Source: Alamy

North America has more professors and more differentiated positions. The status distance between professors and non-professors is not so big

When Eric Labelle applied for a tenure track assistant professorship at the Technical University of Munich, the position did not seem anything out of the ordinary. Born and raised in Canada, Labelle was accustomed to the structure of academic careers in North America, where tenure track, although under pressure, is the norm.

During the interview process, he was surprised to learn that junior jobs that lead directly to a permanent position are rare in Germany and across Europe as a whole. Now in post – Labelle won the job and began work at TUM in September – he finds it “a bit strange that it is not common here…What is the alternative?” The alternative, of course, is the bitter reality that thousands of early career researchers across Europe wake up to every day: attempting to build an academic career via a series of fixed-term posts, usually at different institutions, without knowing whether the opportunity to secure a permanent contract will ever arise.

It is the dream of many young academics to be in the position of Labelle. His tenure track assistant professorship in forest operations offers him a six-year contract with the promise of a permanent professorial post if he meets the required standards. It is part of a scheme launched in 2012 by TUM, in conjunction with the Max Planck Society, Germany’s research powerhouse, which aims to create 100 tenure track professorships by 2020. Last year, Wolfgang Herrmann, TUM’s president, told Times Higher Education that the university had introduced the scheme to attract the brightest junior scholars worldwide. Without offering tenure track, he reasoned, German institutions were less attractive than those in the US.

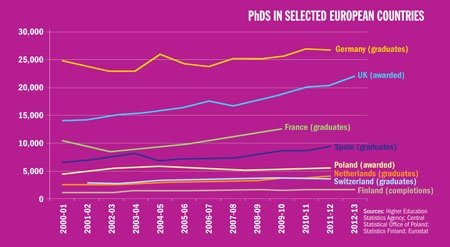

TUM is one of a growing number of universities in Germany and in Europe more widely that are beginning to offer tenure track positions to junior academics. The move is part of a broader set of changes to academic career structures on the Continent, according to Tatiana Fumasoli, a postdoctoral research fellow at the ARENA Centre for European Studies at the University of Oslo, and co-editor of Academic Work and Careers in Europe: Trends, Challenges, Perspectives (2014). Among other things, she says, governments and institutions are having to respond to international competition for researchers and a growing recognition that scientific excellence can spark socio-economic development in a country. And as the number of PhD students across Europe grows, ramping up competition for academic posts, some countries are exploring new ways to open up academia to those who face poor odds of securing a professorship.

As part of a European Science Foundation-funded project, Fumasoli and her colleagues examined academic careers in eight countries: Germany, Switzerland, Romania, Croatia, Finland, the Republic of Ireland, Poland and Austria. Each has a different tradition, and local practices remain important, particularly in the more junior stages of academic careers.

In Germany, in some parts of Switzerland and in Poland, universities generally have vertical structures organised around dominant professors. A full professor or chair “is very powerful, and around her or him there is a group of other professors, maybe junior professors and assistants, PhDs and postdocs”, says Fumasoli. In the UK, Ireland and North America, of course, universities tend to be organised in a departmental structure, which has a more horizontal organisation. “There is no big boss and chair holder, but there are many more professors and more differentiated positions. The status distance between professors and non-professors is not so big,” she says.

The age at which academic independence can be achieved also varies considerably between countries. Although competition for permanent positions is intense, academics in the UK and Ireland can potentially secure a permanent contract relatively early in a career compared with their counterparts elsewhere in Europe, in positions such as lecturer or reader.

Academic independence can also be won relatively early in France, where post-PhD junior academics can apply for the position of maître de conferences, generally considered a permanent civil service position roughly equivalent to assistant or associate professor. France’s “unique model for academic careers” provides permanent positions for academics between the age of 28 and 38 and attracts “very young and motivated researchers”, says a report published last year, Tenure and Tenure Track at LERU Universities: Models for Attractive Research Careers in Europe. However, the report continues, “as with other tenure models it entails a risk of binding staff members for a lifetime at a relatively young age, with possible implications for efficiency and competitiveness”.

Before progressing to a professorial post, many academics in France require an habilitation – a postdoctoral qualification or equivalent achievements that confer eligibility for a professorship. This route is also seen as necessary for independent research and teaching at professorial level in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Denmark and Poland. In all these countries, positions for academics without an habilitation are generally fixed-term ones.

Despite differing traditions, Fumasoli and her colleagues found that the stages of an academic career are becoming more clearly defined across the eight countries they examined. Although the terminology may vary by country, early career researchers typically start out as a PhD student then move into a postdoctoral or junior researcher position, followed by a junior professorship and finally a full professorship. Career structures and the processes for recruitment and promotion are increasingly formalised, organised and standardised across the eight countries, too. One example is the trend for PhD students to enrol in doctoral schools; another is the tendency to put out international calls for recruitment to research posts.

For Fumasoli, these are all positive signs. “The fact that there is more transparency, calls are international and the evaluation [of candidates] is standardised is to the advantage of junior [academics], especially in countries where an academic oligarchy made up of very senior full professors [is in] control,” she says.

In Germany, the tradition of habilitation appears to be waning. According to data from the 2013 National Report on Junior Scholars, registrations of the qualification in 2010 were 18 per cent below the level of 2000. At the same time, new academic training routes for postdoctoral researchers are opening up. These include junior professorships, which allow early independence in research and teaching, although such positions tend to be concentrated in particular disciplines. “Junior professorships can begin at the age of , which is seen as a ‘decisive change in academic careers’ compared to formerly, when there were ‘waiting loops’ before you could hold a chair at the age of 40-50 years,” says Academic Work and Careers in Europe.

With the ratio of doctorates to vacant professorships running at an average of 20:1 in Germany, the German Rectors’ Conference (HRK) has been encouraging universities to develop additional career paths to help early career researchers find a place in academia. It addressed the topic last year in a paper titled “Guidelines for the advancement of early career researchers in the post-doctoral phase and for the development of academic career paths in addition to that of professorship”.

“We need more professorships in Germany, but there is no money at the moment for establishing more of these positions,” explains Henning Rockmann, head of the legal department of the HRK. Universities are being encouraged to look beyond “this special position of professor” and to create new posts in teaching or research, he says.

Often a permanent post comes only at about 40. Between your PhD and your professorship you spend 10 years completely unsure what is going on

In Switzerland, meanwhile, young researchers are unhappy about their lot. PhD holders who want to stay in the academy have to complete several postdoctoral positions on short-term contracts without knowing whether they will secure a permanent position. “Often it is decided only at the age of about 40, so between your PhD and your professorship you spend 10 years completely unsure what is going on,” says Corina Wirth, a scientific adviser to the Swiss Federal Department of Economic Affairs, Education and Research.

As professorships are rare, researchers must be open to the idea of going abroad to secure the all-important title, she says.

Of those who complete a doctorate in Switzerland, 54 per cent leave academia within a year of graduating, explains Wirth. And many are deterred from even embarking on a PhD because of the plentiful opportunities outside the academy. “The economy is going quite well and there are a lot of really interesting positions outside academia,” she says, pointing to the country’s many research-intensive companies such as Nestlé, Novartis and Roche, which have an abundance of positions for scientists.

For those who tenaciously pursue an academic career, the prospects are bleak for those fail to secure a permanent post. “At the age of 40…it is very difficult to get a position in industry,” Wirth says.

In May last year, the Swiss Federal Council published a report (Measures to Encourage Young Academics in Switzerland) setting out these issues, and the country’s parliament is now putting pressure on universities to change the system by questioning whether openings should be advertised as “tenure track” positions rather than as postdoctoral positions.

But there is a limit to the Swiss government’s powers: most institutions are regulated by the country’s member states, known as cantons. The government has control only of the two federal institutes – ETH Zürich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich and the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne – which have already introduced tenure track posts. The cantonal universities have little motivation to change their ways because they are already successful in attracting international scholars.

Finland also faces a bottleneck for professorial posts. Tapani Kaakkuriniemi, the president of the Finnish Union of University Researchers and Teachers, says that Finns are often reluctant to leave Finland to pursue opportunities overseas, which exacerbates the problem.

As in many other countries in Europe, the path that leads to a professorship consists of a series of temporary posts.

For Kaakkuriniemi, it is the oversupply of doctorate holders that is “key” to Finland’s problems in the academic career structure. “Every year something like 1,700 new doctors are successful defending their dissertation. Universities at present can only hire less than 30 per cent,” he says. “There are not enough professor posts vacant.”

Finnish universities began offering tenure track positions at associate or assistant professor level in 2010. At least 10 of Finland’s 14 institutions now offer some kind of tenure track post, but the number of positions available remains small and institutions are still refining how they work in practice, says Kaakkuriniemi, who does not see tenure track as a cure-all. “Some universities have already noticed that they only have the ability to offer these posts to people who are coming along on the first and second level [post PhD]…Tenure track favours people who are in their late twenties or early thirties,” he says, adding that it is not clear what universities can offer people in their forties and fifties who have a great deal of experience.

Nearby in Sweden, where fixed-term contracts are also common, universities were given greater autonomy in 2011 to decide how career paths are structured. As a result, institutions tend to have different career structures, and only the posts of senior lecturer and full professor – general permanent positions – are the same across the sector, says Karin Åmossa, senior researcher at the Swedish Association of University Teachers (SULF).

About 10 per cent of Swedish academics are working in so-called career development posts, of which just 1 per cent hold associate lecturer positions, which potentially lead to tenure. The remaining 9 per cent, according to the SULF, hold postdoctoral research or research fellowships, which typically last three and four years respectively and come with no promise of further work.

“In reality we can have people for 10 or 20 years on different short-term contracts,” Åmossa says. Universities defend this by arguing that they do not know how their income will change in the years ahead.

Åmossa identifies a gap between rhetoric and reality over the issue of tenure track positions. “In theory more and more universities are trying to build tenure track,” she says. “Some, for example Lund University and Stockholm University, have created tenure track on paper…the problem from our view is that they do not put any people into it,” she claims.

But technical institutions, such as the KTH Royal Institute of Technology, have a higher share of academics in tenure track positions because they face stiff competition from industry. “You cannot make people stay if you don’t offer them a good position,” Åmossa points out.

In Poland, an expected injection of European Union structural funding offers hope to early career researchers. After a programme of investment in research and higher education infrastructure from EU structural funding, EU regional development funding and the Polish government, attention is now turning to talent.

Michal Pietras, director of the programme division of the Foundation for Polish Science, says the funding presents “a real opportunity to expect programmes co-funded from the EU structural funds for research programmes and research groups” that will benefit early career researchers.

Opportunities for junior researchers to gain faculty positions at universities in Poland are few and far between at the moment, he says, although various grant funding streams for postdoctoral researchers exist. According to Academic Work and Careers in Europe, however, Poland has a clear tenure track route and the problem of postdoctoral academic careers “is not so much obtaining a permanent position as the low salary level these positions offer”.

So how does this compare with trends in the UK? Vitae, the research career development organisation, has done much to improve academic research careers, says Sally Hunt, general secretary of the University and College Union. Vitae manages and implements the Concordat to Support the Career Development of Researchers, for example, which is an agreement between funders and universities that sets out clear standards for employing researchers.

But Hunt says that academic research in the UK remains a “highly precarious career” compared with other highly skilled professions. “The predominance of fixed-term posts can make a UK university research career an unattractive one and hard to pursue in the long term,” she says, adding that there has been a marked lack of progress on reducing their use. According to figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency, the number of fixed-term academic posts increased by 8 per cent between 2008 and 2013.

While there are some positive signs – a number of UK universities have introduced tenure-track style schemes (see box below left) – some higher education institutions appear to be trying to “roll back earlier collective gains” made to the redundancy regulations surrounding fixed-term positions, Hunt claims. “This can only make UK universities a less attractive place for researchers,” she warns.

Career structures in Europe

Three basic models for progression up to professorship level:

- Probation on the job

UK - Two-tier promotion and habilitation

Central Europe - Centralistic with state approbation

France

Source: Tenure and Tenure Track at LERU Universities: Models for Attractive Research Careers in Europe (2014)

Secure steps: UK institutions pave the career pathway

“Entering an academic career now is much more challenging than it was 25 years ago for many reasons, partly because academics have to do many different things in the early part of their career,” says John Fisher, deputy vice-chancellor of the University of Leeds.

Leeds is the latest of several UK institutions to unveil a tenure-track style scheme for junior academics. Over three years, its 250 Great Minds initiative, worth £100 million, will recruit 250 early career researchers on to a career development programme. This will lead to a permanent associate professor post, provided that they fulfil a set of requirements.

In 2001-02, the university ran a similar scheme of 100 early career fellowships, based on the now discontinued Roberts funding, which was supported by the Higher Education Funding Council for England and research councils, and it now hopes to recreate some of the benefits.

“When we looked at the successful development of those people 10 years on, it [was clear that it was] a really good thing to do,” says Fisher.

During the first three years of the five-year Great Minds programme, the beneficiaries will focus on developing an independent research profile. In the final two years they will take part in training, including a postgraduate certificate in higher education.

Fisher believes that other universities will develop similar schemes in the years ahead. “It is the time in the seven-year research excellence framework cycle to appoint new staff because they can develop in the period and then be submitted to the next REF,” he says.

“We are investing an awful lot in this country on PhDs and doctoral training centres, we are bringing people through, in my mind this [next part] was an area of the career path that needed a strategic boost…We have got to make a career path in academia attractive to people,” he says.

The University of Birmingham, meanwhile, has recruited three cohorts of early career researchers into its Birmingham Fellows initiative since 2011. This gives junior academics with a PhD a five-year fellowship followed by a guaranteed permanent position if they meet certain criteria.

And the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences at the University of Liverpool has used money from the Wellcome Trust to establish a series of tenure-track fellowships that are designed to lessen the teaching and administrative burden on early career academics, allowing them to focus on research.

Holly Else