At every stage of her academic career, Sunny Singh has been “pretty much the only woman of colour in my area”. In her 15 years working in UK higher education, the internationally acclaimed author and senior lecturer in creative writing and English literature at London Metropolitan University has been the only ethnic minority woman in her department, bar a couple of temporary members of staff.

While initiatives aimed at widening participation mean that student populations in the UK are much more diverse than they were 20 years ago, there has not been the same level of progress for black and minority ethnic scholars in the academic workforce.

The result, according to Dr Singh, who was born in India, is that the few BAME female scholars in the academy “take on pastoral duties and responsibilities” that go way beyond the requirements of their job.

“We’ve especially got lots of young women of colour now going into higher education…But they’re experiencing internal aggressions and microaggressions, plus all the issues that come with being a student,” she said. “So who do they come to when they have problems? The one person who kind of looks like them.”

The dearth of ethnic minority women in academia means that Dr Singh even supports students who are not at her institution.

“I’ve had multiple conversations in the past week with students at other universities who either email me or DM [direct message] me on Twitter saying: ‘We know you’re a visible woman of colour in higher education, can we talk?’ Yes, it’s not ‘my job’. I’m not paid for it. But if I am one of the few people they can go to in this industry, I can’t say: ‘No, sorry, it’s 5pm.’ You’re there,” she said.

“I don’t teach at Oxford, and I don’t teach kids who are walking in with everything sorted for them. My students need every last bit of our work. But unless the [institutional] structures, unless the industry can understand what I do, which it doesn’t, I will be penalised.”

Dr Singh is not alone. Research from across the world suggests that female ethnic minority academics routinely face additional challenges that other colleagues do not and also take on extra labour, often without recognition – a burden that can have a detrimental impact on their career progression and their mental health.

A 2019 report released by the University and College Union, drawing on interviews with 20 black female professors in the UK, found that these scholars faced a culture of “passive bullying and racial microaggressions” that narrowed their chances of promotion.

A mixed-race associate professor in the UK, who wished to remain anonymous, said she was often asked by her university to speak on panels or to participate in diversity initiatives because of her ethnic background, but such work was not rewarded.

“You don’t get any credit for it in any way. It’s not remunerated. You don’t get a lower workload. You don’t get any points. It’s considered ‘good citizenship’ in the institution,” she said.

Having found herself “overwhelmed with work”, she started to decline such invitations, she went on. However, her manager pushed back, arguing that the additional activities were “really important” and might not be properly addressed without her expertise.

“I felt that, in a way, it was making me feel guilty for something that really is not my responsibility,” she said. “My colleagues of colour at the institution I’m at and elsewhere are constantly telling me these kinds of things. They ask you to be on diversity panels, and if you say ‘no’ they make you feel guilty and [tell you such efforts are needed or] change won’t happen. [Yet] if you are on those panels, it doesn’t get recognised.”

The academic explained that an additional burden is that “part of surviving as a person of colour in these predominantly white spaces is building solidarity networks” of colleagues who will “stick up for you or point issues out”. However, it “takes a long time to do that”, and it is “hard to then be selfishly oriented towards doing your research, which is what you actually get promoted on primarily”, she added.

“Everyone of colour that I know in academia is just totally exhausted…There’s a real culture of exploitation, I think, in terms of emotional commitment to the institution and its promise of progress.”

A south Asian academic, who also asked not to be named, said BAME academics tend not to be put forward as PhD supervisors by managers, which makes it difficult for these scholars to be promoted.

“Exclusions are probably made in ‘good faith’. But if your expertise is completely disregarded and even the supervisions you have expertise in are handed over to white colleagues who don’t speak up, that is another form of exclusion and impacts your career,” she said.

“It’s also an accumulative process. When you have students who see that the academic’s own colleagues in the department are dismissive of their qualifications and expertise, why should they take you seriously?”

A black British scholar who resigned from her university last year over her treatment by managers said she had taken on additional duties to help the institution tackle the BAME attainment or awarding gap, but the tasks had not been properly accounted for in her work plan. She was “the only female academic of colour and also the only Muslim academic” in her department.

“I was also on a lower [pay] grade than colleagues with less qualifications and experience than I had, even though I was carrying out significant leadership responsibilities. When I asked when I would be ready for a regrade in terms of progression, the goalposts kept moving. I was told I had to be here for two years, and then for three years and then for four years,” she said.

She said she had been interviewed for “a secondment with a focus on the awarding gap”, and had been told that she was “by far the best candidate”. However, the university then announced that the role was no longer available.

“I was contacted a couple of days after, asking whether I would be interested in doing some research staying at the same grade I am at but doing work that was in the role that was originally advertised,” the academic said.

“Because research is required in terms of progression, I accepted that…[But] my head of department actively blocked me from taking the research opportunity, saying they couldn’t afford for me to be moved out of teaching. It was not the first time that my head of department had actively blocked me from taking on research responsibilities. There was a really significant glass ceiling that was placed and was preventing me from progressing.”

The scholar said the majority of BAME female academics she has spoken to have “either left academia because of toxic working environments or moved institutions…because they found they weren’t able to progress where they were based”.

“It’s academics at all levels – early career academics who are leaving academia all the way through to black female professors who have really worked hard to navigate their way through but are now seeing that even as professors they’re encountering the same level of prejudice,” she added.

Dr Singh observed that for ethnic minority scholars, even the decision of whether to leave an institution or quit academia altogether carries extra considerations that weigh on their conscience.

“If I walk away, that’s one fewer woman of colour on faculty. That is one fewer person [students] can see…So it’s not just a professional dilemma. For me, it’s a moral dilemma. That adds to the labour,” she said.

The only way Dr Singh sees this changing is if universities recruit more BAME faculty.

“Hire a wider group of people, pay us equally, promote us so that we stay on rather than leave because we burn out, and empower us to make the changes that the industry needs. That’s the starting point,” she said.

“Beyond that, I think the sector needs a real reckoning over what we want our universities to do…If it is to serve the elite, then any diversity initiative is basically eyewash.”

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

In numbers

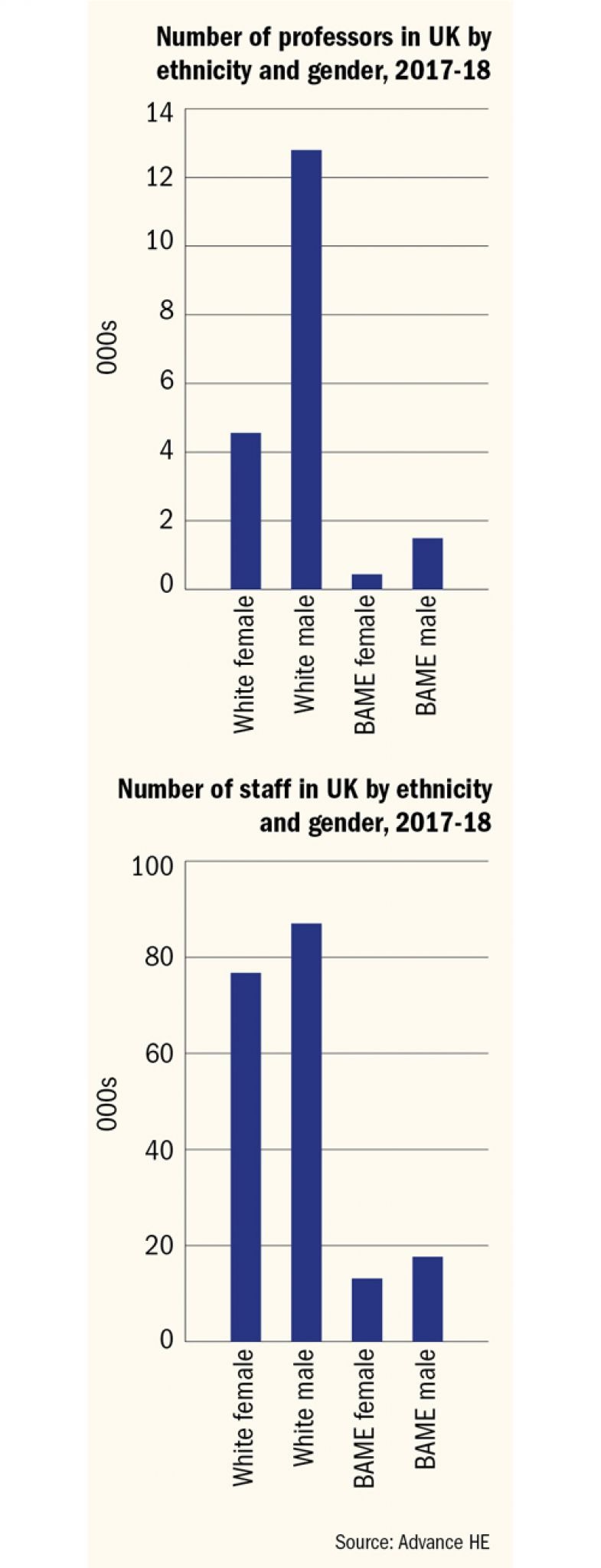

Despite small advances in recent years, the academic workforce in the UK is still overwhelmingly white – and, at senior levels, male. Just 2.3 per cent of professors are BAME women, according to the latest figures from Advance HE (based on the 2017-18 academic year), while 7.7 per cent are BAME men, and 23.6 per cent are white women. Two-thirds (66.3 per cent) are white men.

Ethnic minority academics are even less represented at the senior management level. Just 1.5 per cent of senior managers at UK universities are BAME women, while 3.6 per cent are BAME men.

Overall, BAME women make up 6.8 per cent of all staff at UK universities.

后记

Print headline: BAME women bear extra burdens