When Dwight Eisenhower began his tenure as president of Columbia University in 1948, he was immediately thrust into a controversy. The university had appointed renowned scholar Manfred Kridl as an endowed chair for the study of Polish language and literature. The position was funded by the Polish government, but the Polish-American Congress claimed that it was part of a Russian “academic infiltration” campaign and demanded that the funding be rejected.

Eisenhower was new to academia, but did not shy away from the public debate. He stood squarely in defence of academic freedom, saying at his inauguration that “there will be no administrative suppression or distortion of any subject that merits a place in this university’s curriculum. The facts of communism, for example, shall be taught here…no intellectual iron curtain shall screen students from disturbing facts.”

Eisenhower’s stand is part of a long history of educational institutions engaging with the public debate about issues of consequence. By the end of the 1980s, for example, about 150 US educational institutions had divested from apartheid South Africa. In the previous decade, universities played a key role in efforts to end the Vietnam war. Eisenhower is also part of a tradition of individual university leaders both weighing in on political issues and standing for political office. In successfully running for the presidency soon after assuming leadership of Columbia, he was following in the footsteps of former Princeton president Woodrow Wilson, whose effective administration of university affairs led to his successful candidacy for New Jersey governor and, eventually, president.

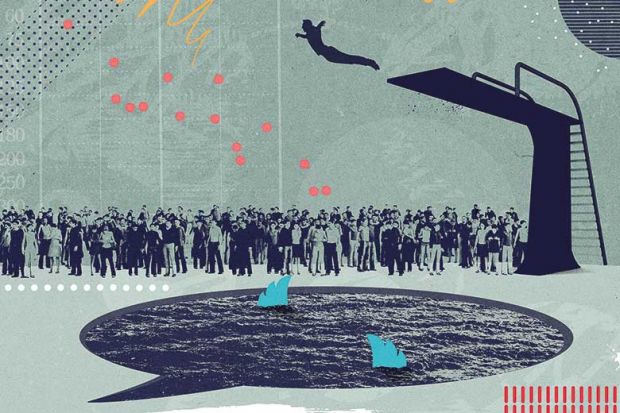

But it is now substantially less common for university leaders to engage with public debate, much less run for office themselves. In the 1990s, John Silber, then president of Boston University, ran for governor of Massachusetts, but his is an isolated (and unsuccessful) example. Indeed, former Harvard Medical School dean Jeffrey Flier recently argued in Times Higher Education that university leaders cannot be public intellectuals. His core reasons are that the modern demands of administration make it hard to find the time, and that our increasingly polarised discourse has amplified the perils of such engagement.

These concerns are valid. It is true that Twitter can lend itself to sudden spasms of mass opprobrium, but it is just one of myriad modern technologies that make it easier than ever to reach an audience: from podcasts and YouTube to online publications and Facebook Live. The trick, for university leaders, is to choose the medium with care. Even within Twitter's character limits, it is possible to link to articles that provide a deeper dive into complex issues, making space for more reasoned, less instantly reactive debate. I will promote this article, for instance, with a tweet or two from my personal account, which will allow others to see both Flier’s argument and my response. An effective point and counterpoint, efficiently produced and broadcast in a flash: this is what technology offers, and it is an opportunity that university leaders could seize in these turbulent times.

As the concept of truth itself comes under attack, and ideas are judged solely by what they contribute to the economic marketplace, the primacy and inherent value of facts, which are the foundations of the academic enterprise, must be defended. Individuals in other sectors are already jumping into the fray. Chief Justice John Roberts publicly corrected President Donald Trump’s characterisation of a judge who ruled against his administration as an “Obama judge”, stating that “we do not have Obama judges or Trump judges…what we have is an extraordinary group of dedicated judges doing their level best to do equal right to those appearing before them.” Businesses, too, are taking stands on issues of consequence, as Delta Air Lines did when it opted to cut ties with the National Rifle Association after the Parkland shooting. What excuse do academic leaders have for standing down when threats to our core values emerge?

Moreover, when they do so, they risk falling behind their communities. During my four years as dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, our students and staff have mobilised over a range of issues, from gun safety reform to transgender rights. Turning a deaf ear to such internal conversations would be an untenable position for a leader of any institution.

Flier is right that the skills that help people rise to positions of academic leadership do not always make for instinctive participation in the national debate. But we are living in a moment of cultural and political transition, and academic leadership must change with the times, or be left behind by them. Moreover, we have a moral responsibility to use our voices to influence the conversation for the better. Here, the Kridl imbroglio is again instructive. Perhaps sensing the attitudes of intolerance that would fuel the rise of Joseph McCarthy just a few years later, Eisenhower found his voice. As we tackle the challenges of our own time, we should aspire to nothing less.

Sandro Galea is professor and dean at the Boston University School of Public Health. His latest book, Well: What We Need To Talk About When We Talk About Health, will be published in May.

后记

Print headline: University leaders have a duty to engage with public debate