The University of Tasmania may be small by Australian standards, but it seems to be omnipresent in the country’s southern island state. Turn any corner and you stand a good chance of bumping into the university’s red lion logo, not just in Hobart and Launceston, the island’s two largest cities, but also at outposts such as the northern maritime hub of Burnie, the faded western mining town of Zeehan and the industrial Hobart commuter town that goes by the unlikely name of Cambridge.

Turn on the radio and it is not long before UTas academics enlighten you on subjects ranging from state politics to the perils of artificial intelligence, the fortunes of a hand-reared brood of critically endangered red handfish and the industrial chemicals in the bloodstreams of the fairy penguins nesting outside Burnie’s new Cradle Coast campus.

UTas is a big fish in a small pond. Tasmania may be about the size of Sri Lanka, but that amounts to less than 1 per cent of Australia’s landmass, and it is home to little over half a million of Australia’s nearly 26 million people.

Outside the three main urban areas – the Derwent River estuary around Hobart, the Tamar Valley in the central north around Launceston and a string of north-western coastal towns, including Burnie – the state is, in essence, a scattering of fishing ports and rural hamlets separated by farms, mountains, forests and one of the world’s largest temperate wildernesses.

For years, Tasmania has wrestled with Australia’s sparsely populated Northern Territory for the dubious honour of having the country’s weakest economy. It has the slowest population growth and second-highest unemployment rate of the eight Australian states and territories. Judged on a cocktail of factors – economic growth, retail spending, construction, equipment investment and so on – Tasmania performs the worst of any jurisdiction.

And while the university (Cradle Coast campus, above) may be big in Tasmania – it employs more than one in every 100 Tasmanian workers, not counting casual academics – Tasmanians are not particularly big on higher education. Their island has the lowest proportion of degree-educated adults of any Australian state or territory, and the pipeline of future students does not look promising given that Tasmania has the nation’s fastest-falling population of school students and easily the lowest proportion of adults with completed high school qualifications.

“People I went to school with [tended to] get an apprenticeship or just go get a job,” says Tony Beckett, a Launceston native who is now president of the university’s National Tertiary Education Union branch. “People who wanted to go to university went…to Melbourne [or] Sydney. I don’t know how much that’s changed. I suspect if students are wanting to go to university, Tassie [still] isn’t necessarily the place they’re thinking of.”

Placed alongside another four Australian institutions in the 251-300 range in Times Higher Education’s latest World University Rankings, the University of Tasmania is far from the country’s lowest-ranked institution. Yet the institution’s leaders are all too aware of the lack of local demand for higher education and have responded by embracing a novel strategy. If the people will not come to the university, the idea is to take the university to the people: put it where Tasmanians go to work, shop, play and recuperate.

In Burnie, for instance, UTas’ suburban campus was abandoned and operations shifted three kilometres to the A$52 million (£27 million) garden-roofed Cradle Campus right on the coast, a stone’s throw from the town’s main beach and shopping strip. The university has also spent A$4 million on the latest makeover of an adjacent former paper mill that it leases from the local council and uses as a technology and innovation hub. To maintain a welcoming air, the campus is open most days of the year and has a publicly accessible library and electric vehicle-charging facilities available for community use.

UTas’ deputy vice-chancellor Ian Anderson, a former deputy secretary of Indigenous affairs in the prime minister’s department, says he was uncertain about the need for regional campuses before joining the university in early 2023. He no longer harbours such doubts, noting that before Burnie had its new nursing clinic, the cost of undertaking compulsory placements alone would have rendered the discipline unaffordable for many locals.

He says that universities need to focus, both inside and outside the classroom, on how to better “curate social mobility”, noting that “people underestimate the cultural and emotional dissonance” that a first-in-the-family student faces on contemplating higher education.

Vice-chancellor Rufus Black says that while UTas has few international comparators, Scotland’s University of the Highlands and Islands perhaps comes closest; both combine the lure of natural beauty with the challenges of remoteness, high social need and low economies of scale.

“There are so many people in…our different communities who can’t afford to leave them because of their jobs, because of their care responsibilities, because of the financial challenges,” Black says. “If we’re not present, people can’t access higher education. We…have to provide multiple locations, the full breadth of courses [and] research intensity for the state. Trying to make that work financially…is completely different to a metropolitan university model.”

Black says running the northern campuses sets the university back a net A$60 million a year. “That’s the cost, if you like, of being present: increasing lifespans in those communities, raising average incomes, providing them with doctors and nurses and social workers and psychologists they wouldn’t otherwise have,” he says.

The Australian Universities Accord’s final report, published in February, is very focused on widening participation and recommends strengthening financial support for regional universities educating non-traditional students, who typically need more help than traditional students. In many ways, UTas is the prime exemplar of such an institution, but observers predict that even with the political will to do so, it could take 20 years to fully implement the accord’s 47 recommendations, many of which would be very costly.

In the meantime, UTas – like many other Australian institutions – hopes to generate finances by leveraging its existing estate as it moves to areas more accessible to locals.

In Launceston, for instance, parts of the university’s leafy campus in suburban Newnham are being sold off for housing, offices, an agricultural precinct and medical and defence facilities as university courses and services move to a budding educational and cultural quarter four kilometres away at Inveresk, a stroll from the city centre. The area also features a museum, art gallery, theatre, cafes, student accommodation, a publicly available library and a community garden, nestled between a riverside walk and Tasmania’s second-biggest football stadium.

The A$260 million campus relocation and redevelopment is the centrepiece of the Launceston City Deal jointly bankrolled by the federal government, the university, the state government and the city council. “This is the largest single infrastructure investment in Launceston’s history,” brochures proclaim. “The campus will become central to the life of the city.”

According to Black, the move was masterminded by “a coalition of people from all sectors of the city very committed to sitting around the table figuring out the best future for Launceston, with a clear vision of what that could be”.

Unfortunately, Black adds, there is “no such thing” as a clear vision in Hobart. And that, he says, is a big reason why the university’s plans to relinquish much of its existing campus there have proved, unlike in Launceston, to be so contentious.

Most of the scheme to relocate from Sandy Bay, a well-heeled riverside suburb, to a scattering of mostly heritage buildings three kilometres away in the city centre has already eventuated. Music, creative arts and media programmes have a high-tech home in the Hedberg building, which also hosts Australia’s oldest continually operating theatre. A viewing window in the floor offers glimpses of the Hobart Rivulet flowing underneath, attesting to the technical difficulties of the building’s A$110 million restoration.

A block away, the university’s long-established medical sciences precinct sits across the road from Tasmania’s major teaching hospital. Nearby administration facilities occupy a heritage biscuit factory, while a fine arts hub on the waterfront shares a restored 19th-century jam factory with a gallery and an arts supply store.

Back uptown, plans are afoot to restore the 1850 sandstone complex built for Hobart High School that operated from 1893 as the university’s first campus before space limitations forced its 1950s move to Sandy Bay, a wartime rifle range. Meanwhile, a A$131 million restoration project is converting the mid-19th-century Forestry building – which has previously served as a timber factory, emergency services headquarters and wood products showcase centre – into a new home for teaching and research, possibly in legal and business disciplines.

Across the cove from the fine arts precinct, the headquarters of the university’s Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies sits beside the Marine and Atmospheric Research division of Australia’s Science Agency, CSIRO, where the research vessel Investigator rests between voyages. Nearby, icebreakers share the dockside with cruise ships, ocean-going yachts and other pleasure craft.

“Having what is arguably the most coherent Antarctic and Southern Ocean research effort globally, sitting alongside other maritime infrastructure and the cruise ship scene – that synergy has been really powerful,” says Nicholas Farrelly, pro vice-chancellor of the university’s southern region. “You’ve got a medical science precinct that does some absolutely cutting-edge work right next to Tasmania’s most important set of hospital facilities. You’ve got a really interesting heritage precinct around Battery Point, bars along the waterfront and other parts of the city that every visitor comes to. And what do they see? They see the university there in different pockets, clearly visible without overwhelming what is ultimately civic space. It’s something that we hope everybody in Tasmania can be proud of.”

Tim Winkler, director of higher education consultancy Twig Marketing, says the idea is reminiscent of how some land grant universities in the US operate. “You can see how being involved in the very heart of Hobart could unlock some really great opportunities,” he says. “The Hobart town centre is a beautiful and historic location that attracts many, many tourists and would undoubtedly be more desirable [than Sandy Bay] for international students, for example.”

Black says push as well as pull factors have forced the move into the city. He says many of the Sandy Bay facilities are now so tattered that modernising them is not financially viable. Australia’s university sector has no dedicated public funding stream for infrastructure, let alone maintenance, and Tasmania’s high needs and low economies of scale make educational provision particularly challenging, limiting the scope to meet capital expenses via surplus internal revenue. “The way the university…has done it throughout its entire history has been, very understandably, to invest in present delivery of education and let its capital run down,” Black says. “When the university moved from the original home…to Sandy Bay, that was because the facilities [as the former Hobart High School site] were completely run down…and there was no money [to repair them]. Eventually, you hit a wall and you’ve got to start renewal.”

Reaching Sandy Bay is another problem in a state with a “very poor public transport system”, Black says. Moreover, “the jobs are in and around the centre of the city; they’re not out in Sandy Bay”. And that is an issue because most UTas students have jobs: “Very few do a full-time four-unit kind of load because people need to be paying their way,” Black explains.

But arguably the biggest push factor is sociocultural, Black says. “Large communities” of potential students have simply never been to Sandy Bay, an “elite” area so alien to the target population that some new recruits need individual attention simply to get them on to campus.

“When you’re a university wanting to say everybody is welcome, you need to be in a place where everybody is welcome,” Black says, emphasising that this view is backed up by the university’s annual survey of about 1,000 Tasmanians on why they rejected offers of places. “There are cultural barriers in Australia [that] people just do not…deal enough with when it comes to these access issues. I find it quite problematic, the degree to which we’re not ready to talk about some of those.”

The university’s move into central Hobart, however, has aroused fierce opposition from academics, students, businesses and Sandy Bay residents. In March 2022, Hobart City Council councillors demanded that the university conduct a community consultation process. In May, meanwhile, the state parliament’s upper house established a select committee to enquire into the 1992 legislation stipulating the university's constitution, functions and powers, billed as an “opportunity to constructively consider matters relating to the university’s governance and decision-making processes”. The inquiry attracted 151 submissions, many of them vitriolic, but was paused after parliament was prorogued ahead of the state election on 23 March.

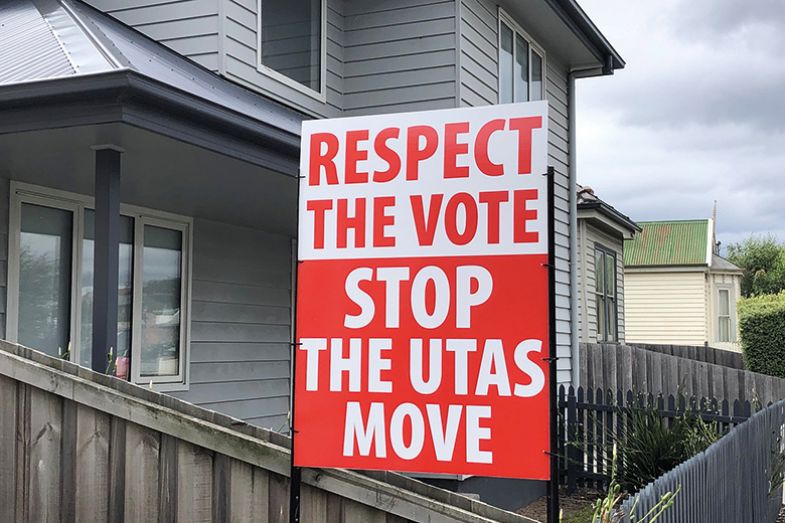

In October 2022, with relocation already well progressed, Hobart residents were quizzed on their views about the move during council elections and almost three-quarters signalled their opposition. While the plebiscite is not binding on the university or any other authority, opponents have seized on it, and placards on the windows and fences of Sandy Bay residences call on everyone to “Respect the vote – stop UTas move”.

In a 61-page submission to the select committee, lobby group Save UTAS Campus outlined its main objections. It said UTas had not provided any “substantive research” showing that largely relinquishing the Sandy Bay campus – which is slated for more than 2,000 dwellings as well as retail, offices and other developments – would boost higher education access for young Tasmanians.

The group’s co-chair Angela Bird says Sandy Bay is just 10 minutes’ drive from the central business district (known as Hobart CBD), and free buses shuttle people between the university’s Hobart sites. “There are lots of…reasons why students don’t go to university. It’s not about access or transport into Sandy Bay. Moving [the university] 10 minutes closer is not going to change this. People have been going to this university forever [and the transport situation] has never been brought up before. There’s free parking at the university. There is nowhere for anyone to park in the CBD for long periods. Where are people going to park?”

As for the concerns about Sandy Bay’s off-putting elitism, these are “ridiculous”, Bird says. “I came from the other end of the state in [northern port city] Devonport and I did not even consider the status of the suburb as an issue.”

The group also questions the university’s assertions about the environmental sustainability of a move that potentially involves demolishing buildings and destroying parkland. And Bird questions claims that the move will stimulate small city businesses. “Inner-city business [operators] believe [the area] would be much better used for housing, retail and offices,” she says. “Students are only there for 24 weeks a year. They don’t have much disposable income anyway. Permanent residents in inner-city apartments have a lot of disposable income and are there 52 weeks a year. The coffee shops around the current [student] accommodation in the CBD say that their customers are not students: they’re city workers.”

Save UTAS Campus says the university’s statements about stimulating local economies suggest it has lost sight of its primary educational mission. But Black says social and economic stimulus is part of the primary educational mission.

“We don’t do a good job…unless we are very attentive to ensuring that the nurses [we educate] have the skills that Tasmanian health needs; that people we’re educating for businesses have the skills Tasmanian businesses need. These [arguments are] often framed as a kind of simplistic either-or. Higher education today is absolutely about the ability to do both.”

As the island’s sole university, UTas has been able to strike some unique arrangements with key public sector employers. Police recruits undertake the bulk of a bachelor’s degree as part of their mandatory training under a longstanding agreement between Tasmania Police and the university. “Tasmania has the most educated police force in the country, and outcomes to match,” Black says.

The nursing simulation suite at the new Burnie campus recently produced its first cohort of graduates, largely local recruits now filling local jobs in Tasmania’s notoriously underserviced north-west.

Meanwhile, the university’s building spree has given impetus to fledgling local industries. Determined to line Hobart’s refurbished, glass-domed Forestry building with an alternative to high-carbon plasterboard, for instance, the university chose hempcrete, a material made from lime, hemp and water. It undertook fire testing certification for a local hemp business, helping to drive its commercial expansion. And the Inveresk project at Launceston featured extensive use of cross-laminated timber, helping to generate a new product line for a struggling local sawmilling industry previously dedicated to woodchips. “We…aim to be a positive force for building industry capability,” Black says.

Yet the Hobart move is only one reason why Black (above) is one of the most embattled vice-chancellors in Australia. He is also criticised for perceived failings common to most Australian university leaders – heavy-handedness, standoffishness, unwillingness to genuinely consult and inability to rein in pervasive bullying, job insecurity and underpayment of casual staff.

Union branch president Beckett says vice-chancellors are paid “big bucks” to solve difficult problems but often fall short and move on. “They use terms [like] good faith, but there’s not a lot of good faith,” he says. “These people are put into these positions with all this expertise, seven-figure salaries, but...but we never ever see [changes] through and into operation. New change comes on top, or someone else comes in and says, ‘I’ve got another way of doing it’. We’ve often said, ‘We just reinvented the wheel’ because we’ve come a full 360 and we’re back where we started.”

But staff demographics offer an implicit endorsement of UTas, which is proving a magnet for young recruits – unlike most Australian universities, where the staff profile is getting older. UTas says its proportion of academics aged over 55 has declined in recent years, while younger academics have become more numerous – particularly 25-34-year-olds, whose share of positions has increased by 35 per cent.

University of South Australia human resources professor Carol Kulik says this partly reflects Tasmania’s image as an outdoorsy place with low crime rates. “People are very attracted to living in Tasmania when they have young families,” she notes.

But Black says the university also deserves credit. “People are keen to join us. [They] want to be part of this mission. It’s quite a big thing to move to Tasmania: that’s a big life commitment.”

And that mission remains primarily local, even as the university, like all Australian universities, does what it can to recruit international students to fill funding gaps. The arrangements with intermediaries that less well-known universities have to enter into present their own sets of ethical challenges, of course, and UTas was mentioned in a 2019 Australian Broadcasting Corporation exposé of unethical international student recruitment. Yet while the main subject of the broadcast, Perth’s Murdoch University, endured a regulatory and reputational battering until its public image was rehabilitated under new leadership, UTas won plaudits for its handling of the situation, hiring governance expert Hilary Winchester to investigate the allegations and accepting her 19 recommendations.

“They said, ‘We think we’ve got a problem here; let’s get someone to really have a good look and see how we can improve,’” Winchester says. “That’s the way to go, rather than saying ‘nothing to see here’. I think that put them in good standing.”

However, UTas’ handling of the Hobart move remains contentious despite its having published its masterplan and consulted residents on it. So much so, in fact, that Tasmania’s governing Liberal Party promised to introduce legislation prohibiting the sale of the Sandy Bay land without “the explicit support of both Houses of the Parliament” if it won a clear majority in the 23 March state election. While votes were still being counted after THE went to press, the party had little prospect of winning a majority of seats.

Marketing consultant Winkler says UTas’ “tourist brochure” approach to promoting its attributes is inadequate. “You have to tell a true story, but also you have to tell the story well. That means being engaging and understanding where your pain points are. It’s like a political campaign. It’s not what we say: it’s what everybody else says about us. If you’ve only got a couple of people in the community speaking up for you, then you need to look at why.”

For his part, Black is still of the view that the lack of a wider agreed city plan for Hobart is part of the reason for the volume of contention: “If you don’t know what the future is, then you don’t want to lose what’s been good about the past,” he says. However, “we know that’s not a good recipe for the future of cities – to be nostalgic about the past when the world has changed”.

In the absence of a wider plan, Black says that the university has, in some senses, “become the plan”, resulting in its attracting “all the attention [for] a whole bunch of issues which need to be part of a bigger plan, [such as] parking and transport”.

It is also fair to say that while Tasmania’s climate may be the country’s most temperate, its current affairs are a different story. Tasmanians seem to love a good stoush, with the university’s move far from the only bone of popular contention. Other proposals draw no shortage of impassioned advocates on both sides and surprisingly few fence-sitters. Examples include a wind farm in remote Robbin Island; an aquaculture facility in Storm Bay near Hobart; a cable car up Hobart’s mountain backdrop; and a football stadium on the waterfront.

And as well as flak, UTas can draw fierce proprietary protectiveness from ordinary Tasmanians, including many that have never attended it. And the contention all speaks to the importance of regional institutions such as UTas to their local populations, as recognised in the Universities Accord, with many individuals feeling they have much more to gain or lose from “their” university’s decisions than big-city dwellers do.

“It’s a unique relationship,” Black concedes. “And as with any close relationship, it has challenges.”