Last year’s votes for Brexit and Donald Trump were greeted with predictable howls of horror from universities in the UK and US. For many people associated with higher education, the brand of right-wing populism that propelled both votes is anathema to their progressive and internationalist values.

For instance, nearly a third of respondents to a recent YouGov survey carried out in early January for the UK’s University and College Union said that they already knew of academics leaving the UK, while 44 per cent knew scholars who had lost access to funding as a direct result of Brexit. Among European Union nationals working in the UK, more than three-quarters stated that they were more likely to consider leaving UK higher education since the referendum. This level of discontent is borne out by a more recent Times Higher Education online poll (see end box), and is also very common among UK nationals. And although fewer US academics took part, those who did expressed a similar willingness to quit the US in the wake of Mr Trump’s election.

“We know that many of our academic colleagues from other EU countries are deeply concerned about the [UK’s] decision to leave the EU and what it means for their future here,” Keith Burnett, vice-chancellor of the University of Sheffield, tells THE. “These talented teachers and researchers are vital to our universities and many of them feel personally undermined by the nature of the debate during and since the referendum. I do know that some are considering their future.” He is particularly worried about young academics “who have yet to establish their life in a chosen country – [their] choices now may have an impact for years to come”.

In order to stop disillusion prompting a mass exodus, Burnett would like to see the UK government sending “a quick, clear, reassuring signal to our wonderful international academics that their investment in the UK is, and will continue to be, valued and prioritised”.

“The UK is still a very attractive place for scholars around the world because of our concentration of leading universities with a global reputation,” he continues. But if we in any way undermine the advantages of working here, particularly as overseas staff find that a weaker pound is worth less in their own countries, the attractions of the UK may decline as other nations seek to attract talent globally,” he concludes.

Explore our database of university jobs

Anton Muscatelli, principal and vice-chancellor of the University of Glasgow, says that his institution is “ensuring that we keep our academic colleagues informed on how Brexit may impact on future funding opportunities. We are reassuring colleagues that...we are seeking to influence UK government and EU institutions on the importance of European funding for UK universities, and the key role that the UK plays in the European Research Area.”

In the US, the situation is a little less clear. A survey of more than 1,600 professionals and academics by biotechnology publication Genetic Engineering & Biotechnology News, a day after Mr Trump’s election, found that about 47 per cent believed that foreign-born researchers educated in the US would be more likely to leave during the Trump presidency.

But although there is evidence that a “Trump effect” is making the US a less attractive destination for international students, many seem less convinced about the dangers of large faculty losses and the need for universities to take urgent remedial action.

According to Philip Altbach, research professor and founding director of the Center for International Higher Education at Boston College, “there is a huge amount of grumbling among academics about Trump and the future, and mumbling about the possibility of moving out of the country. But I doubt very much if American citizens would look for academic jobs in other countries. That is a difficult process with many implications for families, as well as professional life.” But he does think it likely that non-US citizens working at US universities will “actively look for a more welcoming environment elsewhere”.

“The US academic and scientific communities are now actively struggling against Trump’s initiatives, trying to assure international students and staff that they will be protected by their universities as much as possible,” he says. “The major organisations representing US higher education and science, such as the American Council on Education [and] the National Academy of Science...have issued statements and are lobbying actively in Washington.”

More forthright was the response of Mitch Daniels, president of Purdue University and a former Republican governor of Indiana. When asked by THE whether he thought that US academics would leave during a Trump administration, he said: “I would expect [it to have a] close to zero effect and [I] have not seen any evidence so far.”

John Elmes

‘If you’re in a British university and wanting to move, you’d just think you’d landed in a sunnier place with a beach’

Australia might seem like an obvious alternative destination for UK- and US-based academics.

Apart from its sunny climate and English-speaking population, other pull factors include some highly ranked universities (eight in Times Higher Education’s World University Rankings 2016-17), academic systems very similar to the UK’s and a recent government investment of A$400 million (about £250 million) a year in scholarships and fellowships to lure high-achieving researchers from overseas.

At the University of Wollongong, says its vice-chancellor Paul Wellings, “8.9 per cent of my academic staff are from [the UK] already. From the US, it is 1.5 per cent, [equating to] just over 10 per cent of [the total].” Indeed, Wellings himself is an expat: he moved to the coastal city about 50 miles (80km) south of Sydney at the beginning of 2012, having previously been vice-chancellor of the UK’s Lancaster University. He anticipates that the number of people following in his wake may well increase in the coming months and years, and he is keen to talk up Wollongong’s willingness to receive them.

“We’ve shifted our strategy away from specific job adverts,” he explains. “Through the THE, we’ve run a series of advertorials saying: ‘Hello, we’re here. If you’re thinking about moving, here’s an outstanding institution on the eastern seaboard of Australia.’” Nor, he notes, is his the first Australian institution to run such adverts, and he would be “amazed” if other universities were not looking at doing likewise.

“If you’re in a British university and wanting to move, you’d just think [when you arrived here that] you’d landed in a sunnier place with a beach,” he jokes. “The pitch for a university like Wollongong is that location. The target group we’d be looking at is the early to mid-career people who are established but not sure what their long-term future is.” That is, people who have “at least 20 years” of their working life ahead of them.

Meanwhile, on the day after last November’s US presidential election, there was a significant spike in traffic to the THEunijobs website – which lists jobs at Australian universities – from the US, with job listings receiving 39 per cent more traffic than the average for the prior three months.

David Morrison, deputy vice-chancellor for research and innovation at Murdoch University in Perth, says that about 60 per cent of the people who made the shortlist for a recent job at his institution were from the UK, and there were also “increasing numbers from the US” applying to positions. Recruitment of such academics was “certainly something [that Murdoch had] talked about” at a senior level, especially in light of the uncertainty surrounding the UK’s access to the Horizon 2020 funding programme when Brexit occurs. Morrison notes that research funding in Australia is also very tightly rationed; the grant success rates for the country’s National Health and Medical Research Council are only 13 to 15 per cent, he says. But he believes that, faced with a choice between two countries – the UK and Australia – where funding is “relatively difficult” to obtain, “you might opt to move to Australia” on account of its superior “living conditions”.

UK-based academics may also crave Australia’s lighter-touch version of the research excellence framework, known as Excellence in Research for Australia – on which much less institutional funding rides. But scientists may be less keen on being judged on research metrics alone. And Wellings is sceptical that swapping the REF for ERA will be much of a lure. “[Academics] might see ERA as less onerous, but on the other hand there’s less opportunity to shine,” he said.

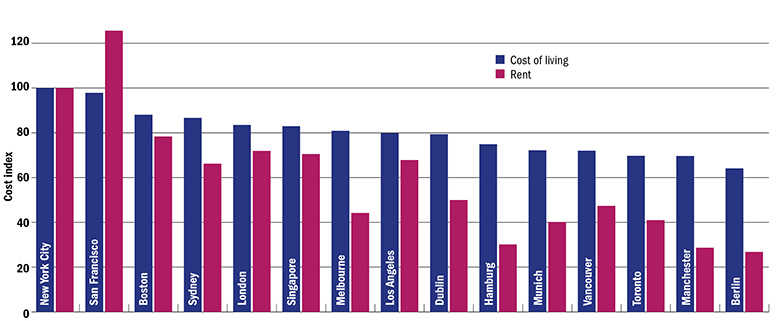

Moreover, moving countries, he notes, can be a “dislocation to academic momentum”. And, in the case of Australia, it is also important to be realistic about quality of life, given the “eye-watering” house prices in major cities such as Sydney and Melbourne, he cautions.

John Elmes

‘Hiring faculty who do not speak German always causes some problems’

Germany has a long history of successfully poaching top academics from overseas, and Brexit offers potentially rich pickings from the UK. The Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, whose modern history began in 1953, offers a range of fellowships and awards to conduct research in Germany; Humboldt professorships, for “internationally recognised” leaders in their field, are worth up to €5 million (£4.25 million) over five years.

“We do expect an increasing number of applications from Britain” for this year’s professorships, says Enno Aufderheide, secretary general of the foundation, which is currently in discussion with the German government and parliament about increased funding to take on more researchers from the UK. After the Brexit vote, “we might need special resources to take advantage of the opportunity”, he says. German universities have also reported better prospects for hiring from the UK, he explains.

But he is keen not to sound gleeful at the prospect: the organisation as a whole is “extremely sad” about the prospect of Brexit. “I wouldn’t say we are hoping for anything; we are hoping the Brexit process will be reversed,” he says.

Aufderheide thinks that researchers from the rest of the EU are more likely to decamp from the UK to Germany than British citizens. The atmosphere in the UK is driving foreign researchers away, he says. “This is what I hear from people teaching in London, Oxford or Bristol,” he says. “They are harassed on the open street, and if they speak a foreign language they get a negative reaction.”

Humboldt opportunities, while prestigious, are probably too few in number to enable a mass exodus: in 2015, it distributed about 900 fellowships and awards globally, and granted just 10 professorships.

Poundstretchers?: cost of living and renting around the world

Source: Data taken from Numbeo on 31 January 2017. Numbeo crowdsources information about costs in cities across the world. Indices are a measure against New York, which is 100.

But Germany also boasts networks of well-endowed and highly internationalised research institutes, such as the Max Planck Society and the more industry-focused Fraunhofer institutes, explains Uwe Brandenburg, managing partner of CHE Consult, a higher education consulting firm.

“These research institutions have huge budgets: we are talking billions [of euros],” he says, adding that they can afford to provide “extremely attractive research conditions” from their own budgets, without researchers even having to win external grants. Communication in these centres is normally done in English because there are so many international faculty, he explains.

But moving to a German university would pose a greater language barrier. “Teaching in Germany is still mainly in German,” says Aufderheide. “Hiring faculty who do not speak German always causes some problems” for universities, who will therefore need a “special motivation” to employ academics who are not yet fluent in the language. The German system also has relatively few secure academic positions below the level of professor, he cautions, meaning that “the level of security for young people is lower than [in] other countries”.

Still, with no equivalent of the research excellence framework and generally higher grant success rates, Germany might sound like a tempting alternative for academics sick of bureaucracy in the UK.

But to actually reach research paradise in Germany, both Aufderheide and Brandenburg emphasise, you really do have to be at the top of your field. “It’s hard to get into the system,” says Brandenburg. “If you are an average researcher with nothing specific to offer, then the chances are extremely slim.”

David Matthews

‘I think we’re seeing the benefits of a good funding environment, and – to be frank – no research excellence framework’

UK-based scientists who feel “uncertain or unloved” should look across the Irish Sea. This was the advice given by Mark Ferguson, the director general of Science Foundation Ireland, last July when presenting the annual report of the Republic of Ireland’s major science funder. The former University of Manchester academic, who is also the Irish government’s chief scientific adviser, himself made the voyage from Holyhead to Dún Laoghaire in 2012.

Then, in October, the Irish government pledged to invest an unspecified amount of taxpayers’ money in attracting researchers “in the context” of Brexit. And at the end of November, Ireland’s Higher Education Authority released a report titled Brexit and Irish Higher Education and Research: Challenges and Opportunities, which calls for the republic to “act as a talent magnate, attracting the best...academics and researchers...[and to] support all international...staff and researchers seeking to re-locate to Ireland”. There are signs that this open-arms policy is already attracting scholars. At University College Dublin the proportion of job applicants from the UK rose from 21 per cent before the referendum to 28 per cent after it, across all disciplines.

“We’ve had many enquiries from academics in the UK…expressing their desire to look for alternatives post-Brexit,” Andrew Deeks, president of University College Dublin, tells Times Higher Education. “These are both [academics from] mainland Europe working in the UK [and] native UK academics who aren’t happy with the way the country’s going.”

His institution is considering a “concerted campaign” – while trying to avoid “making it look like we’re taking advantage of the UK’s woes”.

Patrick Prendergast, president and provost of Trinity College Dublin, notes that his institution already has a programme to attract top global professors, and he expects that it “won’t need very great revising to be suitable for academics who want to leave the UK for Brexit reasons”.

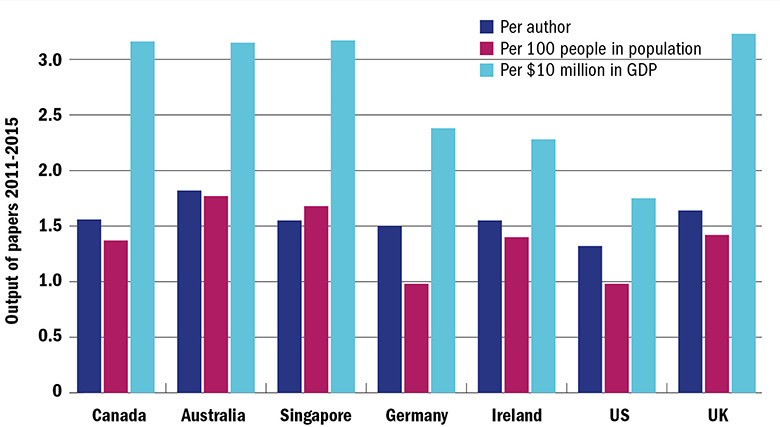

Bang for buck: research productivity

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool, World Bank.

Among the obvious draws for those wanting to relocate, according to Deeks, is Ireland’s commitment to research investment, maintained even during the recent period of austerity.

“Although there were many cutbacks, research funding was not cut,” he says. “I think we’re seeing the benefits of a good funding environment, and – to be frank – no research excellence framework. We don’t spend a lot of time, as UK universities do, analysing, strategising in terms of the REF, so academics can get on with the research and generating the results, writing the papers.”

Prendergast agrees that the republic’s “high level of investment” in science and engineering is appealing, but puts the main stress on the “unequivocal, clear-cut commitment” Ireland has to its EU membership. Besides the €154 million (£133 million) the SFI invested in research in 2015, researchers it supports leveraged a further €130 million from non-exchequer funding, of which €79 million came from the EU’s Horizon 2020. This represents a threefold increase since 2014.

Post-Brexit, “Trinity will become the highest-ranking English-speaking university in the EU”, Prendergast notes. “Of course, many other universities speak English as their working language, but Ireland is an English-speaking country, so those who want to bring up their children in such a country, while being in the EU – which may be American academics and UK [ones] as well – may think Ireland is a good place.”

Possible disadvantages include a feeling that the Irish government has put too much emphasis on commercial applications when funding research in recent years. In 2012, the Irish government announced that public research grants would be confined to 14 priority areas largely chosen for commercial reasons: a policy that one Irish academic decried in THE in 2015 as “funding apartheid”.

Deeks suggests that this policy should be seen in the context of the austerity period after Ireland’s economic meltdown in 2008, when research that could lead to economic benefit was understandably prioritised.

“There’s been a gradual swing back,” he points out. “There’s still a lot of work to be done, but...things are improving. There is a return of funding to the Exchequer, and there’s been recognition that research funding is needed in both applied areas and areas of blue sky, so we have seen a rebalancing.”

Another possible worry is creeping bureaucracy. Although there may be no Irish REF, Trinity has worried staff recently by introducing its “Principal Investigator Quantitative Analytics” (PIQA) scheme, which ranks academics on their research output. John Walsh, chair of Trinity’s branch of the Irish Federation of University Teachers, said in Ireland’s University Times in February that the union would “object to anything that involves an approach” like the REF.

If PIQA’s pilot year is deemed a success by senior management and individual benchmarking of academics based on their research becomes the norm, the lure of the Emerald Isle may just diminish a little.

John Elmes

‘We have got a very-science friendly government run by Justin Trudeau’

Canada has long been the refuge to which liberal celebrities disappointed by US election results threaten to flee. But since Donald Trump’s victory last November, and the earlier Brexit vote, there really has been a noticeable uptick in interest from both foreign students and faculty, says Santa Ono, president of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

“In our own data, we see significant spikes…in actual applications [from students] and from faculty,” he tells Times Higher Education.

UK- and US-based academics have slightly different motivations for emigration. US-based students and academics, who “tend to be on the liberal side”, simply feel more comfortable in Canada because of its more progressive values, he explains. On the other hand, UK-based faculty are more focused on the “bottom line”, worrying about the loss of EU research funding and falling tuition fee revenues from EU students post-Brexit.

So what does Canada have to offer academic émigrés? “We have got a very-science friendly government run by Prime Minister [Justin] Trudeau,” says Jim Woodgett, director of research at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, who moved from London to Canada in 1992 but regularly returns to the UK to sit on review panels.

Of course, the country that elected Trudeau at the end of 2015 also voted for his predecessor, Stephen Harper, who was considered to be extremely hostile to science, not to mention the controversial, crack-smoking Toronto mayor Rob Ford. But Canada does seem to be going through something of a research renaissance under Trudeau’s Liberal Party. The new government has announced C$2 billion (£1.2 billion) of extra funding for university infrastructure over the three years beginning in 2016-17. It has also pledged almost C$100 million a year extra for research councils, and has tried to patch up relations with scientists, who felt muzzled under the previous Conservative administration. Canada has also overtaken the UK as the most attractive destination for EU students, according to a recent survey.

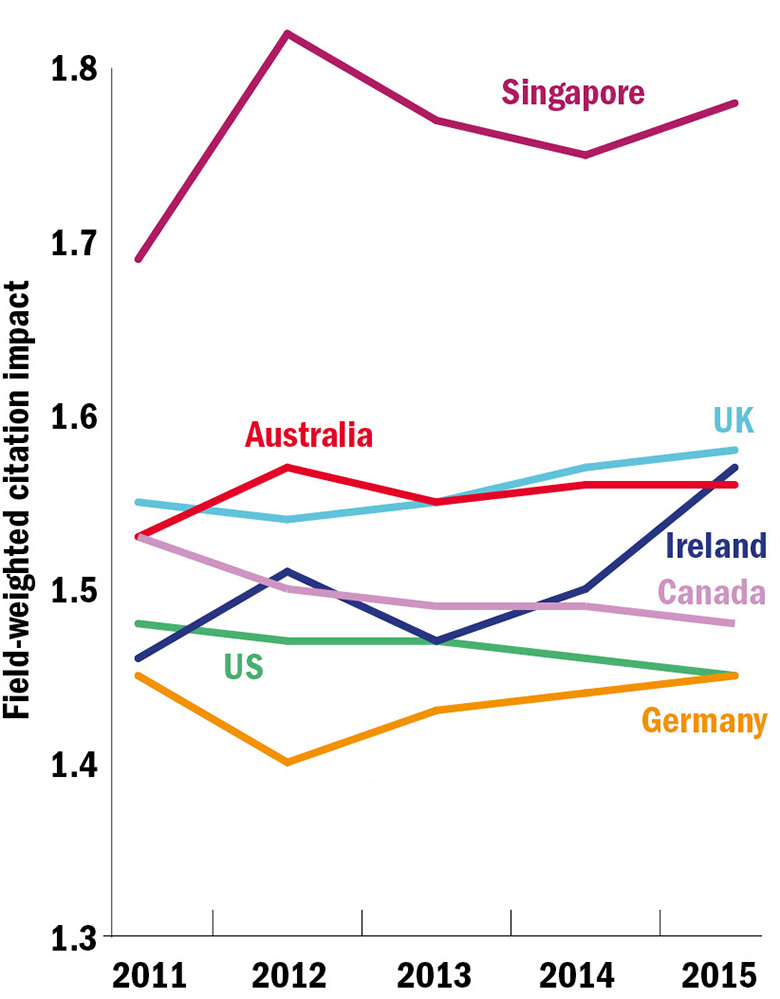

High impact: trends in quality

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool. Field-weighted citation impact is a measure of citation impact that takes into account countries’ relative performance in different discipline areas. The global average is 1.

There is no research excellence framework-style assessment burden in Canada, says Woodgett, and he judges that Canadian scientists are better paid than their British counterparts. Those running universities tend to be paid less, however; “we tend to put more emphasis on the people actually doing the work”, he thinks.

Rather like Germany, Canada has specific schemes to tempt top researchers to its shores. The Canada Excellence Research Chairs give universities up to C$10 million over seven years to attract academics and their teams to the country. Since the shocks of Brexit and Trump, there has been an uptick of interest, primarily from the UK, says a spokesman.

The University of British Columbia is also trying to capitalise on political uncertainty in the US and UK, says Ono. “We are acting on it. We are in the midst of trying to recruit internationally renowned individuals” who have become more likely to leave since the elections of 2016, he says.

But there are drawbacks to working in Canada. Woodgett warns that applying for research grants, at least in health research, has recently been a “disaster” because of a reorganisation at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, which had proposed replacing face-to-face peer review meetings with a purely online system.

And while Canada may be large and mostly sparsely populated, academics harbouring dreams of a palatial family home may be in for a shock. Rocketing house prices have outraged citizens, particularly in Vancouver, where, in 2015, the Twitter hashtag #donthaveonemillion took off to highlight the unaffordable price of an average home in the city.

Ono, who previously worked in London, points out that the British capital is still more expensive (see bar chart, page 39). The problem is one of expectations, he thinks: as a lecturer at Imperial College London or University College London, “you don’t expect to live in a detached house with an acre of land”, he says. In Vancouver, “people do afford flats…but some of them want to have a yard and four bedrooms, and that’s become more difficult”.

David Matthews

‘What Donald Trump says about Muslims you could never say here’

Singaporean universities have zoomed up the international rankings in the past decade as the city state has invested heavily in education to secure its economic future. It has only six universities, so can hardly absorb a vast influx of foreign researchers. But according to Arnoud de Meyer, president of Singapore Management University, there has been noticeably more curiosity about research opportunities in Singapore from UK and US academics since the votes of 2016.

“Nobody will say it is because of Brexit or because of the uncertainties in the United States about what the new administration will do to higher education,” he says. “But you just see that people are waiting and seeing what is happening in the UK and US and, in the meantime, looking at opportunities in this part of the world.” So far, he says, more interest has come from the US than the UK.

Singapore is still investing heavily in research, although it is not ratcheting up spending quite as exponentially as it did during the 1990s and 2000s. In 2015, it committed another S$19 billion (£10.6 billion) over five years, S$3 billion more than in the previous five-year plan. In the same year, it set up a social science research council, meaning that the discipline will no longer be the “poor cousin” of other subjects, according to de Meyer.

The promotion and tenure system in Singapore is very similar to the US, explains de Meyer, and there is no centralised assessment of individual academics’ research or teaching. Instead, universities’ overall performance is assessed every five years by an international panel.

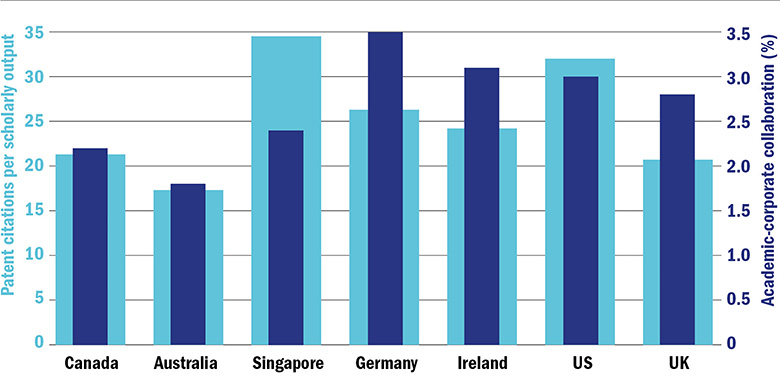

Well connected: industry links and influence

Source: Elsevier’s SciVal tool.

Notes: Academic-corporate collaboration = proportion of country X’s papers co-authored with industry. Patent citations per scholarly output = the average number of citations from patents per 1,000 publications published by country X in year Y. Data are drawn from European Patent Office, Intellectual Property Office, Japan Patent Office, US Patent and Trademark Office, World Intellectual Property Organisation

Still, Singapore is dogged by a few reputational problems, fair or not. First, that it is a slightly dull place to live (when Times Higher Education visited the city in 2013, Western expat academics tended to be slightly defensive about how long they had lived there, often citing convenience).

Fifteen years ago, “it was quite boring”, acknowledges de Meyer. But now there are good concerts, theatre and art exhibitions, he says. “It lives up to any comparison to any second-tier city in the UK”, he says, by which he means “any city but London”.

Second, there have also been occasional rows about academic freedom in Singapore’s authoritarian democracy. “The government here does not tolerate anything that would incite religious or racial tension...That is an area where we are more careful in doing research,” says de Meyer. “What Mr Trump says about Muslims you could never say here.” But, for example, research can be openly done on what Singapore’s different ethnic groups think of each other, he says. Some academics practise “a little bit” of self-censorship, but de Meyer thinks that this is probably unnecessary.

And, finally, Singapore is expensive: data (see bar chart) show that its cost of living is almost on a par with London’s. Universities often have their own housing or assistance programmes for faculty, says de Meyer. However, “the real cost would be education for children”, he explains. “For most foreigners, you end up sending children to international schools, which have a fairly high tuition fee. We sponsor some of that, but it remains a significant cost.”

David Matthews

Itchy feet?: THE’s survey of UK and US academics

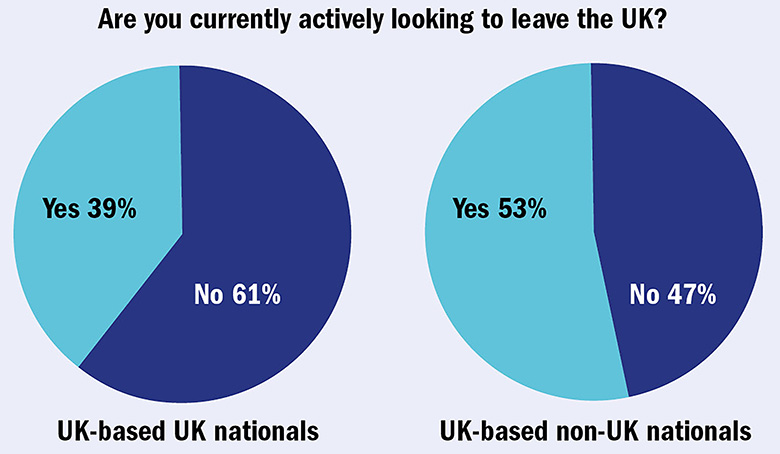

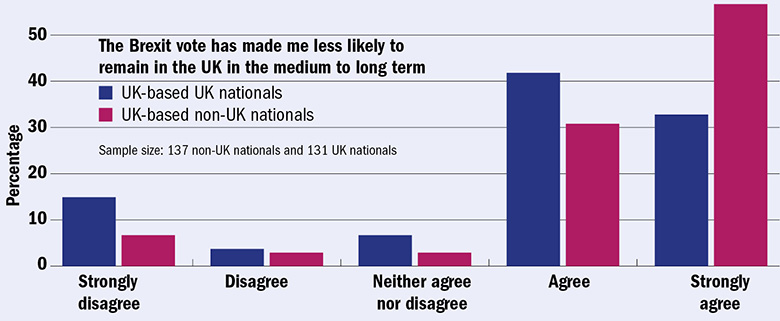

Many academics working in the UK are seriously hoping to pursue careers overseas as a result of Brexit, a new Times Higher Education survey indicates.

Of 131 UK nationals who responded to the online survey, carried out in January, 39 per cent are actively looking to leave the country, with 74 per cent agreeing that Brexit has made them more likely to leave in the medium to long term.

Although people particularly exercised by Brexit are likely to be overrepresented among the respondents, who were self-selecting, such figures are likely to worry UK university leaders.

While there are common concerns about the threats to research funding that leaving the European Union may incur, there is a particular objection to the hostile cultural climate that the rhetoric around Brexit has engendered.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, anti-Brexit feeling is even higher among non-UK nationals in the UK. A startling 53 per cent say that they are actively looking to leave the UK, and 88 per cent say that Brexit has made them more likely to do so in the medium- to long-term. Once again, objection to the cultural climate is the main reason, although fears about their immigration status are also cited by nearly 40 per cent of those inclined to leave.

One respondent likens the current “anti-intellectual climate” to the 1930s, claiming that we’re in an “even bigger crisis than [former UK prime minister Margaret] Thatcher managed to unleash”.

A non-UK national, who is “already committed to leaving”, describes the Brexit vote as “really shocking. I chose to immigrate to the UK, and found it a fantastic environment to do research in, and also to attract researchers and students. I fear that so much good work is being undone and that the government [does not understand] how much damage they are doing to the university sector, which brings so many economic benefits to the country.”

A non-UK national cites “diminished psychological safety” as a reason to leave, while a French academic, resident for 28 years in the UK, says that the “societal climate” of the UK has changed for the worse. “Most of my EU friends and colleagues agree that we did not come here for the weather, food or quality of life. But we liked the way the UK seemed to embrace ‘others’, and the diversity and ease with which we all ‘melted’ [together] was my number one reason for being here,” the academic says.

Another academic ominously speculates that this familial feel was all just a veneer: “Although I am now a UK national, I migrated here. The current rhetoric and uncertainty, the lack of accountability and due process and the emergence of right-wing bigots and racists has made me realise that I never knew this country at all.”

The data also offer some intriguing insights into where UK academics driven out by Brexit might choose to go. Top of the list for UK nationals is Canada, followed by Germany and Australia. For non-UK nationals, Germany is the top destination, followed by Canada and “other European nations”, including Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden.

Although US-based academics responded to the survey in much smaller numbers, they express a similar discontent with the US since the election of Donald Trump, with objections to the more hostile cultural climate cited overwhelmingly by both US nationals and non-nationals. For US nationals, anglophone nations feature prominently among their alternative destinations. Top is Canada, followed by Australia, New Zealand and the Republic of Ireland. Non-US nationals also prefer Canada, followed by Germany and Australia.

One respondent said: “It is unethical to continue teaching and working in Trump’s America.” Another, a US citizen who has worked in the UK for 16 years, is disillusioned with both nations. “I have already started to apply for jobs in Norway, Germany and Ireland,” the academic says.

John Elmes

后记

Print headline: I’m an academic...get me out of here!