Persuading politicians and officials to ingest the fruits of new research and then to regurgitate them in the form of sensible policy is a frustrating process at the best of times. Policymaking is intangible, diffuse and shapeshifting. One result is that too little research with lessons for policymakers hits the target.

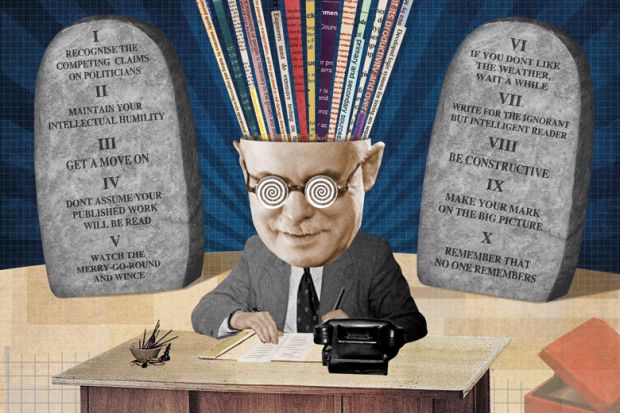

The government has recently performed a U‑turn on a policy that could have banned publicly funded academic researchers from campaigning for changes to the law. So this is a good moment to consider how to manage academics’ expectations while ensuring that their research has the biggest possible impact. Bearing in mind these 10 commandments – based on my own experience of policymaking – will help.

1) Recognise the competing claims on politicians

Most politicians and civil servants are in it for the right reasons. Of course, a few are not, and many are resistant to evidence on one or two high-profile issues – think, for example, of the support some MPs give to homeopathy. But, in general, Whitehall and Westminster are receptive to interesting new evidence. The challenge for academics is that, in a democracy, it is policymakers’ absolute duty to take a full range of factors into account. For the politicians, if not the civil servants, that includes what voters think – which may not immediately accord with the latest research. As one defeated US politician once exasperatedly said: “The people have spoken, the bastards.”

2) Maintain your intellectual humility

Another reason that policymakers are not mere automatons implementing whatever researchers tell them is that evidence is contested. For example, when universities control for the prior achievement of applicants, some say it is school type – comprehensive, grammar or independent – that matters. Others say that it is a school’s overall performance, as not every comprehensive is Grange Hill and not every independent school is Eton. Similarly, the evidence on whether having more male school teachers could tackle the underachievement of boys is as clear as mud. Some of it suggests that more men would help; the rest does not. Policymakers cannot just follow the evidence when it points in opposite directions.

3) Get a move on

Another frustration with some academic research is the time it takes. Of course, good research can be published only when it is ready; the important recent research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies that highlighted the key role of social background in determining earnings levels even among graduates of the very same university programme took the length of the First World War to complete. If there is a chance of your research hitting the zeitgeist, do not wait until people have lost interest before you get in touch with policymakers. Initial conclusions can be flagged, published or just discussed face to face. Contrary to the caricature, policymakers do not generally work from the back of a fag packet, but neither do they need every figure to be calculated to the 15th decimal place.

4) Don’t assume your published work will be read

Policymakers have no access to academic journals. There is no institutional Westminster or Whitehall log-in, so politicians and civil servants generally see less academic research than the greenest undergraduate. When I was a civil servant, my department would go into meltdown if I asked to see an academic paper, as there was no budget for the $30 cost of accessing it online. This is the reason the Higher Education Policy Institute controversially recommended a national licence to enable anyone with a computer in the UK to access previously published research. It is also a key reason why MPs recruit student interns: they bring their log-in details with them.

5) Watch the merry-go-round and wince

The problems in getting research taken seriously in Whitehall are typically not so much to do with the calibre of policymakers but the way that government operates. Civil servants have to change jobs frequently if they want to be promoted, hindering the accumulation of true expertise. In my three and a half years as a special adviser in the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, our ministers had five sets of private secretaries and the department had three different permanent secretaries. The velocity at which officials circulate has been accelerated by endless departmental reorganisations, encouraged by austerity. The impending closure of BIS’ Sheffield office and the loss of expertise that will entail will make matters even worse for higher education.

6) If you don’t like the weather, wait a while

The one advantage of the rapid turnover for those wanting to have an impact on policy is that when you reach a dead end with one official, you just have to wait for the next one to come along to have another go at removing the blockage. Sometimes policy initiatives that have been non-starters for years can be taken up overnight. I fought hard for universities’ Key Information Sets to be available in an accessible form on mobile phones, but was repeatedly told that it was technically too hard and expensive. A year later, I discovered that the problem had been cracked and my suggestion was about to be implemented. It is the same across the world. A few years ago, the US stopped funding its citizens to study at UK institutions without degree-awarding powers. Specialist institutions, such as conservatoires, were hit hard. Initially, no one in Washington would help out but, a few months later, the problem vanished after some changes in personnel.

7) Write for the ignorant but intelligent reader

New political incumbents must get up to speed quickly but may not know much yet. If you capture them, you capture others. But a good argument must be presented well. Aristotle said that rhetoric has three elements: logos – the argument itself; ethos – the credibility of the speaker; and pathos – the appeal to emotions. Too many potentially influential academic papers fall on stony ground because the language is inaccessible, the data are not explained intuitively and it is unclear how policymakers are meant to respond. Indeed, academic norms value opacity over clarity so much that doctorates generally have to be rewritten before they can become published monographs.

8) Be constructive

The higher education sector is better at destructive than constructive criticism. This is a problem. Far too many academic papers that could have an impact on policy (including the IFS one on graduate earnings) include brilliant analyses followed by weak policy conclusions that read as if they have been added at the last moment. Yet if the people conducting a particular piece of research cannot work out its consequences for policy, it is unlikely that others will be able to either. It is also not enough to assume that an optimistic cost-benefit analysis will win the day. Showing that spending £1 now will save hundreds of pounds at some future point resonates only if the underlying calculation is very rigorous and compares well with those put forward by people across all other areas of policymaking.

9) Make your mark on the big picture

Modern politicians and governments work from overarching narratives, so policy prescriptions are more likely to be taken up in the short term if they fit with those. When he was minister for universities and science, David Willetts corralled the research community’s huge lists of funding priorities into “eight great technologies” as a way of persuading the Treasury to increase funding. There were two reactions from researchers who feared their subdiscipline had been omitted. Some shouted loudly that the categories were political inventions and that the whole concept was flawed. A smarter response came from those who wrote in saying that they just wanted to double-check that their area of expertise was included. They posed the question in a way that expected – and received – a positive answer.

10) Remember that no one remembers

There is no history in Whitehall. That does not particularly matter when it comes to the Celts or the Tudors, but it is more debilitating as regards the recent past. When the policy to triple tuition fees was being drawn up in 2010, there was barely anyone around who had worked on Tony Blair’s tripling of fees just a few years beforehand. As a result, ministers falsely – but sincerely – claimed that fees at the ceiling £9,000 level would be exceptional, rather than the norm. Within the department, we did not initially even know the precise legal powers of the Office for Fair Access, nor the parliamentary procedure for tripling fees. As an amateur historian, this ignorance of the past frustrated me so much that I spent my free time penning a piece on the history of student loans in the UK between 1962 and 2012. This was immediately rejected from the first journal I sent it to, without being sent out for peer review, on the grounds that the story was “familiar to those of us who teach the history of higher education policy in this period”. That begs an important question: if it was so familiar to them, why had they failed to tell those of us setting policy?

Nick Hillman is director of the Higher Education Policy Institute. He was previously special adviser to David Willetts, the former minister for universities and science.

后记

Print headline: 10 commandments for scholars seeking to sway policymakers