Some of England’s universities have been warned that they are being “overconfident” with their financial forecasts in the light of growing risks associated with Brexit, declining student recruitment and rising pension costs.

The latest report on the financial state of institutions in the country from the Higher Education Funding Council for England paints a picture of an increasing gulf between the haves and the have-nots, with a significant number of universities more exposed to such risks.

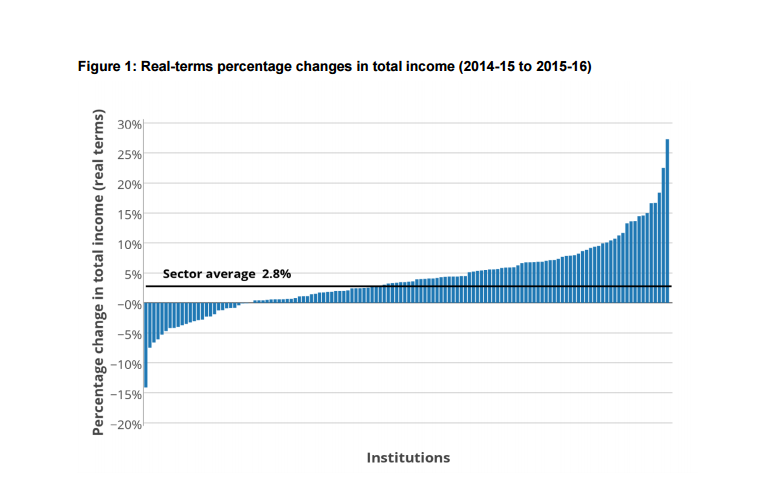

This is most starkly illustrated by data in the report that show that the gap between the lowest and highest surpluses among England’s universities grew by 26 per cent in 2015-16. There was also a wide disparity in the change in total income from the 2014-15 to 2015-16 academic year, with 27 institutions seeing a real-terms fall in money coming in (see chart below).

The mix of fortunes is also illustrated by universities’ surpluses and deficits: overall, the sector reported a surplus of £1.5 billion, or 5.2 per cent of total income. But this ranged from a deficit of 7.2 per cent at one university (individual institutions are not named in the report) to a surplus of 32.1 per cent at another.

Much of the report focuses on student recruitment, given that tuition fees now represent about half of universities’ total income in England.

It reports early data on student numbers for this year showing that although the total number of undergraduate entrants (from all countries) marginally fell by 0.6 per cent, this masks “considerable disparity”, with an average decline of 7 per cent for those 58 institutions where recruitment has fallen. Hefce also points out that early Ucas data show a relatively large decline in applications for next year.

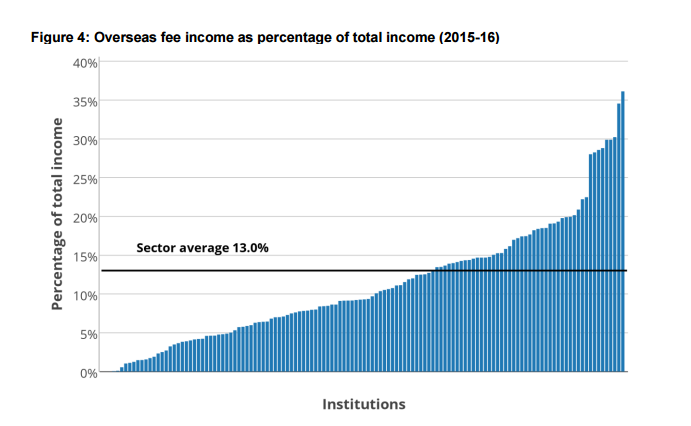

The reliance of universities on fee income from overseas students is also highlighted in the report, with this representing £3.8 billion in total in 2015-16. Hefce warns that universities’ forecasts that this will reach £4.8 billion by 2018-19 may be “difficult to achieve” because of “increasing competition from other countries and proposed changes to student immigration rules”.

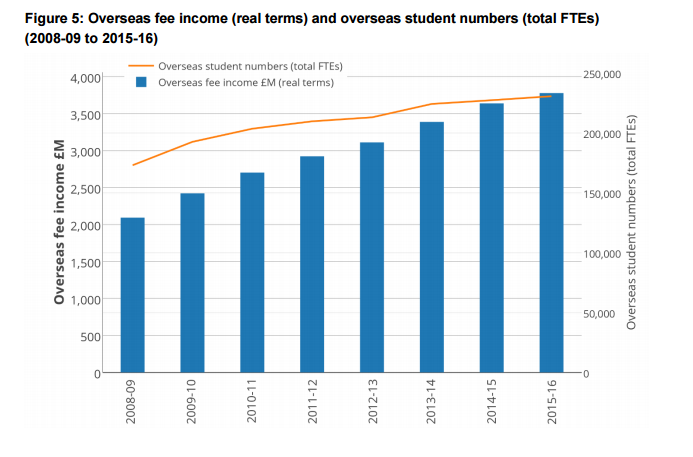

To bolster its point, Hefce’s report displays a chart (see below) that shows that since 2008-09, “although both overseas student numbers and overseas income have increased, the increase in overseas fee income is greater, indicating that the rise in overseas income is largely due to an increase in fees charged. Price sensitivity is a key factor in a competitive global market and there may be a limit to the extent to which fees can be raised further, even with the current weakening in sterling.”

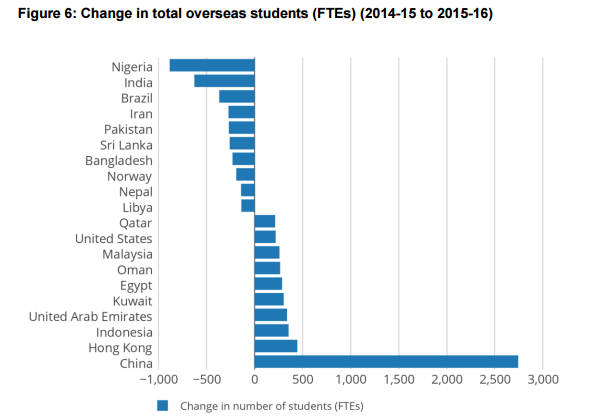

The recent changes in where overseas student fee income comes from are also shown by a graph (see below) that lays out the continuing shift towards China and other countries in East Asia at the expense of places such as South Asia.

Meanwhile, the way financial power is concentrated in a small number of universities in England is clear from figures in the Hefce report on how much wealth institutions have to fall back on (reserves) and capital spending.

Capital investment in 2015-16 was £3.8 billion in total, a rise of 14.5 per cent compared with 2014-15, but this was “driven by a small number of institutions, with 18 contributing 50 per cent of the sector’s capital expenditure. A total of 53 institutions reported a decline in capital expenditure over the period.” On reserves (assets less liabilities, which the report says in broad terms “can be used as a proxy for the overall value of an institution”), just 10 institutions reported half of the sector’s total reserves.

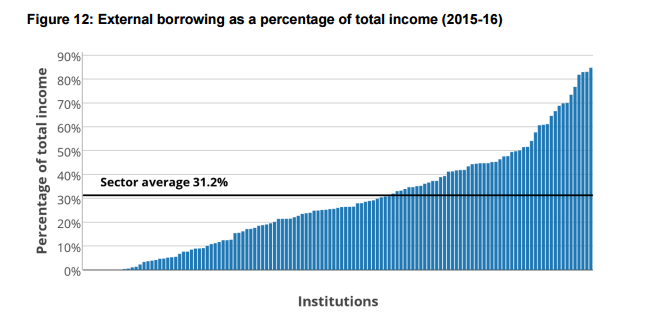

Hefce warns that “without increased surpluses and continued government support, there is a risk that the sector will be unable to maintain the scale of investment required to meet rising student expectations, build capacity for growth and ensure that it can remain internationally competitive”. It also says that the capacity to borrow more may be “limited”. The below graph shows just how much universities in England already borrow.

On pension liabilities, the report also seems pessimistic. These increased by 33.1 per cent over the year to reach £9.5 billion, and they “look set to rise further following outcomes of triennial reviews of two of the sector’s major pension schemes, the Universities Superannuation Scheme and Local Government Pension Schemes”.

In conclusion, the report aims its warnings firmly at the universities that are most at risk from a combination of declining student recruitment, Brexit and rising pension costs, pointedly saying that “we regard the financial projections from some institutions in July 2016 as overconfident”.

Madeleine Atkins, Hefce’s chief executive, said that, across the sector, “we are seeing increasingly greater variation in financial performance”.

“Looking ahead, the sector faces some significant uncertainties and risks that need careful monitoring and mitigation if institutions are to be sustainable in the long term,” she said.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view