“Love is the infinite placed within the reach of poodles,” wrote the French novelist Louis-Ferdinand Céline, archly cynical, in his 1936 novel Journey to the End of the Night. But when the contemporary French novelist Philippe Sollers reminds his wife, the Bulgarian-born philosopher Julia Kristeva, of Céline’s scathing enunciation, it is with a charming glee. All their exchanges in this co-authored collection have the warm, good-humoured glow of a shared sensibility, the assured confidence of a coupling that has been long, supportive and sustaining.

Coupling, or at least that rather blank designation “the couple”, is a term for which Sollers doesn’t much care. But searching for a language that could be precise enough to seize the fact of love, capable of capturing its different dynamics and disturbances, is the business of this assortment of interviews, exchanges and ruminations. In Marriage as a Fine Art, Kristeva and Sollers seek to examine their relationship at arm’s length, despite having had those same arms hopelessly wrapped around each other since 1967. They are at pains from the outset to distinguish the terms of their project, lest it be mistaken for a memoir (quelle horreur!), floppy with sentiment and sagging with self-regard, or a desiccated philosophical broadside on the institution of marriage (quel ennui, perhaps).

The truth is that their loyal readers probably wouldn’t mind either, trusting that anything with Kristeva and Sollers at the tiller is sure to be steered somewhere illuminating and enlivening. As it stands, the collection is evidently an only loosely organised assemblage of introductions, interviews and talks. Happily, though, the book is littered throughout with the debris of their insight and intelligence. And there is a kind of modesty to the haphazardness of this gathered material because it also signals their refusal to totalise or universalise from their own particular experience. “We shall rather try to tell all about a given passion with precision,” Sollers pledges. The merit of the book is this dedication to delineating experience acutely.

Kristeva and Sollers duly lend their attention to the various tensions and traits of a marriage – fidelity, secrecy, narcissism, passion – musing out loud, trading observations and interpolations. It is a mark of the agility of their analysis that they manage to cast light upon a certain idea, dilemma or disposition without always baring the details of their own particular experience of it. Here, the book manages a peculiarly simultaneous candour and caginess, most apparent in a 1996 interview with François Armanet and Sylvie Véran for Le Nouvel Observateur in which Kristeva and Sollers dismantle the idea of fidelity. They casually toy with the thesis that fidelity might be “a hangover from the past”, only “a quaint relic”. When the uncomfortably sandwiched interviewers take their lives into their own hands and bravely enquire whether the “affairs you both went in for” were a precondition of marriage or the breaking of a pledge, Kristeva answers unperturbed, as tranquil as a leaf on a breezeless summer’s day: “We never made that pledge.” It’s a deliciously awkward moment, and a reminder to philosophy’s scholarly sobersides of the mischief lodged deep in French thought (and French thinkers).

But it is also the dynamism of this kind of thought that enables Kristeva and Sollers to understand marriage as an “art”, rather than an institution. Theirs is a marriage that has endured with “an uncompromising vitality”, as Kristeva writes, “because it never obeyed any law but its own”. It is, instead, she explains carefully, “a permanent adjustment, running and lucid, nurtured by two reciprocal and distinct freedoms”. This is an idea at once radical and perfectly sensible: marriage is fluent, not fixed by a ring. It is constituted by the constant recalibrations of the very relationship it seeks to contain.

This is a conception of marriage clearly indebted to a particular branch of continental philosophy of which Kristeva herself has been such a powerful proponent and whose principal tenet is an idea of selfhood that is never shored up, being instead always modified by its relationship to an other. What’s so remarkable (and moving) here is her quiet attestation that marriage should not be unmoored by this, but made more powerful still “since it is founded not upon objective law, but conviction”. And if conviction feels somehow more human and kindly than law, it is also more vulnerable, a strangely uncharted thing, subject to the vagaries of temper or tiredness. Perhaps this is Kristeva’s point. There is jeopardy in marriage, a certain precariousness at the heart of any act of union that challenges us to vigilance.

Sollers and Kristeva are such patient, natural and considered expositors of this philosophy because they live it as well as think it. It is the vigour of philosophical ideas understood in a living process that gives this book its excitement. There is a passionate intensity in the ways that they engage with ideas and each other – although passion itself gets rather short shrift when Kristeva seizes it by the scruff of the neck and gives it a severe talking-to: “Passion does what it wants, for good or ill…Amorous passion as inescapably leading to sacrifice and death. It’s a highly structured ideology and still hugely powerful today.”

The counter to ideology, of course, is critique, but the book is wisely averse to didactic pronouncements (or even marriage guidance), preferring instead riffs and parries, a relay of questions posed and answers modified. And it’s in these rallies back and forth that Kristeva and Sollers also betray their faultiness, the briefest glimpses of vanity and self-vindication. Early on, Sollers, intriguingly, articulates an antipathy to transparency, averring: “I’m all for secrecy.” He rejects the compact apparently made between Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, the agreement by each to share with the other the details of one’s conquests. It’s a curious moment for Kristeva and Sollers, implicitly registering their likeness to their predecessors and acknowledging the fascination with which their private lives might be regarded as fair philosophical game.

But later in the collection, Kristeva herself suggests that there can be no secrecy, since “one always knows, definitely”. This is the psychoanalyst speaking, supremely confident both of the fact of the unconscious and the skill of the analyst for whom the psyche is an open book if only they care to read it.

Sometimes, though, there is something alarmingly brusque in this Kristeva. She dismisses the feeling of betrayal as a mark of “zero-confidence”, the symptom of an over-sensitive, “battered” narcissism. Later, she breezily concedes, “I don’t like other women enough to be jealous of them. It may be my problem, but still, what a relief!” It is, in itself, a rather unlikeable statement, but more telling perhaps is how unpersuasive it is, as though it were ever possible to be indemnified from pain or possess a self unperforated by others.

But this is a fascinating book precisely for these follies, as well as for its myriad insights. Towards the end of the collection, Kristeva recalls the French novelist Colette’s distaste for love. “That uninflected word”, she wrote, “is not enough for me.” Certainly, the word is not enough. The thought of love, though, is another question.

Shahidha Bari is lecturer in Romanticism at Queen Mary University of London.

Marriage as a Fine Art

By Julia Kristeva and Philippe Sollers

Translated by Lorna Scott Fox

Columbia University Press, 128pp, £19.00

ISBN 9780231180108 and 1543033 (e-book)

Published 20 December 2016

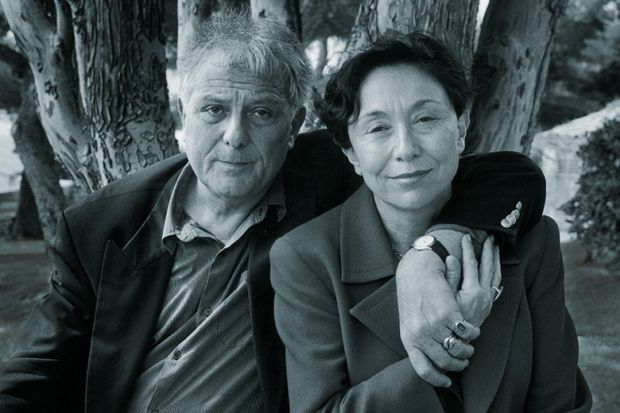

The authors

Writer, psychoanalyst and academic Julia Kristeva was born and raised in Bulgaria. Asked about its influence on her, she points to the annual “Day of the Alphabet” – the 24 May celebration known as Bulgarian Education and Culture and Slavonic Literature Day, held on the feast day of the inventors of the Cyrillic alphabet, the saints Cyril and Methodius.

“Once a year, I would wear a large letter of the Bulgarian alphabet pinned to my blouse,” she recalls. “I became A LETTER, like all schoolchildren, university students, those working in the cultural professions…Bulgaria is the only country in the world, I believe, that celebrates a national day of culture.”

If Kristeva could change one thing about Paris Diderot University – Paris 7, where she is professor emeritus, it would be “that the teaching of French and comparative literature would be added to the courses of all students in the sciences as well as in law and social sciences. At least two years of courses and obligatory seminars, and in all the other years, optional courses.”

Asked to recommend a recent work by a young academic that she found impressive, she names Hébreu, du sacré au maternel, the doctoral thesis of Keren Mock Gitai, which Kristeva supervised, on maternal language and writing.

How does Kristeva spend her wedding anniversaries? “There is no need for a special celebration,” she replies, “as we renew our vows every day and night.” As to what gives her hope, she says it is “the certainty that as part of a couple, being reborn is never beyond my abilities”.

Her husband, the critic, Sinophile and writer Philippe Sollers, is a native of Bordeaux, which he does not hesitate to proclaim “the most civilised city in the world”, marked with “the taste of wine, a permanent Dionysiac presence, and the ‘colonne des Girondins’, the monument to the Girondins, the most inspiring political faction in the French Revolution”.

If he were ever obliged to leave Paris, or France, where would he go? “I regularly leave Paris to live in Venice,” he notes. “And if Paris were to become suffocating, I would pitch up at the Île de Ré, just opposite the bell tower in Ars, a fabulous ancestral location that I intend to leave in my will to the Chinese students of the future who love my novels.”

Sollers is known for his admiration of the work of James Joyce. But asked which American or British novelist peer of today he most admires, he replies, “Not too many of them – or, alternatively, Philip Roth! In any case, he’s a friend.”

Does he remember what he wore on his wedding day, and the best part of the occasion? “I was dressed just as I did every day,” he says. “My wife and I went to dine with some friends on the banks of the Seine.”

Of all the awards he has won for his writing, which would he say was the most significant or brought him the most delight? Le Prix Montaigne, of which he was the inaugural winner in 2003 – and which brought with it 120 bottles of Bordeaux.

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: A couple bound by conviction, not convention