Marco Santagata is a distinguished literary scholar at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa and a prizewinning creative writer. The original Italian subtitle of his new biography of Dante – Il romanzo della sua vita (The novel of his life) – suggests that in writing it he might be drawing on his creative talents as well as his academic expertise. Dante is a writer about whom documentary evidence is notoriously scant; his works, although deeply rooted in his lived experience, for the most part resist analysis in narrowly biographical terms. About the key episode in his life, his banishment from Florence and the death sentence that went with it, the only document that survives is the death sentence itself, preserved in the Florentine state archive. Dante never wrote about it or the events that led up to it, although his masterpiece, the Divine Comedy, is inconceivable without it. It is the traumatic event on which his whole life turns, and around which his poem is structured, and yet we know almost nothing about it.

T. S. Eliot famously made a distinction between “the man who suffers and the mind which creates”. Benedetto Croce elevated a similar distinction to an aesthetic principle when he insisted that a writer’s personalità pratica and his personalità poetica (the flesh-and-blood human being who lived the life and the artist whose intellectual and emotional experiences and energies fashioned the work) are two very different things. To reconstruct the life from the work will always be a delicate operation, and never more so than with a writer where we can demonstrate (as Santagata ably does) that the ordering and shaping imperative often trumped a historian’s concern with factual truth. Undeterred by any such theoretical misgivings – indeed (one suspects) relishing the challenges that his subject presents, and never fudging the difficulties and complexities of the relationship between life and art – Santagata has written a book that any reader interested in Dante will find absorbing, richly informative and very thought-provoking.

The book, like the life, falls naturally into two not-quite-equal halves, pre-exile and post-exile. A bulky section of immensely detailed endnotes follows the main narrative: testimony to Santagata’s command both of the documentary evidence and the long tradition of scholarly engagement with it, although some lengthy notes running to several pages have been shoehorned in where they have no obvious connection at all with the narrative. The decision to corral the notes at the end of the book was a wise one. Reading them in tandem with the main text (as a reviewer must) impedes the narrative flow, losing the impetus of the author’s notably lively, informal and engaging style. In the main text, Santagata’s narrative and organisational skills guarantee that complex historical information is introduced seamlessly into the story and brought vividly to life.

The first section (“Florence”) traces Dante’s family circumstances, his emergence as an accomplished writer of love poems, and his involvement in the turbulent world of communal politics in the city from the mid-1290s on. Especially interesting is the picture that emerges of his straitened economic circumstances. The dry documents of the Codice diplomatico dantesco, which record details of loans made to Dante and his half-brother Francesco, or indeed made by Francesco to Dante just weeks before he took on the role of prior, at the apex of his political career, take on new life as Santagata ponders the circumstances and implications of these transactions. The families of both Dante’s wife Gemma Donati and his beloved Beatrice Portinari and her husband were vastly superior in social status to his own. A bride’s dowry was determined by the groom’s economic status, not her family’s: Gemma’s modest 12 gold florins stand in telling contrast to Dante’s sister Tana’s 366 gold florins. (Both were prestigious marriages for the Alighieri family.) Concrete details of this kind anchor this part of the story in documented facts. Dante’s lifelong obsession with the subject of true nobility and how it is to be understood is plausibly linked to his insecure social and economic status. So, too, is his sense of his own exceptionality, the single characteristic Santagata picks out as defining his personality from the very beginning.

When the source for reconstructing the life is not a document but a literary text, the situation becomes problematic. In the Vita nova, Dante describes his hyper-sensitive psychophysical reaction to certain events. Santagata is inclined to believe that he was epileptic, a view advanced in the late 19th century by Cesare Lombroso, who linked the condition with the pathology of genius (a view from which Santagata carefully distances himself). In general, Santagata proceeds with due caution. A typical short paragraph includes the phrases: “It would seem…It is reasonable to suppose…It is possible…It would have been difficult…”. So scrupulous is he in distinguishing between conjecture and certainty that the reader is pulled up short by the occasional slippage from cautious rumination to bald assertion of unsubstantiated fact, as when we are told that Dante must have followed the imperial court to Pisa in early March 1312, and that in Pisa he devoted himself to writing his political treatise, Monarchia. But we simply do not know these things to be true. (We need to consult the notes to find that opinion is divided on the matter: “Dating Dante’s works can be a hopeless task, and Monarchia is no exception” – a good example of the sometimes uneasy relationship between narrative and notes.)

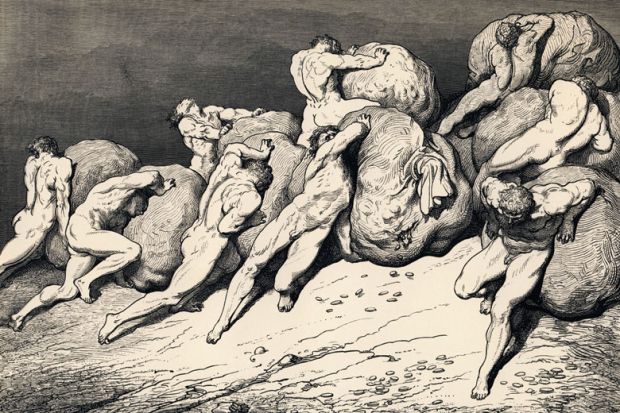

The second half of the book (“Exile”) gives an illuminating account of the social and political realities of those regions of Italy that Dante visited during his years of exile, with emphasis on the importance for his evolving political thinking of the Casentino and the Lunigiana, and the great feudal dynasties of the Guidi and the Malaspina (for whom no fewer than eight family trees are helpfully provided). It is in this second half of the book that the problem of the relationship between life and art becomes critical, since we know so little (in effect, nothing at all) about the composition of the Commedia.

On three separate occasions Santagata describes the Commedia as an “instant book” – a curious phrase for a work written over a period of 15 years (or longer, if we accept his own view that the nucleus of the poem pre-dated the exile). The paradoxical phrase underscores his approach: the poem is mined to throw light on the changing political realities with which Dante was dealing in the years of his exile, and the complexity of his shifting political allegiances. Conversely, the historical realities, to the extent that they can be reconstructed, give clues to the chronology of the writing (or rewriting, or reframing) of different parts of the poem.

This approach gives a strong sense of Dante as an intellectual and political animal, but little sense of the creative writer and poet. The poetry is seen simply as an instrument for furthering his practical political aims, for negotiating the difficulties of his immediate real-life circumstances. Even the treatment of episodes in the poem that are directly political (Farinata, Brunetto) seems perfunctory: the complexities and nuances of a literary and poetic text are unacknowledged. Of Dante’s astonishing linguistic skills, of the expressive power and fierce originality and poetic force of the language of the Commedia, we hear nothing at all. Perhaps Santagata counts on his Italian audience taking this for granted (in Italy, the book has its own fan page on Facebook). English readers must take the imaginative power and linguistic brilliance of the Commedia on trust; but with their well-known fondness for literary biography, they will surely be grateful for this bold, vigorous and invigorating account of Dante’s life and times.

Prue Shaw is emeritus reader in Italian studies, University College London, and author of Reading Dante: From Here to Eternity (2014).

Dante: The Story of his Life

By Marco Santagata

Translated by Richard Dixon

Harvard University Press, 496pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780674504868

Published 28 April 2016

The author

Marco Santagata, acclaimed novelist and professor of Italian literature at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, was born in Zocca in Emilia-Romana.

Marco Santagata, acclaimed novelist and professor of Italian literature at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, was born in Zocca in Emilia-Romana.

“In a small place where everyone knows each other, lasting friendships are often formed during childhood and early youth, and it happened to me with my friends from Zocca. We live in cities far apart, we have quite different careers, but even so many years later we feel a sense of community. It’s a feeling that gives security, and I believe that it’s this factor, more than any other, that helped develop in me an optimistic view of life.”

Zocca, he adds, is “a small Appenine town that has been largely bypassed by history: there are no great churches, castles or notable monuments. The scenery is pleasant, but nothing like the beauty of the Alps. Nevertheless, it is a well-known town in Italy, because it’s the birthplace of Vasco Rossi, absolutely the most famous rock star in the country. Fans make pilgrimages to Zocca year-round. But Vasco is only the best-known name among a noteworthy group of people, all born in Zocca, who have achieved lofty positions in their professional worlds: writers, politicians, journalists, psychiatrists and even the first Italian astronaut.

“It’s a phenomenon that has drawn a lot of comment: how can a town of fewer than 5,000 inhabitants have produced, in a single generation born between the end of the 1940s and the 1950s, so many noteworthy figures? Nobody has the answer, really, but it’s a clear sign of how regional Italy can be a fertile terrain for giving rise to new energies. This, I realise, is not sufficient reason to draw people to visit Zocca, and so I’d just note some other attractions: Zocca, like the whole region, is a gastronomic centre of notable excellence; the Modena region it’s situated in is rich in great works of art, and it’s worth remembering that T.S. Eliot argued that the Romanesque cathedral of Modena is the most beautiful church in the world.”

Were you a studious child, and did your parents, your teachers or other adults influence your love of reading, literature and thinking?

“My father taught literature at secondary school, and my mother was an elementary school teacher. There was a large collection of books at our house. I learned to read and write on my own, before going to school, just flipping through the books at home. So reading has been a part of my life since I was very small. My father’s example led me to pursue literature. He was a graduate of the University of Bologna, where he wrote his thesis on Castelvetro’s commentary on Petrarch’s Canzoniere. It was no coincidence that, before devoting myself to Dante, I spent many years myself studying the Canzoniere.”

Asked how old he was when he first read Dante, and what he thought of the poet’s work, Santagata replies, “I would have first read Dante’s poetry when I was in middle school (aged 11 to 13), but I don’t remember when and if it really struck me. I do, however, remember that in my early adolescence, what really inspired me was the poetry of Giacomo Leopardi and those of Paul Verlaine, from what I could manage to read of them in French. Dante requires a maturity that I didn’t yet have.”

Dante’s poetry is as important to Italian culture as Shakespeare is to anglophone culture, and many of his words are part of common speech in everyday Italian conversation. Has Santagata a favourite line of Dante that every Italian knows and uses?

“Gianfranco Contini, a great critic and scholar who is less well known abroad than he deserves, has written that among ordinary people, Dante’s influence is ‘centonaria’, in other words, rather than episodes or stories from his work, what remains in the common memory is single verses. And in fact it’s normal that in everyday conversation, people use – sometimes without even knowing that they are doing so – expressions such as ‘in the middle of the journey of our life’, ‘do not speak of them’, ‘I fell as a dead body falls’, ‘the pain of hunger was greater than my grief’, ‘and we came forth to see the stars once again’, and many, many others.

“This also takes into account the fact that at least up to the generation of my grandparents, let’s say up until the end of the first decades of the 20th century, many working-class people who were illiterate or nearly so knew entire cantos of Dante by heart. I remember that my paternal great-grandfather, who was a carter by trade, recited from memory the entire Gerusalemme liberata of Torquato Tasso and Dante’s Inferno. Today, one of the great vehicles for dissemination of the phrases and verses of Dante is advertising. But for myself, I confess that there isn’t a single verse of Dante that springs to mind more than another. Verses of Petrarch spring to my mind much more easily than those of Dante, although naturally this doesn’t imply any value judgement with respect to the literary merits of the two.”

Of his undergraduate days, Santagata says: “I studied at the Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa, which was and is the most prestigious university in Italy. Entrance is via challenging and selective application process: when I was accepted, in 1966, there were only eight places available for a field of candidates, if I recall correctly, of around 400. Normalisti of the past and of today are strongly competitive and equally strongly determined. I believe I was no exception, and I adjusted to the spirit of the institution.”

Santagata has held posts at universities in Paris, Geneva and Mexico City. Did he find the academic culture there markedly different to that in the Italian academy?

“Until about 20 or 25 years ago, there were still notable differences between the cultural climate, and especially the didactic practices, of Italian universities and those that I experienced at the foreign universities I happened to teach at. The notion of an elite university still prevailed in Italy, which was not accompanied by the same degree of care paid to teaching, and the same attention to relations with students, that would be found in, for example, France and Switzerland. Today, it seems to me, that at least in Europe, the university system has become much more homologous, or tending toward it.”

If Santagata could discover one thing about Dante that is not known – a fact about his life, for example – what would it be?

“We know so little of Dante’s life that each new discovery would be precious. The dream of all Dante scholars would be to find at least a handwritten signature. This would allow us to recognise the hand of Dante in certain manuscripts that have been handed down as his works. Personally, I would be content with even less. It would be enough for me to find a document that attests to the presence of Dante in Pisa at the court of Henry VII. It would prove my hypothesis that Dante lived in that city, and that it was there that he wrote the Monarchia.”

Santagata’s novel Come Donna Inamorata is a work of fiction about Dante. What did the fictional form allow him to do that the scholarly non-fiction form does not? And does he see it as a brave or dangerous decision for a Dante scholar to write fiction about him?

“Taking Dante as the protagonist of a novel is definitely an almost foolhardy decision. The risk is of falling into involuntary parody or to subject the subject to stereotyped images of him that have been circulating for centuries. Why did I do it? Essentially because a book of fiction allows me to push beyond the boundaries that necessarily constrain even the most daring forms of literary criticism. For some time I have been interested in exploring the elusive zone in which germinate the ideas that then become creative works; we could also call it the ‘quid’, that thing that we used to call inspiration that lies between biography and literature. An area that the instruments of criticism, with its protocols and exigencies of verification, do not permit you to enter. Fiction, fantasy, which doesn’t arise from a documentary base, can allow you to go with hypotheses and inventions to say something that you otherwise could not: invented things, yes, but things that can also open up new avenues for understanding the work of a writer.”

He adds: “The intention was to show Dante as man among men, or, if you prefer, to get him down off the plinth. To show an uncertain Dante – contradictory, ambitious and even cowardly at times – does not mean to demolish a myth, but rather to scrape away the many accretions of myth that he has acquired over the centuries.”

In a recent much-noted article in Corriere della Sera, Santagata is said to have suggested that Elena Ferrante – the pseudonymous and acclaimed author of the Neapolitan novels that include My Brilliant Friend – is the academic Marcella Marmo. Why did he try to determine the identity of an author who does not wish to be identified?

“Let me clarify: I did not write that Marcella Marmo is Elena Ferrante; I wrote that Marcella Marmo corresponds to an identity that could be assembled from some sections of My Brilliant Friend. In other words, that behind one part of this story you can read of life experiences that are relatable to Marcella Maro. Which does not exclude the possibility that behind other parts of the books, you can read of experiences that would correspond to other historical persons. This could signify that that the self-styled Elena Ferrante is not one person, or at the very least, is a person who has drawn on the collaborations of others. But this is just my unsubstantiated impression. Why try to uncover who she (or he) is? My reply is that if, as a philologist, I strive to identify the author of Il Fiore or the Epistola XIII a Cangrande della Scala [both attributed to Dante], why should I not try to do the same for a contemporary book? I do not believe that contemporaneity implies a difference in status.”

What gives him hope?

“We inhabit a historical contingency that impedes the nourishment of many hopes. The hope is that this is indeed just a contingency. The fear is that the shadows of a past that was not so very long ago are presently growing ever thicker around us.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: The devil is in the details