Academics are naturally divisive creatures. Yet they seem agreed that something called “neoliberalism” is the ultimate source of their common woes – with both their university administration and society more generally.

Neoliberalism’s signature policy instinct is to convert monopolies into markets, resulting in more competitive environments. It first emerged among economists in the early 20th century, amid the takedown of the corporate monopolies perceived to be restricting new entrepreneurs’ market access and stifling innovation more generally. The original neoliberals were progressive, in the spirit of Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson. However, once Wilson imposed a national income tax (partly to finance US involvement in the First World War) these same economists worried that the state might itself become the new corporate monopoly.

The spread of broadly socialist policies over the next few decades, including the New Deal and the welfare state, turned this misgiving into neoliberalism’s dominant theme. By the time it became the house ideology of the Reagan and Thatcher governments in the 1980s, it was focused on divesting the state of its powers over the provision of health, education and other welfare services. “Marketisation” now became the state’s main business.

Neoliberalism arrived in UK higher education as early as 1963, with Lionel Robbins’ landmark report. This offered a strategy for breaking Oxbridge’s long hegemony via the creation of US-style campus-based universities specialising in social science and other “modern” subjects. Thirty years earlier, Robbins had hired neoliberal luminary Friedrich Hayek at the London School of Economics.

A less capital-intensive follow-up was the 1992 “new universities” legislation, which upgraded the status of existing polytechnics and teachers’ colleges to swell the ranks of people entering university.

It is difficult to deny that this approach – with its audit regimes for research and teaching that place all universities in the same competitive pool – has helped level the playing field in higher education. Indeed, neoliberalism generally isn’t given sufficient credit as an effective democratiser. Perhaps that’s because neoliberals have tended to turn a blind eye to past damages. Instead of penalising past winners through taxation – seen as an illicit form of restorative justice – neoliberals invest conditionally in prospective future winners.

The underlying psychology here seems sound, helping to explain the global appeal of neoliberal policies, which cut across traditional social, political and economic divisions. It is based on intuitive notions of fair play: people prefer to lose after they have been given a chance to win than to have a victory subsequently taken from them.

But why, then, are academics in particular so antagonistic? The answer is that neoliberals are more principled in their hostility to inherited privilege than academics are. The latter’s authority over their field of knowledge is tied to mastery of a discipline-based “expertise” that is the legacy of a specific line of researchers over many years, if not generations. Acquiring such expertise – and its associated jargon – entails substantial entry costs, ranging from attending the right schools to accessing the right funds.

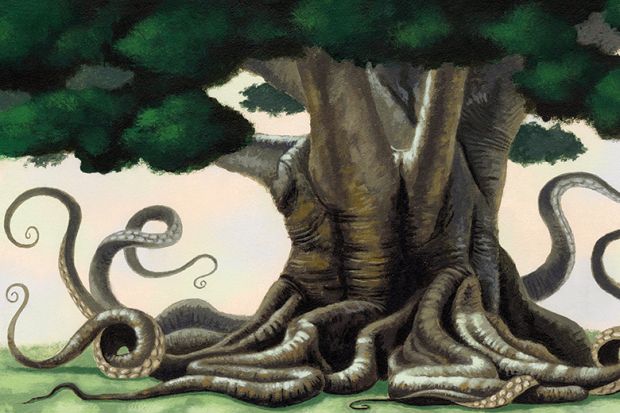

Academics generally wear all this as a badge of honour but, to neoliberal eyes, the arrangement looks like a mutually reinforcing system of information bottlenecks, resulting in an artificially maintained hierarchy of “knows” and “know-nots”. It is the intellectual version of the ultimate economic evil, rent-seeking: a phrase inspired by David Ricardo’s – and later Marx’s – disdain for landowners who increased their land’s value simply by restricting access to it, rather than using it productively.

In response, academics say that restricted access ensures high-quality knowledge. But, like other claims to elite privilege, this assertion is self-serving unless it can be put to a test in which the academic establishment is not pressing its thumb too hard on the scale. Thus, the recent UK Higher Education and Research Act allows non-academic actors to compete on the playing fields of research and training if they have already shown a capacity to deliver such “services”. More generally, neoliberal policies promote the use of altmetrics as an independent check on the club-like character of academic peer review, while requiring academics to court extramural constituencies.

Yet, compared with other sectors of society, higher education has tended to respond to these “market challenges” in unimaginative, if not reactionary, ways. Academics appear wedded to the idea that the delivery of high-quality research and teaching in the future depends on the means by which they have been delivered in the past. Thus, their proposed “innovations” tend to be marginal, such as putting academic lectures online, publishing in open access journals and serving up the same courses in less time.

There has yet to be anything in the higher education market comparable with the creative destruction wrought by the motor car’s replacement of the horse as the primary mode of personal transport 100 years ago. That innovation required a much more radical rethinking of means to ends than self-described “radical” academics appear willing to engage in today.

Steve Fuller is professor of sociology at the University of Warwick and author of Post-Truth: Knowledge as a Power Game (Anthem). He will be debating with Philip Mirowski at Lancaster University on 24 July about whether neoliberalism can lead to a positive future for the university.

后记

Print headline: Academic monopolies are nothing to be delighted about