In the mid-2000s, Facebook, Bebo and Myspace were neck and neck in a frenzied race to attract the most users to their fledgling social networks. A decade later, Bebo and Myspace were moribund while Facebook boasted more than 1.5 billion monthly active users and its founder, Mark Zuckerberg, had become the fourth-richest man in the world.

Zuckerberg’s position is unlikely to be challenged by anyone founding a social network focusing specifically on academics. One of those people – Richard Price, founder and chief executive of Academia.edu – estimates there to be about 6 million academics globally, plus 11 million graduate students: a mere drop in the ocean of humanity that Facebook is fishing in. Nevertheless, there is serious cash riding on Academia.edu’s struggle with the likes of ResearchGate and Mendeley to be the biggest fish in that relatively small sea.

So far, San Francisco-based Academia.edu has reportedly raised $17.7 million (£12.5 million) from investors, including the multibillion-dollar venture capital firm Khosla Ventures. Meanwhile, Berlin-based ResearchGate has raised at least $35 million from venture capitalists and Microsoft founder Bill Gates. And London-based Mendeley also attracted significant investment before being bought by the giant publisher Elsevier for £65 million in 2013. According to Michael Clarke, president of Clarke & Company, a consultancy that specialises in the scientific and medical information business, figures such as these mean that “the bar for success is high” in terms of profitability.

The likelihood of that bar being surmounted depends crucially on user numbers. In terms of registered users, the biggest of the “big three” networks is Academia.edu. Founded in 2008, it has signed up more than 34 million “academics”, while ResearchGate and Mendeley – also launched in 2008 – have “more than 9 million members” and “more than 4.6 million registered users”, respectively. However, a major survey of academic social network usage, to be published on 15 April (see 'Who’s winning the battle for users? Dominance of ResearchGate' box, below) suggests that, in terms of active usage, ResearchGate considerably outstrips Academia.edu.

The organisers of the Innovations in Scholarly Communication survey, Jeroen Bosman and Bianca Kramer, based at Utrecht University library, say that this finding is borne out by the fact that searching for papers by a particular individual or department typically turns up more on ResearchGate than on Academia.edu. They say that the discrepancy between the survey results and the official usage figures may be explained by the fact that there are more lapsed or passive accounts – possibly set up by students – on Academia.edu; their survey asked “What researcher profiles do you use?”, implying active usage.

“The overall membership figures published by ResearchGate and Academia.edu are potentially very important in their marketing. This is not to say they are false, but they may not describe the full picture,” they say.

The phrasing of the question could also explain the very low reported use of Mendeley, which bills itself not so much a “researcher profile” site as a “reference manager”. Mendeley was also excluded from the automatic menu of responses, so respondents had to manually enter it.

Academic social networks allow researchers to post, share, collate and recommend papers. Researchers regard them as “a valuable way of getting publications online and making them publicly available, as it is often a lot quicker and less restrictive than the processes for depositing items in their institutional repository”, says Katy Jordan, who has interviewed academics on the topic for a PhD at the Open University.

Advocates hope that this process of making academics more rapidly and comprehensively aware of what peers are publishing will speed up the pace of discovery and potentially facilitate a revolution in peer review, with a paper’s quality being thrashed out by network users post-publication, rather than by a tiny number of referees pre-publication. And just as the Facebook newsfeed has transformed how people keep up to date with current affairs, some foresee analogues of this on academic social media sites having a similar effect on how academics keep up with developments in their own fields.

Data gathered through social networks could even be used to inform hiring and grant decisions. The Metric Tide, a major report released in the UK last year that looked at the use of metrics in assessing research, suggested that “over time”, social networking sites – including mainstream ones such as Twitter and Facebook – “might be developed to provide indicators of research progression and impact, or act as early pointers towards indicators more closely correlated with quality, such as citations”.

Be this as it may, why should academics care which, if any, network emerges victorious? To take the “if” question first, there is certainly an argument that one network would be better than many, given the effort required to keep them updated. “The thing that I have the biggest trouble with…is just how many of them there are, and how widely incompatible their datasets are,” says Michael Heron, a lecturer at Robert Gordon University. “At the same time, I don’t feel like I can ignore them – I’m an early career researcher, and I need to make my work visible.”

Then again, if one network did win out, users of the others would have to go to the trouble of switching to it. And even for those already on the winning network, the battle for supremacy could be a significant irritant given the ideas that the combatants are toying with in order to “monetise” usage of their sites.

These ideas are not something that Academia.edu’s founder Price is particularly eager to discuss, insisting that “we don’t know the future”. He has an unusual background for a Silicon Valley tech chief: he is a former fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, where he earned a philosophy DPhil as a prestigious Examination Fellow. However, even at Oxford, his entrepreneurial streak was apparent, prompting him, for instance, to set up Richard’s Banana Bakery, which sold banana cake, as well as a website called LiveOut for people looking to rent in the city.

Dismissing reports that Academia.edu is considering a stock market flotation, Price insists that the site is currently “absolutely not” profitable, despite making “some revenue” from advertising and job adverts. But clearly this is a situation that the company is hoping to change. For instance, at the end of January, Scott Johnson, an assistant professor of Classics and letters at the University of Oklahoma, received an email from Academia.edu asking whether he would consider paying “a small fee” for his papers to be “considered” for recommendation by other researchers on the network.

“You’d only be charged if your paper was recommended. If it does get recommended then you’ll see the natural boost in viewership and downloads that recommended papers get,” the email said.

Johnson posted the exchange on Twitter, and in the ensuing uproar asked: “If you are able to explain to me how I can pay for the promotion of my work and remain intellectually honest, please do.”

Consultant Clarke agrees that the “pay-for-promotion business model” is “half-baked” and “would backfire on anyone using it. Being perceived as paying to promote your work would not look good in the academic community – one would immediately question what is wrong with the work that it requires paid promotion.”

After the Twitter backlash, Price admitted that the idea was “silly” and claimed that the company had actually been trying to “start the conversation with users around how to fund academic publishing when paywall revenues dry up” and was “probing” the suggestion that Academia.edu could publish humanities papers for a “super-low cost” of about $50.

Price confirms to Times Higher Education that paid-for open access publishing is “one of the options” for increasing revenue. “The line between the social media platforms and the publishers are getting blurrier and blurrier,” he notes. But Clarke is sceptical about this idea too. “They would have to be extraordinarily successful as the article processing charge would have to cover not only the costs of publication but also the costs of running the network,” he says – while other open access publishers such as PLoS and Frontiers need only to cover their publishing costs.

Ijad Madisch, founder and chief executive of ResearchGate, also has doubts about the potential for academic networks to become publishers “in a traditional way”. Standard publishers provide three things, he says: reputation, quality control and distribution. But social networks do not have a reputation as established places to publish, and there are questions over their quality control.

Instead, Madisch – who came up with the idea for ResearchGate while working as a researcher at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston – is placing his hopes in advertising. He is aware of the criticism Facebook has received for what some feel are overly specific ads, offering users haemorrhoid creams, porn addiction help and hair regrowth therapies. But it is not his intention to allow advertisers to target “your private life and what you do in your free time”. Rather, he intends to make his pitch to scientific conference organisers and equipment manufacturers with the promise of the kind of highly targeted adverts that traditional journals are unable to offer because – he argues – they lack data on exactly who is reading them.

“Imagine you could click on a microscope mentioned in a paper and buy it,” he says, adding that $1 trillion a year is spent on science, with a “relatively small number of people” deciding how. He predicts that ResearchGate – which is aimed much more explicitly at scientists than Academia.edu – could break even on the basis of adverts alone. It should be profitable “soonish”, and a stock market flotation is “definitely an option” as it “would give us more money to expand”, he says.

As for Mendeley – originally launched by three German PhD students – the fact that it is now “part of a larger entity means it doesn’t need to create a surplus on a standalone basis to be sustainable”, according to Nick Fowler, managing director of Elsevier’s research management division. Hence, it is not under pressure to aggressively monetise. “We acquired it because it allowed us to expand the range of services” to users, Fowler says.

Elsevier is controversial among academics because of its historic opposition to open access, which many users of social networks are likely to be inclined to support. A campaign around the time of the takeover that advocated the mass deletion of Mendeley accounts even acquired its own Twitter hashtag: #mendelete. Nor did Elsevier enhance its reputation among open access aficionados when, later in 2013, it issued a series of “takedown notices” to users of Academia.edu, asking them to remove any papers to which Elsevier held the copyright.

According to Clarke, “There is a long tradition of academics sharing their papers. The publishers are not concerned about this at a smaller scale.” However, with networks allowing millions of academics to potentially disregard copyright and make their papers freely available, it has become a much bigger issue, he says.

Digital content platforms are protected from legal action under US law provided they remove copyrighted material when asked to do so. But the issue remains something of a fly in the ointment for networks given the fact that the majority of academic papers are still published under restrictive licences: “Venture capitalists are going to be a little squeamish about investing significant amounts of [further] money while the larger status of the business is in question,” Clarke says.

However, the networks themselves remain bullish. Academia.edu’s Price points out that academics can make their preprint manuscripts freely available even if the final article is under copyright, while ResearchGate’s Madisch claims that open access is an unstoppable trend that will ultimately see the copyright issue melt away.

Since the outcry from scholars in 2013, Elsevier appears to have decided to take a more softly-softly approach to enforcement. “We want to work with the research community [because] prevention is better than cure,” says Fowler. “We want to make sure researchers are clear about the guidelines [they agreed to] when they signed publishing agreements.” But even if publishers went back on the offensive and tried to remove all currently copyrighted material on ResearchGate, Madisch “wouldn’t mind” because “the articles can still be shared privately, and the discussion can still take place” on ResearchGate.

While open access advocates cast Elsevier as the villain in its clash with Academia.edu, the latter is far from immune from criticism from academics who object in principle to the intrusion of the profit motive into academic research and publishing. For instance, Gary Hall, professor of media and performing arts at Coventry University and one of the attendees of an event at Coventry last December called “Why Are We Not Boycotting Academia.edu?” (see 'Responsible enterprise: don’t give commercial operations free labour' box, below), objects to the fact that Academia.edu has been able to persuade academics to “work for it for free”. Another attendee, Kathleen Fitzpatrick, director of scholarly communication at the Modern Language Association, speculates that it plans to sell its users’ data to corporate interests in ways that they “may not approve of”.

This is a reference to the previously mooted idea that academic social networks could sell usage data to pharmaceutical companies, for instance, to give them an early warning about what scientists are interested in. Neither Madisch nor Price expresses any enthusiasm about this idea, but Fitzpatrick insists that a non-profit alternative to the for-profit platforms is necessary to give users “a sense of control and confidence”.

The question, according to Clarke, is who would fund such a platform. One possibility is that a consortium of universities could simply buy an existing network, particularly if investors lost interest and it was sold off cheaply. But Price notes that the “experimentation” required to perfect a social network does not come cheap, and that “there’s vastly more capital in the private market”.

Some may question how transformative academic social networks could ever be, given the pressure that academics are under to engage with the general public, as well as their peers. According to Jordan, academics on Academia.edu and ResearchGate “largely connect with people they already know”. By contrast, “Twitter is seen as a site that fosters novel professional connections more readily, and facilitates engagement with a wider range of audiences”.

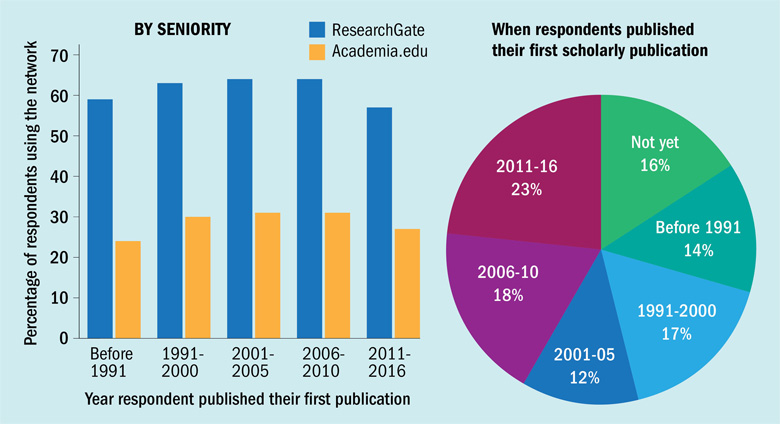

However, the usage figures indicated by Bosman and Kramer’s survey suggest that academic social networks could indeed be set to become big players, with nearly two-thirds of survey respondents using ResearchGate and nearly a third using Academia.edu – proportions that, interestingly, hardly vary with how long ago they published their first paper. And if the networks do take on a central role in research discovery and assessment, their discovery algorithms would acquire huge influence over academic life.

Bosman, a subject librarian for geosciences, says that transparency would be hugely important in such a scenario, noting that “there are lots of things we don’t understand” about why certain stories appear on Facebook newsfeeds. However, he believes that filtering papers should remain an academic activity, and he worries that relying on a mechanised process could lead to “tunnel vision” – an excessive focus on the most popular papers – to the detriment of other gems.

His own inclination is to ignore recommendations from social networks when deciding what to read: “It’s much more interesting to go for articles that haven’t been read,” he says.

Who’s winning the battle for users? Dominance of ResearchGate

Although Academia.edu officially has four times as many registered users as ResearchGate, a major survey of academics, students and research users and support staff to be published on 15 April suggests a very different picture.

The survey, Innovations in Scholarly Communication, was organised by Bianca Kramer and Jeroen Bosman, based at Utrecht University library. Open from May 2015 to February 2016, it attracted 20,670 respondents from across the globe, disciplines and pay grades.

The respondents are self-selecting but, according to Kramer and Bosman, the survey’s broad distribution, with a big role for organisations such as universities and publishers, means that there is “no reason why [respondents] would be primarily biased towards users of academic social networks”. The survey should be “useful for determining the overall degree of membership of academic social networks”, and for assessing which are the most popular networks among those who use such sites.

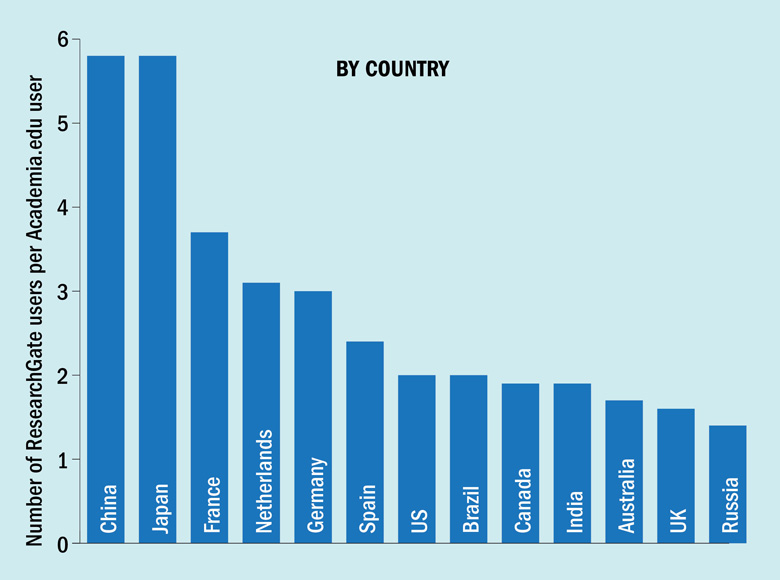

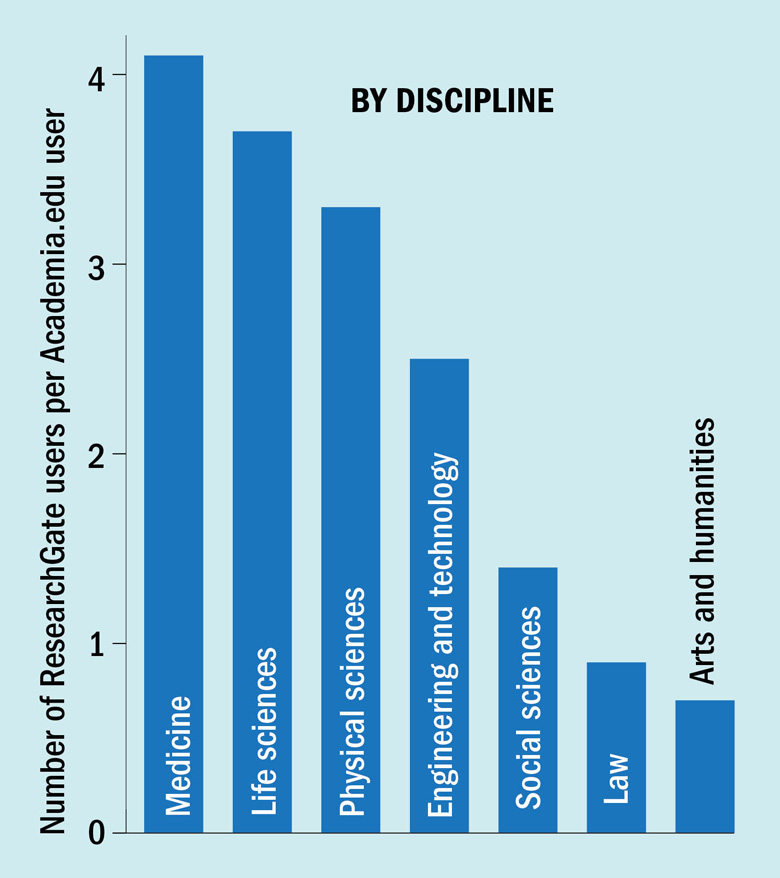

The results suggest that ResearchGate is more than twice as popular as Academia.edu. Usage of ResearchGate particularly outweighs that of Academia.edu in China and Japan, in the sciences and among the most senior researchers. Overall, 61 per cent of respondents who have published at least one paper use ResearchGate, while 28 per cent use Academia.edu, and just 0.2 per cent apparently use Mendeley.

Responsible enterprise: don’t give commercial operations free labour

Academic social networking sites are extremely popular with scholars. But Academia.edu, in particular, has recently received some sharp criticism from bloggers, including Gary Hall, Kathleen Fitzpatrick and Guy Geltner.

The comments focus mainly on the networks’ business models. The level of backing that Academia.edu has received from venture capital means that it will have to make a profit at some point, but the options seem to be limited. One would be to start charging fees for access to the platform. Another would be, like Facebook and Google, to sell ads or user and research data and analytics. A third would be to move into the highly profitable academic publishing market.

Suspicions that Academia.edu has opted for the latter were stirred by its launch of a new feature, called the Editor Program or PaperRank. This allows selected scholars to recommend papers, which are then given a score based on the number of recommendations they receive. It will enable the platform to start offering what it is positioning as a speeded-up and “crowdsourced” peer-review service. Its heavily criticised proposal to allow researchers to pay to have their papers considered for recommendation could presage further steps down this road to profitability.

Academic social networks typically present themselves as proponents of open access, and many of their members assume that the papers they post on them will be freely available. Yet, as a number of librarians and repository managers have pointed out, the barriers imposed by both Academia.edu and ResearchGate on the reuse of user profile data, the downloading of documents and the use of open licences mean that they do not meet the requirements of standard open access policies.

Such criticisms led to an event at Coventry University in December to explicitly address the question: “Why Are We Not Boycotting Academia.edu?” One issue raised by speakers concerned whether we should put our research and data – and with that our academic labour – into the hands of companies whose primary goal is not to help academics to communicate but to monetise that communication in the interests of investors.

One suggestion was that we should try to work with the platforms, to make them both more compatible with open access and more transparent and accountable. But many others worried that this might end up strengthening the specific vision of open access that the platforms (alongside many commercial publishers and funders) are promoting. This sees open access as offering not so much an alternative to the corporate model of scholarly publishing as a system of monetisation designed to stimulate the knowledge economy.

Building a more ethical publishing system based on a distributed commons with shared governance is something to strive for. Let us therefore use our labour to support not-for-profit, institutionally supported alternatives to commercial social networking platforms.

Janneke Adema is a research fellow in digital media at Coventry University and was chair of the “Why Are We Not Boycotting Academia.edu?” event. Videos of the event are available here.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Does your research need ‘likes’?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login