Just this August, a story emerged of a medical centre in Arizona that was accused of illegally selling body parts against the wishes of donors. One of the plaintiffs suing the centre believed that his mother’s body would be used to study Alzheimer’s disease, but he later found out it was sold to the US military for use in testing the effects of explosives.

This is just the latest episode in the long and disturbing history of the unethical use of human remains by medical institutions. When I read about it, I was reminded of the practice of the Irish surgeon John Timothy Kirby (1781-1853), who used exhumed bodies when lecturing on gunshot wounds to his students. As The Lancet reported in 1824, “The subjects being placed with military precision along the wall, the Lecturer entered with his pistol in his hand, and levelling the mortiferous weapon at the enemy, magnanimously discharged several rounds, each followed by repeated bursts of applause.”

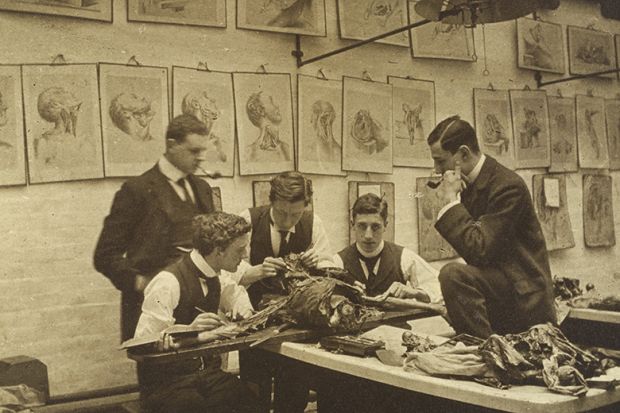

Kirby twice served as president of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland (RCSI) and so was a central figure during a period widely considered the “golden age” of medical education in Dublin. But this golden age had a distinctly dark side: leading surgeons regularly mistreated corpses and engaged in “bodysnatching” as a routine means of providing their students with “subjects” for dissection. I was aware of some of this history, especially the story of William Burke and William Hare, two Irishmen in Edinburgh who murdered 16 people in 1828 to sell to the anatomist Robert Knox. As I investigated further, I realised this was just the tip of the iceberg.

I began searching for cases of Irish bodysnatching in newspapers and archives, expecting to find a small number of incidents spread out over time and place. To my surprise, however, I found that in the 1820s and 1830s medical students and porters relentlessly stole corpses from the same Dublin graveyard, later hiring gangs of murderous “resurrection men” to do the job for them. Some medical schools even participated in a ghastly export body trade which brutalised the dead and their relatives, especially the poor of Dublin. The sheer scale of bodysnatching in Ireland, the use and abuse of thousands of nameless dead, is shocking enough, but worse was the callousness of medical professionals who failed to see this as anything more than a supply issue.

The key difference between then and now is that there was no culture of body donation and the principle of consent was not taken seriously. Dissection was not always a core part of undergraduate medical education, but by the late 18th century it was believed that the extensive anatomical knowledge gained from dead bodies was the key to understanding the diseases and injuries of living bodies. The problem was that, apart from the small number of corpses legally provided to surgeons from the gallows – as per the Murder Act of 1752 – there was no mechanism, nor desire, for donating bodies for the advancement of medical science. The reasons for this were partly religious, as people were worried that dismemberment would have spiritual consequences, but mostly a widespread awareness that bodies were treated with disrespect in the dissecting rooms. This was understandable as, after being disinterred, purchased, divided, butchered, dissected and handed around, the remnants of the body would be dumped in a communal pit, or thrown in the river, perhaps accompanied by the flesh of the latest executed criminal. Dissection represented, in the words of the Murder Act, “some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy”.

So anatomists were long associated with the body trade, whether from the gallows or the graveyard, but popular antipathy towards them became stronger in the 1820s just as Dublin’s medical schools were growing in size and promising to provide students with abundant “subjects” for dissection. There is evidence that there was an influx of English medical students to Dublin around this time as procuring bodies for dissection elsewhere became more difficult and expensive: in Dublin the average price for a corpse in 1828 ranged from half a crown to 10 shillings (12.5 to 50 pence), whereas in Edinburgh in the same year Burke got £7-10 for his fresh corpses. With its high mortality rates and large population of paupers, Dublin had an international reputation for cheap subjects. Anatomy teachers expected medical students to dissect up to three bodies during a winter session and, as there were an estimated 500 dissecting pupils in Dublin in 1829, this implies that some 1,500 bodies were needed annually – as fresh as possible – to meet seasonal demand.

This enormous traffic in corpses simply could not have operated without a sophisticated system of exhumation, transportation and distribution. A web of corruption connected the supply chain from grave to dissecting table, and this included policemen, who could easily be bribed, and magistrates who tended to be lenient towards any resurrectionists unfortunate enough to be captured by the mob. More often than not, the RCSI cooperated with other medical schools in ensuring a share in the spoils. The “golden age” of Irish medical education, in other words, was built upon the organised crime of bodysnatching.

The principal source of bodies for the medical schools was Bully’s Acre, a large burial ground just outside Dublin city centre where paupers traditionally interred their dead freely. Nearby pubs provided mourners with picks and shovels, while spotters noted where the graves were dug so they could be “raised” later that night. It was an open secret that during the months of the winter teaching session Bully’s Acre would be raided most nights by medical students under the guidance of their teachers. They knew they were breaking the law because, although it was not an indictable offence to be caught with a corpse, the act of disinterring (as well as the theft of clothing and other forms of property) counted as a misdemeanour.

The evidence for medical criminality is not hard to find. The archives of the RCSI reveal that porters and resurrectionists were employed to obtain bodies for the college, so much that by 1828 there were high-level discussions about the “system of Warehousing”. Further details were out in the open. Writing in the British Medical Journal in 1879, the renowned surgeon and MP Sir Dominic Corrigan wrote about his bodysnatching days in Dublin in the 1820s. Corrigan disclosed how he used to bribe the watchman before his gang used a grappling iron to break open the head of the coffin. A rope was then inserted around the neck of the corpse and it was dragged out. This practice was repeated until at least four bodies were gathered.

“What added to the ghostly and ghastly character of the moonlight scene”, wrote Corrigan, “was that the bodies were stripped stark naked, for the possession of a shroud subjects us to prosecution.” They then placed their cargo in a carriage and swiftly headed for one of the schools – the RCSI, Trinity College Dublin or Kirby’s school on Peter Street. Occasionally, Corrigan continued, “some meddlesome young watchman, not fairly bribed, or busy passer-by, raised a warning shout, and we had to fight our way for half the length of a street”. Given such gruesome behaviour towards the pauper dead, a backlash was only to be expected.

As the demand for corpses increased in the 1820s, so too did their value. Greater levels of bodysnatching activity led to vigilante operations at graveyards, with parish officers recommending that armed watchmen be installed to protect the recently dead. As things took a darker turn, the medical schools outsourced the practice to professional resurrectionists – or “sack ’em ups”, as they were popularly known in Dublin. Bodysnatching was traditionally thought of as a small-scale and discreet practice. Yet judging by the newspaper accounts, court records and government documents I examined, there was something of a resurrectionist crime wave between 1827 and 1832. Dublin’s bodysnatching gangs operated in large numbers – sometimes as many as 50 men (I have traced the names of 20). They were heavily armed and willing to shoot anyone who interfered in their trade. We know from newspaper reports that there were almost weekly confrontations and battles between the resurrectionists and the watchmen.

In 1827, Surgeon Ellis, a partner in Kirby’s school, saved the lives of two resurrectionists who were being hunted by a mob. He hid them in his stables, but “so closely was he watched by his neighbours that it was only on the pretext of carrying food to his dogs that he could bring them the necessaries of life”. In the same year, Luke Redmond, a porter at the RCSI, was caught bodysnatching and ducked in the River Liffey. His widow applied to the College Council for £10 as “some small relief” after he died “in the service of the College”. The application was refused (although during the same meeting the same amount was allocated for temporary stands to house the anatomical preparations of some reptiles).

There were major shoot-outs at the Merrion graveyard in 1828 and Glasnevin cemetery in 1830, during which attackers and defenders were seriously injured. Things became so bad that Sir John Byng, the commander-in-chief of Ireland, established an armed militia – the “St John’s Humane Society” – to protect Bully’s Acre. These guards increased the levels of violence and a well-known resurrectionist named William Byrne was shot with a “brass barrelled blunderbuss”. Byrne was lucky to survive, having his arm amputated at the shoulder, and was afterwards known as “Fisty” Byrne. Yet a letter in the papers of the chief secretary’s office (the Irish executive) reveals that by 1831 these guards had gone rogue and become bodysnatchers themselves, refusing to surrender their weapons. There is further evidence from newspaper records that at least two watchmen and five resurrectionists were killed around this time, while another “sack ’em up” was whipped with a “cat-o’-nine-tails made with wire”.

In 1828, a parliamentary select committee discussed ways of reforming anatomical education. In his remarkable evidence to the committee, Trinity College Dublin anatomist James Macartney blamed “religious prejudices” about the sanctity of the dead in Scotland for encouraging resurrectionists to look to Dublin for undefended corpses. Although his own hired gang terrorised Dubliners in their hunt for bodies, Macartney told MPs that popular outrage was mostly caused by new operators who entered the market to export bodies at double the price to Edinburgh and London. At the same time, the council minutes held in the archives of the RCSI reveal that an investigation was established to ascertain if its porters were connected in this export trade. In a scandalous finding, it reported that a new gang called the “High Pricemen” were permitted by a porter named Dixon to use the college as a distribution warehouse, something it was predicted that, if not controlled, would “sap [the] very foundations” of the institution.

Dixon would not name the leader of this gang, but he was Wilson Ray – a native of the Isle of Man and member of the Royal College of Surgeons, London, who moved to Dublin in 1827. Ray took advantage of the new faster steam packets on the Dublin to Greenock route to cram corpses into barrels or piano cases and have them delivered – half-decomposed – to middlemen waiting on the River Clyde for transport to Glasgow. Ray also probably encountered agents sent by Robert Knox, seeking to sample cheaper Irish subjects. This gory trade was exposed several times when “offensive smells” were reported by quay porters in Dublin. When he was arrested in 1829, Ray summoned Dublin’s leading surgeons in his defence. “Good God!” he said in court, “If I am guilty of any crime, then those gentlemen are equally guilty, and all those who procure subjects for anatomy schools.”

Reforms were coming in the shape of the Anatomy Act 1832, which provided anatomists with lawful access to unclaimed corpses from workhouses, prisons and other institutions. However, it is depressing to note that the Irish lobbying effort focused less on finding more ethical sources for bodies than with bemoaning the impact Ray’s trade was having on their existing procurement practices. It seemed that this “carcass-merchant” had avoided Bully’s Acre at first, but he then began to outbid the medical schools for the corpses sourced there. This led to a reduction in supply which encouraged the resurrectionists to enter into a “combination” (trade union) and use the shortage of corpses in Dublin to raise prices. Market forces and the demands of medical education trumped respect for the dead and the sacks continued to be dropped off at back entrances to medical schools in the city.

Things have certainly changed for the better in Irish medical education since the Anatomy Act. When I went on a tour of the RCSI this summer, we were told that photography was forbidden at the entrance to the anatomy room out of respect for the dead. Students, the head porter said, are taught that bodies donated for anatomical purposes are their “first patients”, and they must never breach the confidentiality of this relationship. Meanwhile, at Glasnevin cemetery, not far from a watchtower that once protected the cemetery from the invasions of the bodysnatchers, a plot and headstone commemorate the remains of those who now willingly donate their bodies to the Dublin medical colleges.

So the principles of consent and the decent treatment of human remains now seem to be firmly established in Dublin. Yet, as recent events in Arizona remind us, one does not have to look far to see how disrespectful treatment of dead bodies can still raise acute issues for medical science and education today.

Shane McCorristine is a lecturer in modern British history at Newcastle University. His latest book is The Spectral Arctic: A History of Dreams and Ghosts in Polar Exploration (2018).

后记

Print headline: Bodysnatching in the name of science