Brazilian academics have vowed to fight back against threats to academic freedom after campuses were stormed by military police and staff were arrested for their political views in the wake of the presidential election.

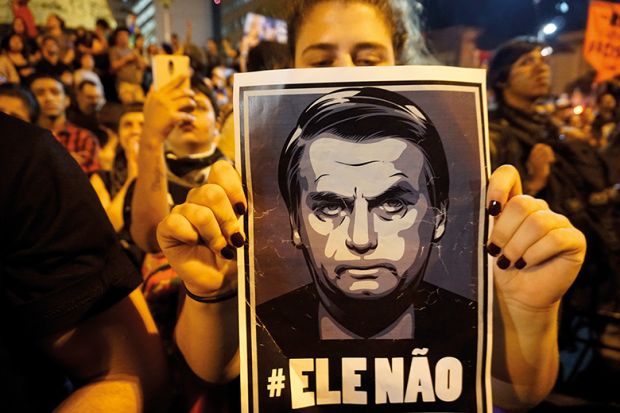

Right-wing candidate Jair Bolsonaro won the presidency with 55.5 per cent of the vote last month, to the dismay of academics who have criticised his failure to commit to tackling Brazil’s research funding crisis and to protect academic freedom.

But fears have deepened in the aftermath of the poll because Mr Bolsonaro’s supporters have pledged to campaign against the “corrupt ideologies” of the academic community.

Academic leaders told Times Higher Education that staff had been threatened and teaching materials had been confiscated by military police with links to Mr Bolsonaro’s political party on the grounds that they contained “leftist propaganda” and “false information” about Brazil’s political history.

“It is a very worrying time for us, and many look back to life under military dictatorship [between 1964 and 1985],” said one university dean, who asked not to be named.

Meanwhile, an anonymous phone line has been set up for students and members of the public to denounce “ideological professors and indoctrinators” in universities.

The initiative was led by Ana Caroline Campagnolo, an elected state representative in Santa Caterina, who asked students to film their classes to catch out “political-partisan or ideological” behaviour from teachers. “We guarantee the anonymity of the denouncers,” she said in a video published on social media.

Adriana Marotti de Mello, professor of business at the University of São Paulo, reported that students in Para State University had already “denounced teachers…because they were discussing ‘fake news’ in class”. “It was enough for police invasion and prison. I cannot imagine what is going to happen [in the future],” she said.

Justin Axel-Berg, associate researcher in higher education policy at the University of São Paulo, described the move as a “direct and first-day attempt to create a climate of fear and persecution” but noted that Ms Campagnolo had since been reprimanded by Brazil’s Supreme Electoral Court, which ruled against the restriction of political speech on university campuses on 1 November.

Opponents of Mr Bolsonaro have vowed to “resist and defend” their academic freedom, and a number of protests have taken place since the election across Brazilian cities. But the majority still admit that they are too afraid to speak to the media without the condition of anonymity.

One academic from the State University of Goiás told THE that as many as 27 universities had reported military incursions into their campuses in recent weeks. “Some cases are more ostentatious than others – it is for show, to [scare] us. But the fascist climate is already apparent,” he said. “We will not bow to it. [It is clear] we have wide-ranging support on this.”

While the Social Liberal Party does not take over leadership of the country until 1 January, it is understood that the party has been able to successfully push for the issuing of arrest warrants in cases where universities were alleged to be breaking federal law.

Vahan Agopyan, rector of the University of Sao Paulo, explained that political advertisements of any kind were still banned by law in public buildings. “With this excuse, in some states the police are acting inside the campuses,” he said.

Dr Axel-Berg concluded: “In the weeks before and shortly after the election, it’s fair to say we were terrified. But the atmosphere has since changed to one of solidarity among academics. I don’t believe life will return to how it was in 1964.”