When their tuition fees almost triple next year, English students are expected to begin a mass scramble in search of the best-value degree.

As they are unlikely to stop at England's borders, the Scottish and Welsh devolved governments plan to raise their fees to stop students from the rest of the UK scaling Hadrian's Wall and pouring across Offa's Dyke in search of a cheap education. Northern Ireland has yet to make a decision, but already it is clear that there will be a bewildering range of fees across the UK (see table, below).

Although it is impossible to say how everything will play out, observers are already highlighting some likely consequences. These include: confusion for students; less diversity on campus; a fall in the number of English students studying in Scotland and a collapse in the numbers going the other way; a threat to the teaching grant for Welsh institutions - and even more turmoil for universities already reeling from the pace of change.

The devolved administrations must somehow square a huge cut in their higher education budgets with strong political opposition to raising fees. Scottish universities are suffering a 10 per cent cut in their teaching grant for 2011-12, but no party will even contemplate introducing any tuition fees to compensate except the Scottish Conservatives.

According to a report published in February by the Scottish government and Universities Scotland, if universities in England had set their 2012-13 fees at an average of £8,000 a year, Scottish universities would face an annual teaching funding gap of £263 million by 2014-15 compared with their counterparts south of the border. Given that the average fee announced by English universities (before fee waivers) has turned out to be £393 higher than the £8,000 on which those figures were based, the gap could be even wider.

To minimise this disparity and prevent a flood of "fee refugees" from England drowning Scottish universities, Michael Russell, Scotland's education secretary, announced in late June plans to allow his country's institutions to charge up to £9,000 a year for students from the rest of the UK, although Scottish students will still pay nothing. Depending on whether student numbers go up or down, and on what fees Scottish institutions decide to set in September, this could bring in anything between £41 million and £74 million a year by 2014-15, plugging at least some of the funding gap.

In Wales, the situation is even more complex. Welsh universities, like English ones, can now charge fees of up to £9,000, and have plumped for an average fee of £8,800 a year. However, the Cardiff administration will shield Welsh students in Wales from the fee rises: they will have to pay only £3,465 a year, with the government topping up the rest.

So far, so similar to Scotland. But the Cardiff administration will also subsidise Welsh students so that they will pay only £3,465 a year if they study elsewhere in the UK. This is in contrast to Scottish students, who will have to pay up to £9,000 if they attend an institution south of the border.

As in Wales and Scotland, fees will not rise in Northern Ireland for local students, according to the first and deputy first ministers. But there is still no decision on whether the devolved administration's two universities will be able to charge more for students from the rest of the UK.

Northern Irish students who want to study at institutions in England, Scotland or Wales face fees of up to £9,000. This week, the Northern Irish government said such students would be "expected to pay the fee that is set by the relevant university". However, the Northern Ireland branch of the National Union of Students-Union of Students in Ireland is lobbying for Stormont to subsidise students from the province who choose to study elsewhere in the UK.

Adding to the sense of confusion and, for some, injustice and unfair treatment is the European Union rule that means that each country in the UK must charge students from an EU member state the same as local ones. An English student from Newcastle travelling 100 miles to study in Edinburgh could be charged £9,000 a year, whereas a Romanian student who has flown 14 times that distance will be charged the same as a Scot - that is, nothing.

This week, it emerged that the human rights lawyer Phil Shiner plans a legal challenge. He claims that Scotland's policy of charging students from other parts of the UK to study north of the border breaches the European Convention on Human Rights.

For students, the immediate problem is the lack of clarity. "It will become increasingly confusing for people trying to work out what applies when and where," says Liam Burns, president of the National Union of Students. English students mulling over Scottish universities this summer will not learn exactly what each university will charge until late September.

Over the longer term, expect to hear fewer regional accents on campus. "The incentive will be there to stay in your country of domicile," says Burns, adding that this will accelerate a 20-year trend for students increasingly to study where they live. "People should be able to study where it is best for them. If anyone is put off a particular course on the basis of cost, then something's gone wrong," he argues.

Could the vastly different prices even stir resentment between British students on campus? Burns is not convinced it will. "It's not the Scottish students who have done this, it is about what the respective governments have done." The English pay more in Scotland at the moment, with seemingly little resentment, but the gap is set to grow to a whole new level.

Scotland

The overall impact of the fee changes will be to pen UK students into their own home countries. But the flows between Scotland and the rest of the UK could be hit particularly badly.

For Scottish students, the choice between paying nothing to study north of the border and paying up to £9,000 a year if they venture elsewhere means that the stream leaving Scotland could all but dry up. English institutions will remain relatively unaffected - only a few music colleges in England rely on Scottish students for more than 5 per cent of their intake. Even at the northern English universities of Cumbria and Newcastle, no more than 5 per cent of students are Scottish.

The omens for Scottish universities' cross-border intake are much worse, however. Many institutions rely heavily on non-Scottish students (see related file, right), and English students are deserting them even before fees are raised. The number of applications from English students to study north of the border in 2011-12 fell by 14.9 per cent compared with the previous year, to 26,784, according to the Universities and Colleges Admissions Service. The University of Edinburgh alone has reported a hefty drop of 35.6 per cent in the number of applicants from the rest of the UK.

A spokeswoman for Universities Scotland attributes the slump in interest from English students to a combination of factors: a reluctance to leave home during an economic downturn; uncertainty over how much Scottish institutions will charge; and a rush to apply to English institutions in the final year of £3,375 fees. "The priority for English students will be costs," she says. The drop has occurred this year even though English students currently pay just £1,820 a year in Scotland, as opposed to £3,375 a year in England.

If all Scottish universities decide to charge students from the rest of the UK the full £9,000 a year, then "you can predict a fairly big drop in applications", the spokeswoman says. This does not necessarily mean that the number of English students enrolled will actually fall, because Scottish universities are still oversubscribed, she says, but if it does "translate to a drop in students in lecture halls, then that will be of concern". In addition, Scotland's four-year degrees mean that tuition fees could be even more off-putting because total costs for a course could reach as much as £36,000, compared with £,000 in England. Russell, Scotland's education secretary, has predicted that Scottish universities will be restrained, however, and that they will charge an average fee to rest-of-UK students of £6,375.

For the Scottish academy, a drop in traffic from the rest of the UK might not cause great damage to overall enrolments because Scottish universities are likely to soak up large numbers of Scots who reject the much higher fees in the other three countries. However, some institutions do rely heavily on students from the rest of the UK. Four universities - Edinburgh, St Andrews, Glasgow and Aberdeen - receive 67 per cent of the UK students who go to Scotland to study, according to the Scottish government and Universities Scotland report. Of this cohort, one-third attend Edinburgh, and they made up more than half of St Andrews' intake in 2009-10. With English applications to Edinburgh falling by more than one-third this year, the university has already seen a 14 per cent slide in total applications.

On the other hand, from 2012-13, Scottish universities will be free to recruit as many rest-of-UK students as they like. Because a Scottish student studying a humanities subject currently brings with them £5,065 in teaching grant plus £1,820 in tuition fees paid for by Holyrood (a total of £6,885), an English student paying £9,000 could prove a very attractive prospect to a Scottish university, representing a premium of £2,115. "Where some Scottish universities could stand to see additional benefit will be on the lower-cost subjects such as social sciences," says the Universities Scotland spokeswoman. However, Russell has spoken of an "additional sharing mechanism" to make sure that any extra money brought in by rest-of-UK students is redistributed across all Scottish universities. He has also stated that "there has to be some benefit to each university" taking rest-of-UK students, which means that an incentive to take on more students from outside the UK could remain. How much of an incentive remains unclear.

Wales

The new fees regime should have relatively little effect on the flow of students between Wales and England. This is because English students will pay on average £8,800 a year to study in Wales, and £8,393 in England. Welsh students will pay only £3,465 wherever in the UK they go, backed by the coffers of the devolved government.

"I'm not concerned that new fees will hit England-to-Wales student numbers," says one Welsh higher education policy analyst, who asks not to be named. But there are fears that the Welsh government's commitment to fund Welsh students' fees elsewhere in the UK could leave the Higher Education Funding Council for Wales with far less teaching grant than it anticipated. The Welsh government originally predicted that average fees in England would be £7,000. If that had been the case, it calculated that Welsh teaching budgets would be cut by 40 per cent.

However, with the English average at £8,393, the budget cut is likely to be much higher. "The question is: will the decline in teaching grant be as much as in England?" asks the analyst. "I think it will be significantly over 40 per cent, well over 50 - not far away from 80 per cent."

Only when Welsh students actually begin to apply for entry in 2012 will HEFCW be able to calculate accurately how much it will have to pump into English universities. The Welsh government insists that it is "confident in its costings", but the uncertainty over how much will be left for the teaching grant has already pushed up Welsh fees.

Swansea Metropolitan University is charging between £8,500 and £8,750 a year. David Warner, its vice-chancellor, thinks that Welsh universities have gone for the highest fees possible because they are a certain source of income, unlike the threatened HEFCW teaching grant. "They can't risk there being nothing left in the HEFCW pot," he says.

Could the Welsh government's generosity towards its own students tempt English students to play the system? As one former vice-chancellor, who prefers to remain anonymous, notes, "a lot of English middle-class families have holiday cottages in Wales". The Welsh government says it is the responsibility of local authorities to judge whether applicants have "habitual and normal residence" in Wales. "In practice, that can cover a very wide range of individual circumstances," says the government.

Northern Ireland

The Northern Ireland Executive has not yet decided what universities can charge students from the rest of the UK, and it is not likely to ratify any decision until at least the latter half of September. If this deadline slips, or if it is decided that rest-of-UK students will not be charged higher fees, some within Northern Irish universities privately fear that the administration's two institutions will be hit by many more applicants from Great Britain. The union Unite has warned that this will make "competition keener for university places, with an adverse impact on Northern Ireland students".

But one member of staff at a Northern Ireland university suspects that applications will be pushed up not by students from Great Britain - just 410 students from England crossed into Northern Ireland in 2009-10, according to the Higher Education Statistics Agency - but by a surge in numbers from the EU, specifically the Republic of Ireland. "We've experienced increased applications from the republic because there's uncertainty there over the economy," the staff member says. Students from the republic cannot legally be charged more than those in Northern Ireland, where fees will be frozen.

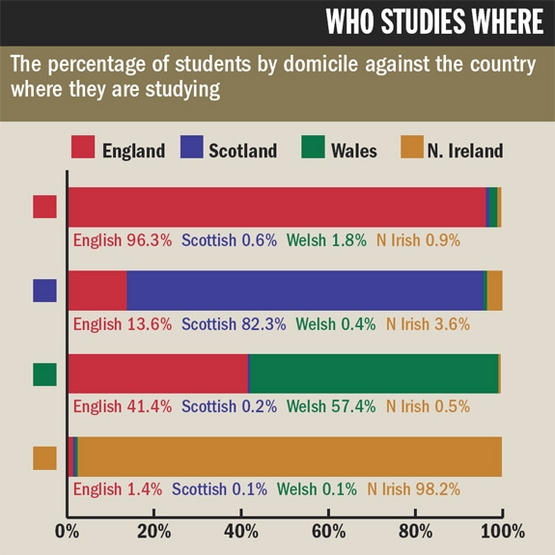

Unless the executive agrees to subsidise Northern Irish students studying in the rest of the UK - and the Northern Ireland Department for Employment and Learning said this week that this was "very unlikely", given the costs involved - they are likely to be deterred from leaving the country. This means the "safety valve is being cut off", and applications from local students will swell, they say. The result will be "increased competition, higher grades and a possibility that Northern Irish students will be crowded out, especially widening-access students". This could exacerbate long-standing concerns over an "undersupply" of higher education in Northern Ireland. In 2009-10, 30 per cent of Northern Irish undergraduates studying in the UK left the province. Yet the administration's institutions are still filled with home students - 98.2 per cent of undergraduates are Northern Irish.

The end of a tradition

Because higher education is a devolved issue, the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills has done no research into how changes in England may affect universities in the rest of the UK. "There's been no systematic attempt to coordinate anything by the policymakers," says Bob Osborne, a retired professor of public policy at the University of Ulster. "Each country has done its own thing."

Discussing different tuition fees across the UK in his report in July on access to higher education, the Liberal Democrat MP Simon Hughes wrote of the "foreseen and potentially unforeseen consequences of these decisions for the cross-border flow of students". There had "long been a tradition of people living in one of the four home countries and then going to university in another", he wrote, noting that he was part of the tradition, as someone who spent part of his childhood in Wales and studied at the University of Cambridge. When British students take up their places at university in 2012, however, it is a tradition that is likely to be on the wane.