On a sunny afternoon in mid-March, the near-carless peace of central Leiden is perturbed by the sound of distant sirens. In Utrecht, a city less than an hour’s drive away, three people have been killed by a Turkish-born gunman in a suspected terrorist attack, and there are huge numbers of police at Leiden station. But Leiden’s canals and cobbled lanes remain a picture of the Dutch Renaissance; a white flag bearing the number 444 in red script flies from Leiden University’s clock tower, commemorating the palindromic anniversary of the foundation of the Netherlands’ oldest university, in 1575.

The long history of universities in the Netherlands – the universities of Amsterdam, Groningen and Utrecht were next to be founded, in the early 17th century – is one explanation for their prominence. However, diversity and egalitarianism are also strengths of the Dutch university sector, in which ancient universities are complemented by more modern or specialist institutions, also highly regarded. These include the Eindhoven University of Technology – at the heart of a booming regional “innovation ecosystem” led by locally based multinational technology firms such as Philips – and Erasmus University Rotterdam, named after the 16th-century father of the Northern Renaissance, who was born in the port city but who would struggle to recognise its gritty, post-war reincarnation, the antithesis of nearby Leiden.

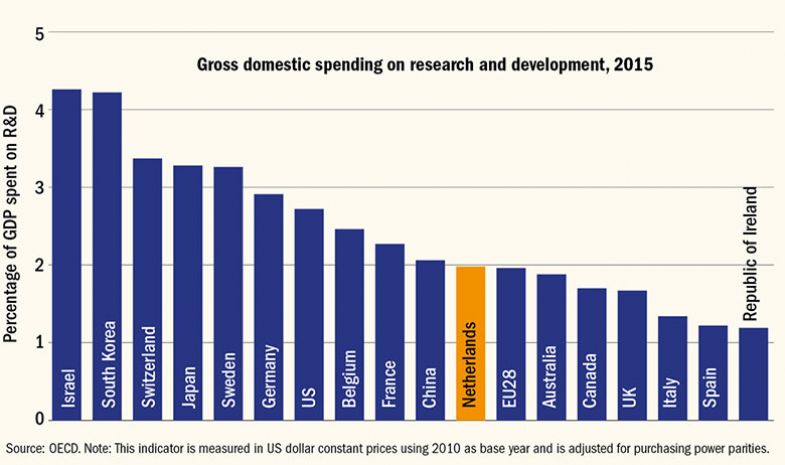

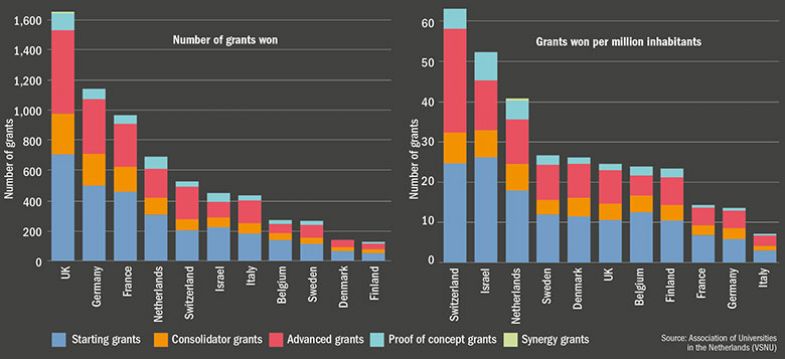

Taken as a whole, the Dutch university system is a stellar performer. In terms of prestigious European Research Council grants won, only Europe’s three most populous nations – the UK, Germany and France – outperform the Netherlands, a nation with a population of just 17 million. And when the figures on awards between 2008 and 2017 are adjusted for national population size, Switzerland, Israel and the Netherlands lead the rest by a distance, according to figures from the Association of Universities in the Netherlands (VSNU). The country’s performance is all the more noteworthy considering that its R&D spending is modest, exactly in line with the European Union average of 2 per cent of GDP and well behind Switzerland and Israel (see graph).

“The Dutch, like the Brits, get much more out than they put in – like the Swiss or the Israelis,” says Robert-Jan Smits, Eindhoven’s president and, in a former role as the European Commission’s director general for research, one of the architects of the ERC. “This all proves that the [Dutch] system is performing extremely well.”

That verdict is underlined by the fact that 12 of the Netherlands’ 13 mainstream universities (the country also has an open university and 43 universities of applied sciences) are ranked between 58 and 184 in Times Higher Education’s latest World University Rankings.

Pieter Duisenberg, the VSNU chair, says: “We have these 14 universities in a very compact regional cluster, and cooperation…is really a core activity, within the Netherlands [and] internationally.”

Such consistency of performance is a result of the fact that the Netherlands is “a pretty egalitarian country – every university gets the same funding” from the government and there is no US-style culture of philanthropy, says Carel Stolker, rector magnificus of Leiden University. And he is “fine” with Leiden’s 68th place. “Maybe if you gave me more money I can become better, maybe enter the top 50 of the world. But who cares whether it’s number 50 or number 100 or number 70?” he asks.

The egalitarian spirit is also reflected in Dutch universities’ relative lack of selectivity at undergraduate level. Completion of the post-high school diploma earns students the right to enrol, and selection is only employed for the 11 per cent of courses where demand exceeds the number of places.

But the sirens are audible figuratively as well as literally, at Leiden and across the nation’s university sector. One major concern is funding. Dutch institutions’ prowess at winning EU grants is just as well, given the relative paucity of funding on offer domestically, critics claim, with the amount of competitive funding won from Brussels now outweighing the amount offered by domestic funders the Dutch Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences (KNAW).

Moreover, the government’s direct block grant of €4.2 billion (£4.9 billion) a year – 53 per cent of which is for teaching and 47 per cent for research – has declined by 25 per cent since 2000 on a per-student basis as enrolment numbers have increased. There is a growing feeling that such a trend can no longer be sustained without a dilution of standards – particularly given the near-universal reluctance in the Netherlands to raise tuition fees from their relatively low level (at least by UK and US standards) of €2,060 (£1,769) a year in 2018-19.

“The success we have now is based on the policy and the infrastructure of 10-20 years ago,” says Martin Paul, president of Maastricht University. His home country of Germany is ploughing billions of euros into its Excellence Initiative in research, risking the creation of “a reverse stream” of researchers away from the Netherlands into its larger neighbour, he warns.

Smits notes the EU’s target for member states to raise their R&D spending to 3 per cent of GDP by 2020. There are “good kids in the class” who have hit the target: Germany, Austria and Sweden. But although the Netherlands is now achieving budget surpluses, it is “still a very Calvinistic country and people don’t like to spend money”. The government needs to realise that research spending is actually “investing”, Smits says.

A spokesman for the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science agrees that "public and private investment in R&D are crucial to future economic growth in the Netherlands. Due to the structure of the Dutch economy, the Netherlands has, since 2011, set a target of 2.5 per cent on R&D spending." To that end, he adds, the government will, from 2020, "invest up to a total of €400 million extra in research and innovation" and "is encouraging increases in private spending". He concedes that, in terms of direct funding for universities, “the trend of the total budget per student (education and research) is decreasing for research universities”. But “if only the educational budget is taken into account, the educational budget per student has increased between 2004 and 2017 and will continue to increase from 2018 onwards”.

The widespread concern about funding levels culminated in the first university strike in the Netherlands’ history on 15 March, which brought 40,000 schoolteachers and academics on to the streets of The Hague. It was led by a group of students and academics, known as WOinActie (“Science Educators in Action”), formed in 2018 in response to the government’s imposition of a €184 million “efficiency cut”. According to the group’s founder, Rens Bod, a professor of digital humanities at the University of Amsterdam, overburdened academics worry that “they cannot any longer give students what they need”. The group plans further lobbying of members of parliament; if that does not succeed, more “drastic” action will be mounted: “something like a strike during exam week”, Bod says.

Academics “do not go on strike very easily”, adds Duisenberg, the VSNU chair. “The fact that they are [doing so] is something we have to take very seriously.”

But some Dutch politicians seem less concerned about funding problems than they do about Dutch universities’ enthusiastic embrace of internationalism, which they see as a threat to native culture.

In 2017, there were 48,507 international students in the Netherlands (about 71 per cent of whom were from the EU), equating to 17.5 per cent of all university students. Such recruitment levels have been enabled by a widespread use of English as the language of instruction. In 2018, 30 per cent of undergraduates at Dutch universities were taught solely in English, 23 per cent in both Dutch and English and 47 per cent solely in Dutch, according to VSNU figures. However, at master’s level, 71 per cent of students were taught solely in English.

At Erasmus University Rotterdam, for instance, even the campus signage is all in English. You will search in vain for the Dutch translation of “faculty club” or “food plaza”. Rutger Engels, the institution’s rector, says this reflects institutional pride in its status as “the most diverse university in the Netherlands”, with more than 100 countries represented on its ultra-modernist concrete campus, in a city where 50 per cent of the population are immigrants.

Dutch researchers also started to publish in English “longer ago than some countries, like Germany or France or Italy”, in order to collaborate with colleagues abroad, Engels adds. Such international outreach is “in the mindset of Dutch professors”. But critics fear that as well as threatening to make the Dutch language obsolete, more teaching in English means ever greater numbers of international students and a mounting risk that Dutch students become crowded out.

European Research Council performance, 2008-17

If there is a defining battleground in the controversy over the use of English in Dutch universities, it is at Maastricht, where international students make up about 53 per cent of the student body. The university is based in the historically Catholic deep south of the Netherlands, in a city whose proximity to Belgium and Germany gives it a very different look and feel to its counterparts in the historically Protestant north.

After years of campaigning, the lobbying group Better Education Netherlands (BON) filed a lawsuit against Maastricht and the University of Twente last year, arguing that their decision to offer psychology degrees in English breaks a law stipulating that teaching and exams should be in Dutch except when there is an educational reason to do otherwise. BON argued that the universities’ motives for using English were, in reality, financial. However, in July, the court accepted Maastricht’s contention that psychology is international in nature since those who expect to go on to become researchers will have to communicate their findings in English.

Paul notes that there is the option for Maastricht students who expect to become practitioners to take their psychology degrees in Dutch. But such concessions are unlikely to assuage the likes of former Leiden law lecturer Thierry Baudet, the 36-year-old leader of the anti-multiculturalism, anti-EU party Forum for Democracy (FvD), who – against expectations – won the largest share of the votes in the Netherlands' provincial elections on 20 March (although that amounted to only 14.5 per cent of the total). Those elected to the country’s 12 provincial legislatures go on to choose the members of the Netherlands’ upper house of parliament, the Senate, two months later.

In his campaigning, Baudet made great play of the Utrecht attack, which occurred just a few days ahead of the election. And in a victory speech, he included universities among the supposed leftist elite forces that have “undermined” Dutch civilisation – “the greatest…that ever existed” – accusing them of having “abolished” the use of Dutch. His party subsequently announced a “hotline” for supporters to report examples of supposed left-wing “indoctrination” in schools and universities.

All this illustrates how deeply political the language debate has become. Prior to the conclusion of the BON court case, the dean of Maastricht’s Faculty of Psychology and Neuroscience, Anita Jansen, published a blog on the university’s website accusing Ad Verbrugge, the BON chair, of pursuing a “right-wing populist struggle” and of being a Baudet sympathiser. Verbrugge, a Leiden PhD graduate in philosophy and an associate professor at VU Amsterdam, was reportedly associated with the FvD in its former guise as a thinktank (it became a political party only in 2016).

For Paul, the debate over teaching in English is “a fake discussion”. In reality, he argues, it is not about teaching but about “a general societal worry that the threat comes from outside and that internationalisation, globalisation is the threat” – even though international companies based in the Netherlands need staff with good English, while there are vacancies in Dutch science and engineering companies that can only be filled by overseas graduates.

Stolker notes that “a lot of Dutch students want to study English courses because they believe it helps them in terms of their employment prospects”. But it is “challenging…for the broader public at large to understand that added value”, he admits. “And language is identity.”

In May, the VSNU issued a new internationalisation strategy, in the context of which, Dutch universities thinking of switching a Dutch-language programme to English will coordinate with others to ensure that at least one Dutch-language version of each bachelor’s degree remains available somewhere in the country.

In response to the controversies, the Netherlands’ ministries of education, finance and economic affairs are currently carrying out a cross-departmental study on the value of internationalisation in universities. Paul says that the study’s agenda is “not hostile” to universities, but it is unclear what the make-up of the governing coalition will be when the report is published – and, hence, how it might react. The spokesman for the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science says that the “main aim” of the study is to “identify opportunities and threats of student mobility (in particular, incoming student mobility) and to propose policy and/or measures that enlarge [its] positive effects…and decrease or mitigate the negative effects.”

“Our biggest challenge is if there would be legislation against internationalisation,” Paul says.

Australia, Germany and the Scandinavian nations “see the international [student] influx as essential to maintain their economic power,” he argues. It would be “tragic" if "the Netherlands, which has been the front-runner on this, [now] does the opposite”, he adds.

Condemnation of Baudet’s victory speech was widespread among higher education figures, including Ingrid van Engelshoven, minister of science, education and culture and a member of the centrist Democrats 66 party. In a tweet, she described Baudet's attack on universities as "nasty" and said: “Society is built on the work [and] knowledge of scientists [and] lecturers. We must protect academic freedom, not make it suspect.” Meanwhile, Paul responded to the establishment of the FvD “indoctrination hotline” by telling THE that “as academic communities, we need to take a strong stand against anybody who is trying to undermine our academic principles”.

But before Baudet’s win, there was already a debate over free speech and ideological bias in Dutch universities. Curiously, the VSNU’s Duisenberg was a key figure here since, in his previous role as a member of parliament for the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy (VVD), which leads the governing coalition, he was co-proposer of a motion passed in 2017 by the Netherlands’ lower house that asked “the government to request advice and consideration” from the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences about “self-censorship and limitation of diversity of perspectives” in universities and research institutes. But, when asked by THE, he insists that he does “not have an agenda” on free speech and ideological diversity.

The academy voluntarily responded to the motion, issuing an advisory memorandum – based on anecdotal examination of notable controversies – that found “no signs of any systematic restriction” on “freedom of scientific practice”.

But Leiden’s Stolker, a prominent defender on free speech in universities, points to the case of Afshin Ellian, a professor of jurisprudence at Leiden, as well as a newspaper columnist and high-profile critic of Islamism. “When he teaches – whatever he does – there is always [the necessity for] security around him,” says Stolker. He also cites controversy over classroom discussions of Turkey and China. “So I think freedom of speech is an issue,” he says. The academy's report was “too easy” on the sector, he believes.

Leiden has professors with radically differing political viewpoints who are “very vocal” on mainstream and social media, Stolker continues. “Again and again people ask me to intervene as a rector.” This also extends to questions about Baudet. People ask him: “How is it possible he did his PhD at Leiden: don’t you feel responsibility for what he is doing now?”

But Stolker responds that he does not have a position on the political views of Leiden academics. Moreover, as rector, he is “responsible for free speech in this university”. Leiden has a long-standing tradition of appointing “adversaries” with different viewpoints to professorships. “I very much feel responsible for that tradition,” says Stolker.

Nevertheless, Stolker tweeted in response to the FvD “indoctrination hotline” that it was an “idiotic” attempt to attract attention.

Stolker also gets pestered about Paul Cliteur, professor of jurisprudence at Leiden, who was co-supervisor on Baudet’s thesis and is another columnist and high-profile critic of Islamism and multiculturalism. Cliteur was the number two on the FvD’s list of candidates, so will be taking his seat in the Senate.

Cliteur has his own definition of diversity. While his current PhD candidates include a “liberal Muslim”, he is “not on the lookout for [students] with a different skin colour specifically. Because I think that’s not a good criterion for diversity. Ideological diversity – that’s what counts in a university…We should be against identity politics.”

He says that “80 per cent” of Leiden scholars are left-wing: “Is that diversity?” he asks. And while “in general, Leiden University is a very tolerant – in the best sense of the word – community, I do not think that Amsterdam University would be that tolerant”.

Cliteur confirms that Baudet’s political movement had its “cradle” in his Leiden PhD thesis, published as a book in 2012 under the title The Significance of Borders: Why Representative Government and the Rule of Law Require Nation States. “The multiculturalist philosophy is an assault on national coherence, and it’s dangerous,” he adds.

Despite his academic background, the FvD leader directs his attacks on supposed cultural elites “more strongly than most other populists” towards higher education institutions, according to Matthijs Rooduijn, an assistant professor of political science at the University of Amsterdam, who blogged an analysis of Baudet’s victory speech.

“This message also fits well with his climate change scepticism…He hopes to mobilise ‘ordinary citizens’ against conspiring and left-wing elites that, according to him, are destroying our cultural identity,” Rooduijn adds.

And even if the FvD hotline does indeed prove to be nothing more than a publicity stunt, Baudet’s anti-university rhetoric is worrying, says Leo Lucassen, a high-profile commentator on the left and director of the International Institute of Social History at Leiden, where he is professor of global labour and migration history. “It buttresses or creates a climate of intimidation or fear in Dutch society. What he is doing is undermining trust in institutions in general.”

Another paradox of Baudet’s university association is that he consciously seeks to “exude the aristocratic air of a Leiden University fraternity member” – as an article in The Nation magazine recently put it – in what may be part of an attempt to appeal to university-educated voters. Exit polling after the election suggested that about 29 per cent of FvD voters have a higher education – below the 35 per cent of the general population “but high for a European radical right-wing party”, according to Dutch newspaper NRC Handelsblad.

Baudet’s “dandy image, being an intellectual, helps certain people who are higher educated to vote for him”, Lucassen agrees.

Baudet’s success follows the second place achieved in 2017’s general election by Geert Wilders’ right-wing populist Party for Freedom and cements the sense that this brand of anti-elitism is an increasing force in Dutch politics. In such a climate, the risks posed by the language controversy may be sharpened further, with Dutch universities repeatedly targeted as part of “the globalist elite”, divorced from the cultural identity of “the people”.

There also may be questions over whether, given the relatively civilised debate on free speech at a place like Leiden, Dutch universities are prepared for an all-out, US-style culture war. But although a white flag may be flying from Leiden University’s clock tower, Dutch universities are not without their own armoury given the high public esteem that they have built up over more than four centuries, with many of their academics enjoying high profiles in the Dutch media as commentators.

They will also receive large amounts of moral support from other nations, which have always admired the Dutch higher education system’s international outlook and the success that has come with it. If the global tide of populism can breach even the tolerant Netherlands' socio-political dykes, they may well reflect, then universities everywhere should worry.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Will populism drown Dutch internationalism?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login