This American Life is a long-running radio show (now podcast) produced in Chicago. Each week the producers choose a theme and tell various stories around it. One of my favourite episodes considers the seven conversational topics that are so boring they kill any hope of animated discussion.

These conversational rules come from the English mother of one of the producers, a highly unofficial source. The boring topics she insists should be avoided are: your health (unless you’re speaking to a close friend); your diet (including the carbs/soy products/lactose/sugar you’re not eating); how you slept; what you dreamed about; anything about your period; money; and route talk (for example, how you drove from Carlisle to Moffat without getting on the A74).

As the holidays approach, we’re all at risk of finding ourselves in soporific chat on these topics. But they don’t have to be so boring. Simply by taking inspiration from medieval history, you can inject life into otherwise flatlining conversations. These specific topics can become utterly fascinating by sticking the word “medieval” in front of them and turning them from first-person into third-person narratives. When done properly, the formula becomes a veritable cocktail party and dissertation topic generator.

Here are some examples for turning ho-hum chit-chat into thrilling discussions.

Health: To those who complain that their wait at the doctor’s clinic or hospital was long, remind them that at least they weren’t waiting to be bled. The health regimen of a thirteenth-century nun, along with all her sisters, included being bled twice a year by a trained surgeon. Or, your conversants could be thankful they weren’t earning their living as a medieval painter, who was constantly exposed to lead whenever he or she used white paint. We know now that even small amounts of exposure will lower children’s IQs. How did this medieval exposure affect painters’ cognitive abilities, quality of life, and life expectancy?

Diet: Questions to bring up when faced with a snoozy explanation of why someone is avoiding carbs: do you ever wonder what Marco Polo’s diet was like? Or what foods he encountered as he left Italy and travelled east? Which items did he bring back? How did perishability affect transportation?

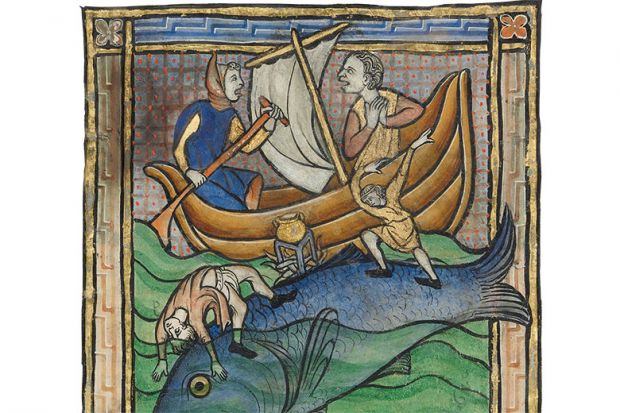

Sleep: To someone complaining about poor sleep, bring up how medieval urban dwellers slept: with bedbugs! In the Hortus Sanitatis, which existed in manuscript form before it was printed in editions from 1485 and 1491, there is a long discourse on the nocturnal bloodsuckers. How did medieval sleepers itch and swell and fester through the night? (I owe this image and reference to Beth Morrison).

Dreams: Are dreams all they used to be? They play a major role in the Bible (for example, Joseph dreamed that he should leave Bethlehem and take Mary and Jesus to safety in Egypt), and serve as a structure for literature (The Dream of the Rood; Pearl), but did regular people give much credence to their dreams? How did medieval illuminators represent dream sequences? Did they discuss them at holiday gatherings?

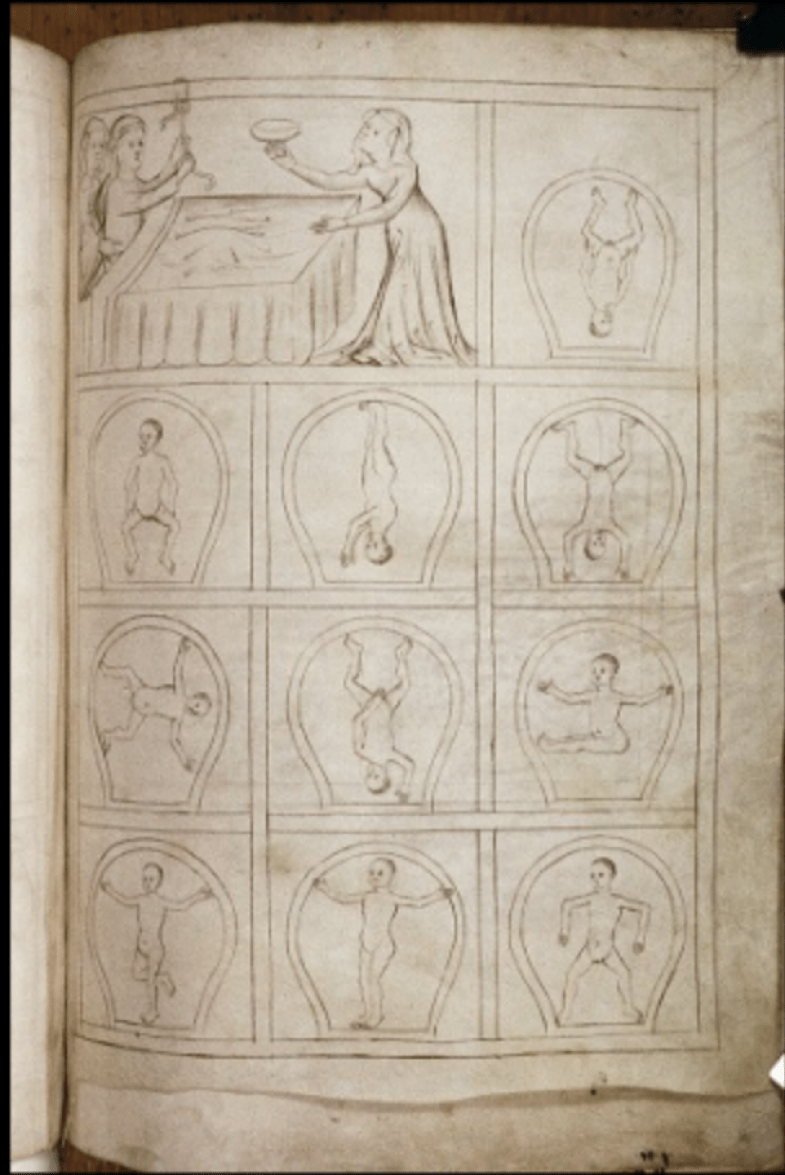

Period: Menstruation has become a fashionable topic, second only to global warming. So much so that women’s toilets in rural cafes around Scotland have baskets of free tampons to fight against period poverty. The likelihood of chatting about menstrutration is greater now that it has ever been. This could be your segue to medieval images of the bleeding wounds of Christ, which look vulvic and menstrual. You could expand the topic to include uteri, such as those represented in medieval diagrams of oddly choreographed fetal positions (Bodleian Library MS. Laud Misc. 724). There’s potential here to “dance your dissertation” by evoking these positions. Or turn it into a parlour game. Extra credit if you can work in menopause.

Money: Here you could think about medieval coins and forgeries. Or money in the sense of how various items were valued. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art recently mounted an exhibition of medieval objects, in which they did just that: they listed the original price of each item in terms of how many cows it would have cost. A panel painting only cost five cows, while a tapestry would have set you back 52 cows. How many cows did you spend buying holiday gifts?

Route talk: You think the the journey from London to Birmingham is epic on a holiday weekend, how about when Mansa Musa went from West Africa to Mecca? What kind of infrastructure did they encounter, and how did it handle the enormous entourage he brought? In the 13th century, what route did ivory take from what’s now Kenya to Paris, where it was carved into images of the Virgin?

Despite my jocular tone, there is also an opportunity to reveal something about the importance of the study of the Middle Ages: it often reveals aspects of ourselves, now.

Over the break, we can talk about awkward topics, including those that have some element of autobiography, when we add some time and distance to the topic. Not only do we learn about our past, but we learn about ourselves.

My challenge to you is to discover what your field of speciality can bring to dull small talk.

Kathryn Rudy is professor in the School of Art History at the University of St Andrews.