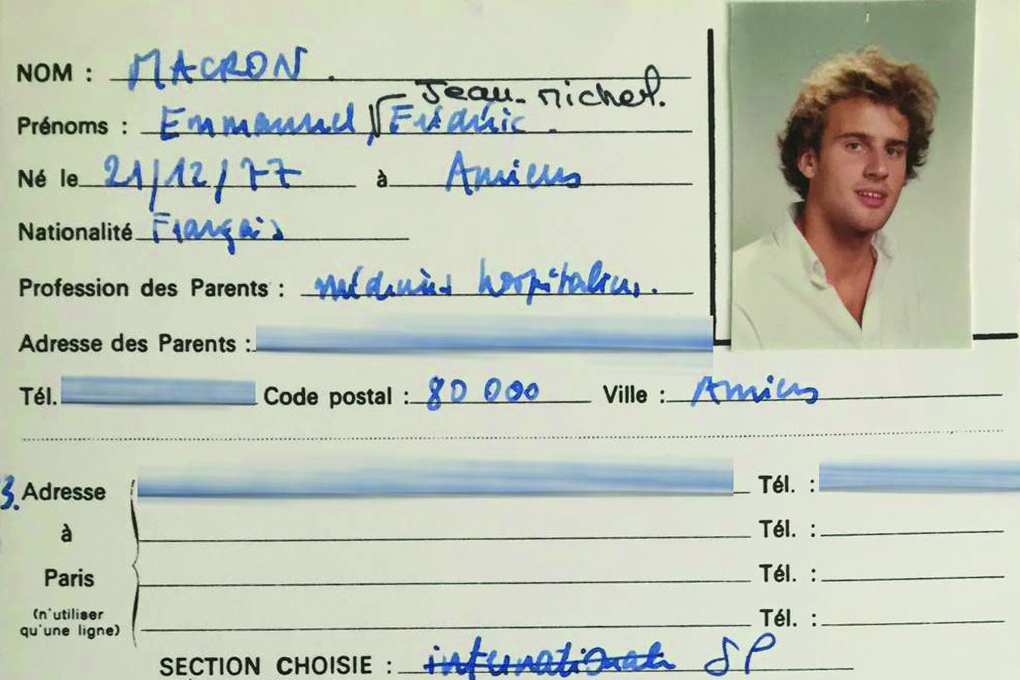

Emmanuel Macron’s rapid rise to France’s presidency was always likely to raise the international profile of his alma mater.

But Frédéric Mion, director of Sciences Po, where the French president was also once a visiting lecturer, was surprised to see a 60 per cent increase in international applications to the elite Paris institution for next year.

“We’ve seen increases of 6 or 7 per cent, even 10 per cent, but never this kind of increase,” said Mr Mion, who has little doubt that the boom in applications is caused by the “Macron effect”, which has led to renewed interest in France from business leaders too.

“This is a direct result of what the world is now feeling towards France – this specific French moment is great for business and a bonus for higher education and I am glad to see Sciences Po was well positioned for that,” Mr Mion told Times Higher Education.

Mr Macron – described by his tutors as an “exceptional student in all respects”, despite his “tendency to be too sure of himself”, according to press reports – has yet to visit Sciences Po since he was elected in May.

But he has been a frequent visitor in recent years; as finance minister, he was guest of honour at the 2015 graduation ceremony, and he returned three times in 2016, including for the send-off for a retiring lecturer who he had befriended.

If the 40-year-old French leader does return towards the end of his five-year presidency, he is likely to find that the elite institution has changed dramatically. By 2022, Sciences Po aims to have moved into its new Hôtel de l’Artillerie campus – a 14,000 square metre former Dominican convent previously occupied by France’s Ministry of the Armed Forces. Once combined with its Rue de l’Université site, it will create a 22,000 square metre campus in Paris’ historic 7th arrondissement, bisected only by the famous Boulevard Saint-Germain.

“We’ve been given a historic opportunity to create a proper urban campus – one that will be comparable to some of the great campuses found in New York, Singapore or Hong Kong,” said Mr Mion.

Sciences Po will not significantly increase its numbers from about 13,000 students – 8,000 of whom are in Paris, with the others based in its network of six regional campuses – but will close 17 sites to consolidate teaching and research in just four locations, he explained.

Search our database for the latest university jobs in France

“We’ve chosen to reaffirm our presence in the city, rather than think about moving to the outskirts,” said Mr Mion – a reference to the decision by some institutions to relocate to Paris-Saclay, a €7.5 billion (£5.9 billion) research cluster south of Paris. “We realise the value of having a central location in a global capital, rather than being in the suburbs.”

This includes easy access to Paris’ business and political elite, with many lawyers, diplomats and entrepreneurs teaching for several hours a week in addition to their normal day job, Mr Mion said.

“If we were so far away, they probably could not play such a role with us because it would be too much effort [to reach students],” he added.

Sciences Po has diverged significantly from other French higher education institutions in several other ways.

While Sciences Po is highly selective – only about one in five undergraduate applicants was accepted last year – about 10 per cent of its intake have, from 2002, been admitted, not on the basis of the notoriously tough prépas entrance exam, but after an interview. This has enabled Sciences Po to admit many more students from deprived areas, with 27 per cent of students now on scholarships. “This was controversial when it was introduced, but it is now part of the landscape,” said Mr Mion.

Like its sister institution, the London School of Economics, which was modelled on Sciences Po when it was founded in 1895, it is also highly international, with about 50 per cent of students coming from abroad. That international fee income has further empowered Sciences Po’s long-held tradition of academic autonomy, allowing it to experiment with new degrees mixing different disciplines, Mr Mion said.

“Only about 38 per cent of our income comes from the state, which is much less than it was for us a few years ago,” he said, comparing it with other French universities, which typically receive 90 to 95 per cent of their funding from the government.

So, will President Macron seek to give other universities a bit more Sciences Po-style freedom to experiment and also expand their international student intake?

“[Macron] is looking for ways to give more freedom to universities. Since he’s come to office, he’s been a game changer for many of us, particularly in the way that France is viewed,” said Mr Mion, whose staff, as a result, are having to sift through many more applications.

“There are space constraints so it is difficult to add to our current population, so it’s a matter of who we will take,” said Mr Mion, who added “it’s a nice problem to have”.