View the results of the overall THE University Impact Rankings 2019

The United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals set out 169 targets covering all aspects of life on Earth, in all countries – people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership. Meeting these targets involves change – social change, political change and industrial change – but most of the problems embedded in the SDGs are complicated and complex, for which solutions are hard to find, the effects of interventions hard to predict and success hard to transfer and scale up.

Achieving the goals presents massive intellectual and practical challenges. Of course, universities are reservoirs of the practical and intellectual capital needed for the task, and it is recognised that these institutions must play a bigger role in helping to deliver SDG targets. Yet there is little evidence of widespread action, for many reasons, not least the institutional divisions and barriers that hinder the necessary multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary activities.

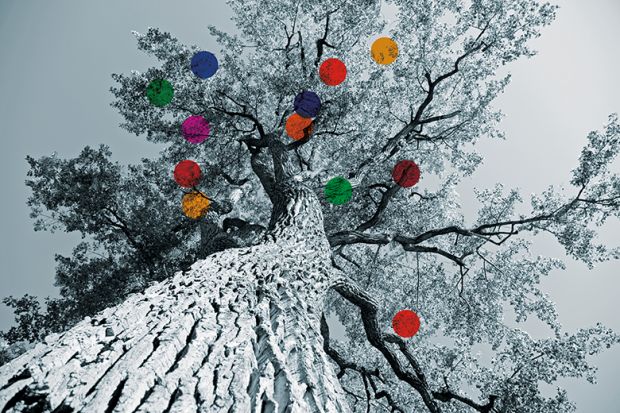

Therefore, universities must also change. The concept of the “SDG TREE of Change” encapsulates the transformations required of each institution in four core activities – training, research, engagement and enterprise – and is a rallying call for collective action across the world. The tree grows from and is nourished by all sectors of the institution – academic staff, professional services staff, students and alumni – working together and collaborating with other institutions and external bodies, to cultivate SDG fruit.

Training

Empowering scientists, engineers and social scientists to become the sustainability leaders of the future

New approaches are needed to the teaching of undergraduates and to the training of postgraduate students and early career researchers, in all disciplines – science, engineering, medicine, social science and the arts and humanities. Courses and training programmes should encourage participants to look outwards beyond the detailed nitty-gritty of their own research or degree courses and to interact with their peers in other disciplines and engage with the SDG challenges.

Institutions must develop imaginative structures and mechanisms that give students and researchers the opportunity to learn the broad knowledge base and skills required to become leaders in SDG delivery. Synthesising and presenting evidence, interacting with the media, and liaising with industry and policymakers are just some of the skills essential for such empowerment.

Research

Discovering innovative and practical solutions through advanced technology and transformative social change based on academic excellence

Harnessing academic excellence for SDG delivery is not straightforward. Unprecedented levels of cooperation are required – it is essential to share what works, where and when, but also what does not work.

There must be allowance for risk-taking and encouragement for new thinking and interdisciplinary working. Researchers should build delivery of specific SDG targets into their projects, rather than merely demonstrating post hoc that the findings can be mapped on to particular SDGs.

Key to this will be finding ways to co-design into research projects multidisciplinary approaches that translate the outputs of basic research into the practical outputs needed to meet specific SDG targets. This demands fundamental cultural change in the practice and the funding of research.

Engagement

Informing and influencing society, governments, NGOs and policymakers

Action to deliver on SDG commitments requires that all of society and its institutions are on board; thus, universities need to effectively engage with and influence them all. Universities are only beginning to comprehend this. Communication and engagement must be intrinsic elements of research projects. Evidence derived from scientific investigations should be considered in the context not only of other evidence on that topic but also of the associated political, cultural, economic and social dimensions. We need not only to synthesise evidence but also to understand it and learn the best ways to visualise and share it if we hope to change public attitudes and to shape policies. Web-based events, online publishing and social media platforms are becoming the norm, and universities need to learn how to operate more effectively in this space. We have to understand why some issues grab public attention, facilitating rapid policy intervention (such as single-use plastics) while others of much more importance and urgency (such as climate change) do not.

Enterprise

Working creatively in partnership with the public and private sectors locally, nationally and internationally

As delivery of SDGs requires action in both the public and the private commercial sectors, universities must work with both. We need new models of academic/business collaboration in which the participants work together, not in isolation. Establishing mutual trust is key. Academics need to learn the tight timescales and finances that govern business operations, while businesses need to better understand the motivations and working patterns of university researchers.

SDGs will ultimately be implemented at the local level in individual small companies or government departments and within communities and their environments. Universities can start by implementing SDGs in their own institutions, and then engage with businesses and government officials in their local towns and cities, spreading expertise and experience at the regional level and forming partnerships with nearby institutions. Such networks then link nationally and internationally.

The changes suggested here are not impossible and indeed are under way already in many institutions, such as in my own university’s Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures. They will lead to a transformation in the mode of operation and the raison d’être of the university itself. Individual staff and students need to feel the magnitude and the urgency of the challenge as well as the moral responsibility to join the quest. This does demand cultural change, perhaps sacrifice and discipline too. But it also presents a massive opportunity for people to grow personally and professionally – and to make a difference.

The question the SDGs pose is: how can we promote human health, prosperity and well-being for all the people of the world and yet live within the planetary boundaries that define the quality of the land, water and air, the finite resources they contain and the balance of nature of which humans are just a part? SDGs are thus not optional extras but critical to the survival of life on Earth.

Peter Horton is research adviser at the Grantham Centre for Sustainable Futures, and emeritus professor of biochemistry at the University of Sheffield.