In March this year, scholars across the world were alerted to the fact that something was seriously wrong in Hungary.

The country’s top-ranked institution, the Central European University, sounded the alarm that new government legislation would, in effect, force it to shut down. The former communist nation’s right-wing government, led by prime minister Viktor Orbán, was proposing to require foreign universities such as the CEU to maintain a campus in their home countries and to ban them from awarding degrees in the absence of an agreement between their home government and Hungary’s. The CEU, founded and funded by Hungarian-born and US-based billionaire philanthropist George Soros, is co-accredited in Hungary and New York state but operates only in Budapest.

A petition quickly garnered 50,000 signatures from around the world, and an open letter was signed by 500 senior academics and 20 Nobel laureates. Nevertheless, the legislation was passed by a huge majority by the Hungarian parliament in early April.

According to critics, the CEU – set up in 1991 to fortify liberal democratic institutions following the fall of communism two years earlier – is the latest target of an increasingly authoritarian Hungarian government intent on neutering civil society groups: particularly those funded by Soros. Some Hungarian academics have even become afraid to speak out publicly, claiming that the situation under what Orbán has termed “illiberal democracy” is worse than it was in the latter years of the pre-1989 communist regime.

Critics of Orbán – who was a feted liberal reformer in the dying days of the communist era – agree that the humanities and social sciences have suffered particularly since he came to power in 2010, and some attribute a political motivation to that.

“Humanities are very important for teaching critical citizens,” notes Zoltán Fleck, head of the Centre for Theory of Law and Society at Budapest’s Eötvös Loránd University. “Teaching history, literature, humanities…is quite dangerous for authoritarian regimes.”

But there is also a more pragmatic explanation. Many in Hungarian academia believe that, for all Orbán’s own academic background – he studied law at Eötvös Loránd before obtaining a Soros-funded scholarship to study English liberal political philosophy at the University of Oxford – he has lost faith in universities’ economic importance.

Liviu Matei, a professor of higher education and the CEU’s provost, notes that there has been a “change of attitude” towards Hungarian higher education since Orbán’s Fidesz party came to power. “The dominant discourse in Europe since the late 1990s was that higher education is important…because it creates knowledge, through either research or skills capacity,” he says. But in Hungary, higher education is now seen by the government as a “luxury”, with the country needing fewer students, not more.

According to Norbert Sabic, a strategic planning assistant at the CEU and a higher education researcher, Orbán has turned his back on the “knowledge economy” orthodoxy – of which mass higher education is a key part – after witnessing Hungary’s failure to catch up with Western European economies following the fall of communism. Instead, the prime minister thinks the country’s brightest future lies in becoming a relatively cheap manufacturing hub for German companies, Sabic says.

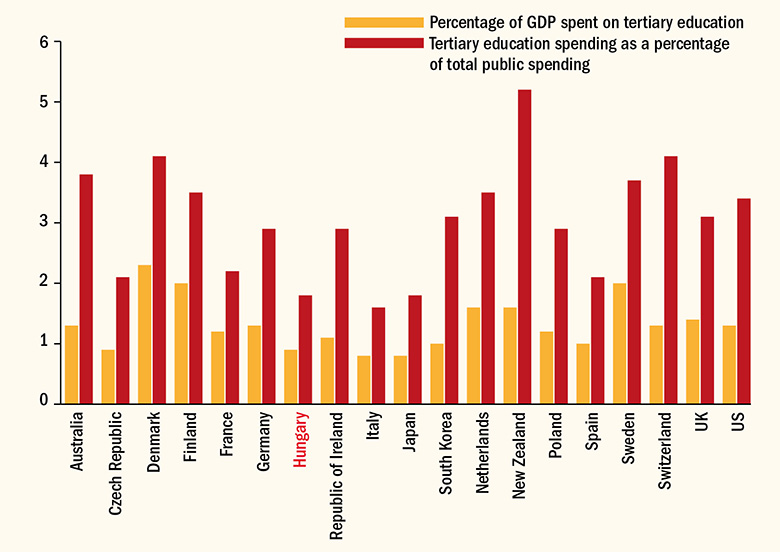

Tertiary education spending, 2013

Source: OECD

The statistics bear out this analysis. While many countries tightened their belts in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Hungary cut back on tertiary education more than most. Between 2010 and 2015, public funding for higher education as a proportion of GDP dropped by 18 per cent: more than any other country in Eastern or Central Europe except Greece and Lithuania, according to European University Association figures. And the most recent data from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development show that public spending on tertiary education accounted for just 0.9 per cent of Hungary’s GDP in 2013, and 1.8 per cent of all public spending. These are some of the lowest rates among OECD members.

Meanwhile, in 2011, the government cut the compulsory secondary school leaving age from 18 to 16. Since then, the number of students receiving the matriculation certificate needed to enter university has fallen by nearly a quarter, according to Eva Balogh, a former lecturer of Eastern European history at Yale University, who writes about Hungarian current affairs.

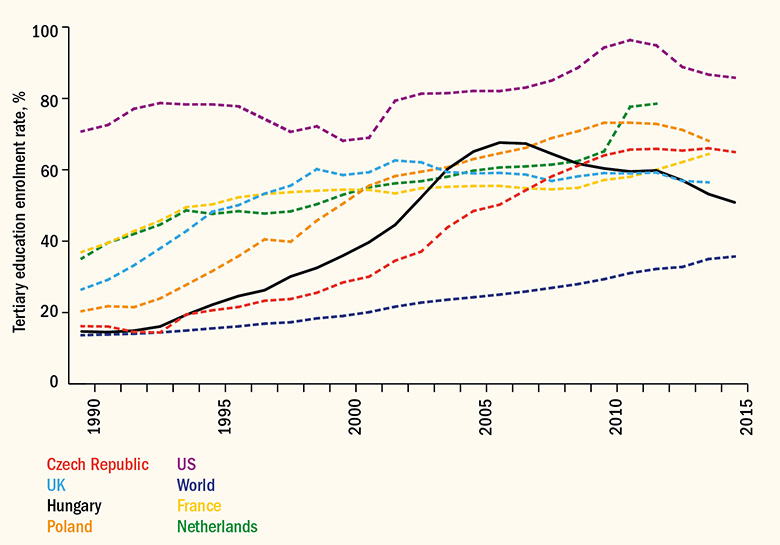

Tertiary education enrolment rates since the fall of communism

Source: World Bank

Student numbers have dropped accordingly. Between 2010 and 2015, they fell by 18 per cent, according to the EUA data (only Estonia saw a bigger tumble). Many observers say this is explained by an ageing population, and, indeed, other Southern and Eastern European countries have also seen sizeable recent falls. But, as well as falls in absolute numbers, tertiary enrolment rates have tumbled in Hungary, too, according to World Bank data. A decade ago, Hungary had an enrolment rate of more than two-thirds: higher than that of the UK, France or the Netherlands. But, since then, the EU average has steadily ticked up, while Hungary’s has plummeted to just over 50 per cent.

One of the first signs of the political tide turning against higher education came in 2012, explains Kata Orosz, an associate research fellow in higher education at the CEU. Orbán railed in a speech against students for supposedly wasting their time in Budapest’s edgy underground “ruin” bars, the trendy drinking spots that have popped up in the city’s derelict spaces. Hungary’s education system, he complained, had produced people with only useless knowledge, and had failed to turn out enough manual labourers, such as truck drivers and product assemblers. “Not everyone will become a researcher or a laboratory worker, but I respect people who do manual labour and I am happy to help them find a job,” he said.

Legal scholars complain that there are now little more than 100 publicly funded places to study law across the whole of Hungary, although the government says that the figure was 259 in 2017. Students can pay fees to get around this, but these are very expensive relative to average wages, says Péter Hack, head of the department of criminal procedure and correction at Eötvös Loránd and, until 2002, an MP for the once powerful but now defunct liberal party, the Alliance of Free Democrats. “In the long term, just rich, upper-middle-class people will be able to have a law degree,” he believes.

Meanwhile, in 2015, it took street protests to stop the government phasing out certain social science subjects, including international relations.

According to Orosz, another mark of the government’s new utilitarian attitude is that it sends students letters explaining how much the state has spent on their education. Students are also required to work in Hungary for as long as the length of their studies at some point during the 20 years after they graduate.

Government spokesman Zoltán Kovács rejects the idea that Hungary has abandoned the “knowledge economy”. But he does say that the country is adopting a system based on “quality”, not student quotas: “Many in this country have sent their kids to university…even if [the subject they studied] was not a marketable area of knowledge. And, in that, we definitely need a change,” he says.

Those who want to go to university need an “immediate” way to capitalise on what they have learned in the labour market, Kovács adds, mentioning telecommunications, computer programming and car manufacturing as preferred areas. Under Fidesz’s new system, the number of students in each discipline is determined “according to the real market need”.

Kovács himself studied history at the CEU. But when asked how is it possible to assess the market need for history graduates, he does not answer directly, observing only that, “The market need is very clear because it’s not dictated by the government: it’s dictated by life.”

So what about the accusation that Fidesz is pursuing an authoritarian agenda against universities?

Kovács bristles at the suggestion: “We are going to have a difficult interview here if I always have to answer the politically or emotionally charged statements of the opposition,” he says.

Orbán’s critics point to the government’s recent establishment of a new generation of higher education institutions, claiming they are designed to keep academics and students loyal, and to steer public discourse in officially palatable directions. Chief among these is the National University of Public Service, opened in 2012, whose vast new campus – complete with horse-riding facilities – is taking shape on a site in the south-east of Budapest.

Kovács says the institution, which brings together the training of police, military and civil servants, is Hungary’s attempt to replicate the grandes écoles of France. “This is a must [for] the state,” he says. “Our proposal is that those who want to engage with public service at one level or another will have to be engaged with this university.” But Eötvös Loránd’s Fleck fears it could soon swallow all of the remaining publicly funded places in law, while Hack claims that the new institutions “recruit professors who are loyal. There are some who are critical, [but I only] know one: not more”.

Another source of controversy is the historical research institute called Veritas, opened by the government in 2013, which some argue is trying to downplay the gravity of Hungary’s past antisemitism. The year after it was set up, for instance, Jewish groups called for the resignation of its director, Sándor Szakály, after he reportedly described the deportation of Jews from Hungary during the Holocaust as “police action against aliens”.

A spokesman for the institute responds that “police action” is a poor translation, which was “used to paint Szakály in the worst possible light”. What Szakály actually said, according to the spokesman, was that the first deportation of Jews from Hungary was an “immigration procedure”, removing those without Hungarian citizenship. He was only referring to one specific incident in 1941, the spokesman said, not the entire Holocaust.

Critics also perceive creeping political control of universities through new chancellor positions, created in 2014. These figures, appointed by the prime minister, oversee university spending and have the final say over recruitment, salaries and promotions, according to the EUA. This explains why Hungary dropped from sixth position to 28th (one from bottom) on the association’s financial autonomy scorecard between 2011 and 2017.

According to Sabic, it is “not always” the case that the new chancellors are political stooges, and he doesn’t believe that they take orders directly from the government. But they do “want to help the government agenda”. For example, when the CEU crisis began, a number of academics from the University of Debrecen in Eastern Hungary wrote a public letter of protest. But “the chancellor [there] stepped up and said that they were not saying this in the name of the university because they did not have the privilege to do so,” Sabic says. Debrecen’s chancellor did not respond to a request for comment.

Another check on institutional autonomy, introduced at around the same time, are “consistoriums”, he adds. These are rather like Anglo Saxon-style boards of trustees, with responsibility for the “long-term decision making” of the university. Three out of five members are appointed by the ministry, although a government spokesperson insisted that candidates are put forward by the university itself, student unions and other organisations with ties to the institution.

According to government spokesman Kovács, the chancellors were brought in to control universities’ ballooning debts. Universities “were not very careful about spending public money”, and the chancellors have since “consolidated” their institutions’ debts. He insists their appointment has “nothing to do with academic freedom”, but when asked whether they give the government power over universities, he responds: “All over the world, the one who gives the money also gives the rules.”

That observation also applies to research funding. According to Fleck, money remains available for research in his field, law. But the minister of justice plays a role in setting the research agenda, meaning that recipients have to “behave well”. The minister’s most recent focus is the family: a conservative theme that has become a “cornerstone of the government’s ideology”, Fleck says.

Another academic and grant evaluator, who prefers to remain anonymous, likens the current situation to the communist funding system, in which applicants had to add a “red tail” to their proposals, voicing “something pro-system”. As an example, he says some proposals he has read for research into foreign cultures justify themselves on the basis that the Hungarian government wants better trade links with those countries. Still, one might ask how different this is from UK funders’ demand that research generates social or economic impact, and the anonymous academic acknowledges that this is “a very slippery area”.

Yet the fact that he seemed visibly nervous as he spoke to Times Higher Education in a Budapest cafe, constantly glancing around to see who might be watching, is emblematic of the fear some Hungarian academics have about speaking out against what is happening. The academic says morale among many faculty is very low, and he confides that he is applying for jobs abroad: “I don’t want my kids to be raised in these circumstances. And I think all of the younger generation are considering [doing the same].”

Hack says the current situation is worse than it was under the last decade of the communist regime, when, as a young academic, he was able to criticise leading police figures to their faces on television. He doubts whether he would get away with that today. A historian friend of his “doesn’t have any hope of getting any money from the government for his research” and was recently forced off several academic boards after criticising “a certain decision” by the government. For publicly critical academics in Hungary, there is now “a clear and present danger that you can suffer some kind of repercussion…both individually and institutionally”.

On the other hand, academics still have “considerable” freedom to decide on curricula, says Fleck. At Eötvös Loránd, for instance, it looks like a new gender studies course will go ahead, despite criticism from a politician at Hungary’s Ministry of Human Capacities. And the Washington-based thinktank Freedom House says that “the [Hungarian] state generally does not restrict academic freedom”, although “selective support by the government of certain academic institutions…threatens academic autonomy”.

In light of what has happened to higher education in Hungary since 2010, the move against the CEU earlier this year seems less surprising. But why has it happened now? One suggestion is that Orbán felt emboldened by the election of Donald Trump; some see the two as ideological bedfellows, and Republicans regularly take up the attack against Soros, a major donor to the Democrats.

When the CEU crisis first broke, the Hungarian government’s line was that its new law was simply a regulatory response to an investigation of foreign campuses. But addressing a domestic audience on Hungarian radio, Orbán said in April that the “milk had curdled” with regard to the CEU because of the attitude of the “Soros empire” towards migrants and refugees. The CEU offers university top-up courses for refugees and asylum seekers legally admitted to Hungary, and when, in 2015, refugees found themselves stranded at railway stations in the capital, the university helped to coordinate donations and to provide wi-fi, phone charging and translators.

When THE put it to Kovács that the CEU has been deliberately targeted for its politics, he said that from the late 1990s, “it became evident that CEU was training personnel that were not only dealing with professional issues…but there are areas – political sciences, gender, other studies – where there is an ideological element of education”.

He insists that ministers “don’t care about that”, and that “it can continue”. But he goes on: “There are times…when these ideological differences can manifest [themselves] in political form. And that’s what we saw in the case of migration,” he says. Orbán has repeatedly accused Soros of trying to flood Europe with migrants, whom he has described as “a poison”, while the prime minister has been widely criticised internationally for holding refugees in detention camps while their cases are investigated.

“There are countries in Central Europe and the European Union that have rules and laws” that conflict with what is believed by “CEU-trained or Soros-trained individuals”, Kovács says. “That conflict should be sorted out in some way.”

But is the migration issue the true cause of the Hungarian government’s anger, or only a convenient excuse? For his part, Michael Ignatieff, the CEU’s president, believes the issue is only “secondary”. “I think Mr Orbán is coming after this university because it was founded by Mr Soros,” he says.

Some in Hungary believe the government came under pressure from pro-Russia regimes across the region, who resented the presence of so many CEU graduates among the staff of other Soros-funded organisations in their midst, campaigning for transparency. Kovács says the Hungarian government has found “evidence” of this CEU influence “because we’ve taken a look at the CVs” of those who work in Soros-funded NGOs. But he repeats that the new law regarding foreign universities has nothing to do with restricting academic freedom.

As things stand, the CEU will no longer be able to take new students from the beginning of 2018. There have been talks between the Hungarian government and the state of New York, and reports in the Hungarian press that this might soon lead to an agreement that would allow the CEU to stay, but as THE went to press, nothing concrete had been announced. The CEU feels like a “university under siege”, says Ignatieff. “We’re getting to a point where we’ve got to have a deal.”

There is some evidence that the government’s popularity has taken a hit since the CEU controversy, so perhaps a solution may yet be found. But many of those willing to speak to THE are pessimistic about the chances.

If the CEU does have to leave Hungary, it will be seen internationally as quite a defeat for liberalism in Europe – and quite a landmark in the history of Hungary’s “illiberal democracy”.

后记

Print headline: Voices from Hungary as sanctions tighten