution, the University of Tartu, is now ranked significantly higher than Warsaw. It is in the 301-350 band in THE ’s World University Rankings, and tops THE ’s New Europe Ranking, which covers universities from the EU13 (Warsaw is sixth).

“We were naive,” Grzelak says. “[But] it wasn’t possible at that time. The academy was very strong and still is very strong. I think it is still wasting money, in terms of human resources, laboratory equipment…separate administration…you have to pay double.”

Warsaw’s Duszczyk agrees that folding Poland’s institutes into its leading universities would “improve our place in the [world] rankings”. And while he does not “fetishise” rankings, he perceives that “if you don’t have any ERC grants or a position in the rankings”, you are “outside the club” of research-intensive universities. Hence, he admits, rankings are always “at the back of my mind”.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the academy’s Duszyński disagrees. His solution is for all PAN’s institutes to be recognised as a single graduate-level university, and for the conglomerate to be awarded Zl100 million (£20.7 million) annually for seven years to help it attract foreign students and researchers.

“We need such a university not only in terms of image and prestige; it will also serve to attract further scholars and students from [around] the world,” he says. This should tackle academic “inbreeding” – the lack of national and international research mobility – which he sees as the biggest problem in the Polish system. “The internationalisation rate at the leading universities is at most a few per cent for students, and significantly less than that for faculty,” he says.

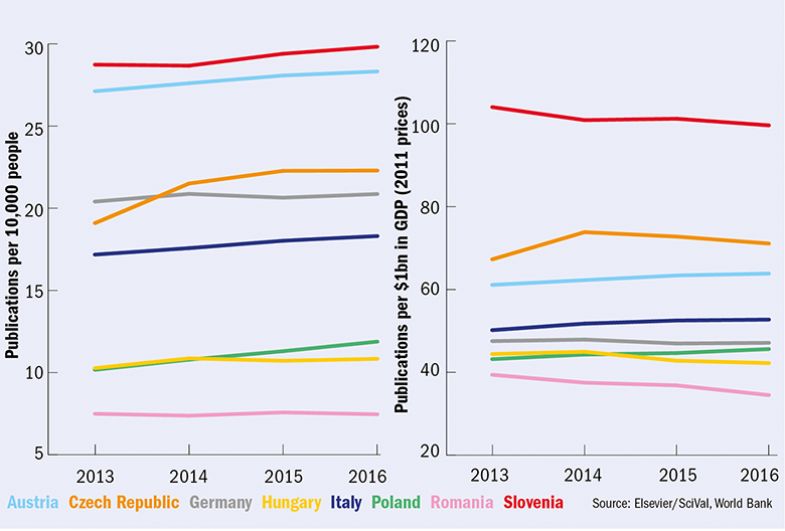

Investment returns: research output

National academies are a common legacy of the Soviet system, and they still exist in most former communist countries, according to Pasternack. Fittingly, the headquarters of the Polish version is housed in the Palace of Culture and Science, a towering Soviet building in central Warsaw that was originally dedicated to Stalin.

But the idea that these academies are holding back post-communist countries by scattering top minds and money across too many institutions is overly simplistic, according to Pasternack. The Max Planck Society is the biggest winner of EU Horizon 2020 grants, for instance, and France’s National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) is also highly regarded.

In Poland, another hindrance is a situation that Grzelak says he regrets not having managed to change: the system whereby academics must in effect complete a second PhD, called a “habilitation”, before they can be considered for a professorship. The average age at which full professors are recruited in Poland is 50, according to the European Commission report, which is “significantly higher than in most competitive HE systems”. A similar system exists in Germany, however.

The report also highlights the fact that Poland’s university system “remains fragmented into a few big and many very small institutions”. Of the country’s 415 institutions – one of the highest per-capita densities in the EU – nearly 300 are small, private and enrol only a few hundred students a year, it found. Duszyński agrees that many of these institutions are “small and weak”, but, he adds, they are points of pride for Polish regions and cities, and are staunchly defended by local politicians. This means, according to Siemieńska, that whatever reforms the government will push through – and this is still not clear – funding will not be as concentrated as the research-intensive universities hope.

However, there could yet be a cull of institutions that even local politicians cannot fight as a consequence of demographic changes that are occurring across the countries of eastern Europe. Student numbers peaked in the mid-2000s and have since dropped by roughly a quarter. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of Polish institutions fell by nearly 50, according to the commission, and Poland’s Ministry of Science and Higher Education expects the number of private institutions to shrink by up to half over the next five years, it adds.

EU13 countries have so far had limited success in attracting overseas students to make up the declining enrolments. Just 3.4 per cent of students in Poland come from abroad, according to the most recent Unesco data. Estonia (5.2 per cent), Bulgaria (4.6 per cent) and Romania (4.8 per cent) have done a little better, while Hungary (8.9 per cent) and the Czech Republic (10.6 per cent) are approaching levels normal in western Europe.

Authoritarian politics have also cast a shadow over the prospects for research in eastern Europe. In February, the Polish government passed a legal amendment that criminalises the attribution of responsibility for the Holocaust to Poland or Poles; there is an exemption for academics, but historians fear that this is unclear and could mean that their work is subjected to censorship.

Meanwhile, in Romania last year, academic critics of the government accused it of seizing control of research councils in order to reward cronies after it removed overseas evaluators.

And in Hungary, the future of the Central European University remains uncertain after it was placed in legal limbo last year by the introduction of legislative changes that critics say are aimed at silencing liberal opposition.

Warsaw’s Duszczyk is confident that Poland’s Holocaust law will not interfere with research. “I trust [in a] strong, free Polish society” to prevent political influence over universities, he says. “That’s why I don’t think someone from the government will start a war with the universities.”

As for his institution, it has grand plans for its future, aiming to double its number of ERC grants over the next five years. And, in March, it pledged to deepen its relationship with Charles University in Prague, Sorbonne University in Paris and Heidelberg University as part of a “European University Alliance”.

But Grzelak holds a darker view of the impact of Polish politics on universities.

“I feel threatened by what’s going on in Poland now,” he says. “Very threatened.”

后记

Print headline: Eastern blocks