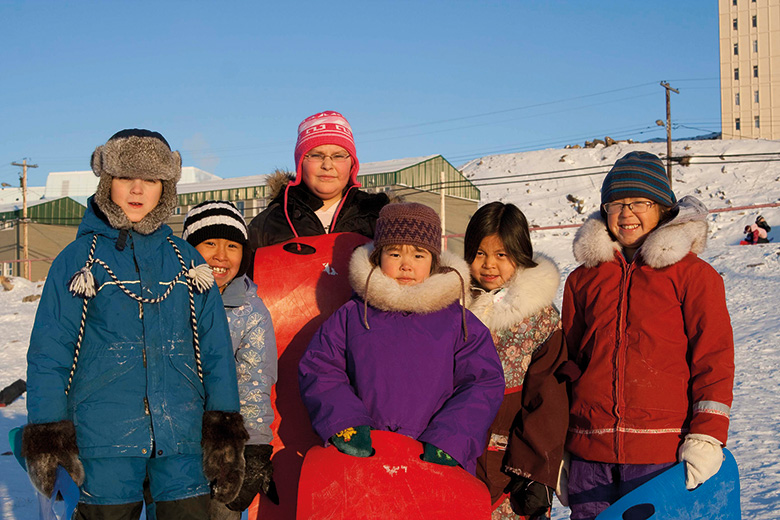

Walking across the Arctic tundra in Iqaluit, on Canada’s Baffin Island, it is not hard to appreciate that this is one of the most remote regions of the world.

Leaving behind the brightly coloured houses on stilts that make up most of the capital city of Nunavut, Canada’s northernmost territory, the only life to be found on the rocky outcrops overlooking Frobisher Bay is the dark blue berries underfoot. Just inland is the Arctic Survival Store, which sells knives, guns, furs, fishing equipment and outdoor clothing for the town’s 7,700 inhabitants, most of whom work for the federal or territorial government, or in mining or fishing. Indeed, Iqaluit means “place of fish” in the local language of Inuktitut.

But while the sea’s bounty may be easy to come by, fruit and vegetables are much more scarce – and many basic provisions are very expensive: a bag of flour sets you back nearly C$15 (£9). Iqaluit, like the rest of Nunavut, has no road, rail or marine connections for part of the year to the rest of Canada, so everything has to be flown in. Passengers share the northbound planes with such supplies, but the three-hour flight from Ottawa costs about C$1,500, so few people from the rest of the country have ever visited.

Nunavut Arctic College is the territory’s only post-secondary institution, but it has five campuses, one of which is in Iqaluit. It also has 25 community learning centres: one for each of the indigenous communities in the region. It offers just three degree-level programmes, all of which were developed in partnerships with universities further south: “Arctic nursing”, teacher education and – the most recent addition – law.

Last year, the Canadian and Nunavut governments announced a C$30 million joint investment in programmes such as Inuktitut interpretation and translation, and there are hopes that the college will gain university status within five years.

Aboriginal people are the fastest-growing demographic in Canada. More than 1.6 million people – or 4.9 per cent of the country’s total population – self-identify as indigenous, according to the 2016 National Household Survey, representing a 42.5 per cent increase since 2006. And, according to John MacDonald, Nunavut’s assistant deputy minister of education, interest in them is increasing nationwide.

“We have been inundated with requests from schools [further south] for exchange trips with our students,” he says.

One reason relates to the publication of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s final report in 2015. Established in 2008, the commission was one of the means by which the government sought to atone for the Indian residential schools system, which operated from the 1870s until 1996 and enrolled 150,000 aboriginal children. After the system’s closure, thousands of former students alleged that they had been subjected to physical, psychological and sexual abuse. The commission concluded that the system was established for the purpose of separating children from their families in order to minimise the families’ ability to pass on their cultural heritage.

The report published 94 “calls to action” to “redress the legacy of residential schools and advance the process of Canadian reconciliation”. Ten of these relate specifically to education. One calls for the elimination of educational and employment gaps between aboriginal and non-aboriginal Canadians; according to Universities Canada, just 9.8 per cent of the former have a university degree, compared with 28 per cent of the latter. Another calls for legislation requiring the development of “culturally appropriate curricula” and the protection of aboriginal language courses as credit courses. A third asks post-secondary institutions to “create…degree and diploma programmes in Aboriginal languages”, while another calls for provincial governments to provide universities with the necessary funding to “educate teachers on how to integrate indigenous knowledge and teaching methods into classrooms”. Senior-level positions dedicated to aboriginal course content are also advocated.

The report is already resulting in a big shift in the way Canadian universities operate. Several institutions now have senior administrators dedicated to indigenous education and research. Some have introduced or expanded aboriginal student centres and appointed elders-in-residence as custodians of indigenous knowledge. And there is a concerted effort to widen higher education access to the three recognised groups of indigenous people: First Nations, Inuit and Metis.

Many Canadian universities have also begun to acknowledge that they are situated on the traditional lands of certain indigenous groups, and some are renaming buildings and erecting statues to celebrate famous aboriginal figures.

On the teaching side, institutions are incorporating indigenous knowledge into the curriculum. Last year, two universities – Lakehead University in Ontario and the University of Winnipeg in Manitoba – made indigenous learning part of degree requirements for all undergraduates. There is increasing competition to hire indigenous scholars, and research papers relating to indigenous studies in disciplines ranging from history to mathematics are becoming much more common.

A Universities Canada survey published in June found that more than two-thirds of its 96 member institutions are working to include indigenous representation within their governance or leadership structures. Close to 80 per cent have made “important commemorative or symbolic gestures” to acknowledge indigenous people, residential schools or reconciliation; and just under 70 per cent are developing strategic plans for advancing reconciliation.

“Indigenous studies as an academic area is exploding,” says Kevin Lamoureux, associate vice-president of indigenous affairs at the University of Winnipeg. “We used to see [indigenous studies] as an anthropological exercise, looking at indigenous people prior to contact,” he says. “But now it is much more than that. It incorporates how indigenous people contributed to modern inventions. The indigenous side of every discipline is researched. We’re a richer community because of this. Up and down the university campus, people are recognising that.”

Winnipeg is home to Canada’s largest urban indigenous population – roughly 78,000 people, according to the 2011 National Household Survey. So it is no surprise that its university has one of the highest rates of aboriginal enrolments, with 13 per cent of undergraduates self-identifying as such. The institution also offers master’s degrees in indigenous governance and indigenous development.

Lakehead also has aboriginal programmes, including a bachelor’s in aboriginal education and a native access programme, intended for students of aboriginal ancestry who have not yet met the institution’s entry requirements. Its aboriginal mentorship programme, which recently received a C$1 million donation from the family foundation of a local entrepreneur, worked with more than 2,750 indigenous high school students from northwestern Ontario in 2016‑17, up from just 40 when it began in 2013.

The institution also recently inaugurated a “telepresence room”, which uses state-of-the-art technology to host videoconferences with students and staff at its second campus in Orillia, 1,000km away. Brian Stevenson, president of the institution, hopes that improvements in broadband coverage in the northern territories will eventually make it possible for indigenous students in those regions to use this technology to save costs by completing the first year of their degrees at home.

“We are the only university in Northern Ontario, an area slightly smaller than the size of France,” Stevenson says. “We have a mandate to connect to that remote region and provide full academic services to it.”

One student to benefit from all this activity is 41-year-old Charlene Hallett, who is now in her third year of study at the University of Manitoba.

“I grew up so poor I don’t think I ever saw university in my future,” she says. But when the youngest of her three children began school, she decided that she “wanted to go back to full-time school, too”. So she enrolled on Manitoba’s free access programme, which provides academic, personal and financial support to aboriginal people, local residents and those on low incomes.

The institution has elders-in-residence to provide cultural and spiritual guidance to indigenous students and staff. It also has a site for “smudging”: an aboriginal tradition involving the burning of sweetgrass, sage or cedar. For Hallett, it is “a home away from home: I have received teachings that are reflective of my culture. That adds to my ability to be successful as a student.”

Richard Hill is senior project coordinator at the Indigenous Knowledge Centre at Ontario’s Six Nations Polytechnic, which is owned and run by indigenous people. He says that mainstream universities must work with aboriginal communities when devising their indigenisation strategies.

“We have a phrase – ‘nothing about us without us,’” he says. “It means that if you’re going to talk about our culture, you have to engage with us. History books don’t [tell] our story; when I was young, it was taught [that] there were no living descendants of natives, and that our culture had died. The most effective learning is when [teachers] engage with us in the classroom. It is important for young non-indigenous people to meet indigenous people and see what they look like.”

But attracting indigenous students has its challenges. For starters, the residential schools system has left a legacy of mistrust in education. In addition, finding indigenous people is not always easy. Although increasing numbers of Canadians self-identify as aboriginal, many refrain from declaring their ethnicity on official forms, often because of shame or concerns around their safety.

Noah Wilson, president of the University of Manitoba’s Aboriginal Students Association and a fourth-year student studying aboriginal governance and corporate finance, says that many residential school survivors tell their children not to declare as indigenous, despite the potential financial benefits of doing so, because, for them, their ethnicity “was an inhibitor in terms of career development”.

One of the association’s initiatives aims at increasing awareness of career opportunities for indigenous students. Wilson, a Cree from the Peguis First Nation community north of Winnipeg, says that some students are concerned – groundlessly, in his view – about being hired by companies as “tokens”. “[Actually,] they’re hiring us because we have a certain cultural sensitivity to the fastest-growing demographic in Canada,” he says. However, as humility is one of seven sacred teachings within indigenous communities, aboriginal people can find it difficult to convince recruiters that they have the necessary skills to do a job, he adds.

But perhaps the greatest challenge that young aboriginal people face is the intergenerational trauma and general underprivilege of their backgrounds. Poverty and inadequate housing are still commonplace, and the aboriginal suicide rate is almost double that of non-indigenous Canadians. For Inuit people, it is 10 times higher, according to Statistics Canada.

Brenda Small is vice-president of the Centre for Policy in Aboriginal Learning at Confederation College, in Thunder Bay, Ontario, which specialises in applied arts and technology. She says that as part of their efforts to recover, drug addicts are often advised to enrol in higher education, meaning that in some of the institution’s niche indigenous programmes, more than half of students are withdrawing from opiates.

Indigenous people living on reserves are at a further disadvantage because their funding for education and healthcare comes from the federal government, rather than from the provincial governments that fund everyone else. The result, according to one estimate, is that 30 per cent less funding is available for them.

Aboriginal families who have migrated to large cities – often with the intention of seeking better education – have found themselves subjected to severe racism, abuse and even murder. In Thunder Bay, which has a relatively high concentration of aboriginal people, seven indigenous students died after moving to the city to attend high school between 2000 and 2011. And in July, a 34-year-old Anishinaabe woman was killed in the city’s streets after being struck by a trailer hitch that someone threw at her from a car. Last year, the Canadian government said that the number of missing or murdered indigenous women in Canada since 1980 might be as high as 4,000.

Cynthia Wesley-Esquimaux is chair on truth and reconciliation at Lakehead, which has its main campus in Thunder Bay. She says that some local high schools received less than half the typical number of indigenous pupils in the wake of the murders.

“We want northern communities to send their kids to us. A lot of work needs to be done to make that happen,” she notes.

However, the fact that Lakehead now has more than 1,100 aboriginal alumni “makes a big difference” to its recruitment efforts, she adds.

Angelique EagleWoman, dean of the university’s Bora Laskin Faculty of Law, which specialises in indigenous law in the Northern Ontario region, insists that Thunder Bay is safe for indigenous people. But building “respect for diversity, and intercultural competency and understanding” is still a work in progress. “A lot of indigenous [people] don’t feel respected,” she says. “When you can’t make basic governance decisions [about] how your community should be educated, you’re being put in a role of incompetency. That needs to change.”

Those undertaking research among indigenous communities are obliged to demonstrate sensitivity. Scholars wishing to conduct research in Nunavut, for instance, must first obtain a licence. Mary Ellen Thomas, senior research officer at the Nunavut Research Institute, which administers the licences, says that this is partly so that officials can track scientists in the region for safety reasons. But it also means that research that would have a detrimental environmental or social impact on local communities can be vetoed; it can take a year for all the terms and conditions to be negotiated, she says.

Scientists are not generally taught “how to work on indigenous science”, she explains, and they often start out in the Arctic region with absolutely no interest in it. However, they typically undergo a “process of discovery”, such that “in the third year they often say: ‘I think I’ll bring an elder along on my project’, and, by the fourth year, they say: ‘I don’t know a thing: this elder knows so much more than me.’ But some researchers have been here for 30 years and still have their blinders on.”

Jamal Shirley, manager of research design and policy development at the institute, says that language is one of the main barriers preventing academics from collaborating with Inuit communities on research, particularly given that the majority of indigenous knowledge is passed on orally. Hence, “there is still a lot of learning and bridging that needs to happen for Inuit knowledge to inform research”.

Jim Woodgett, director of research and senior investigator at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute in Toronto, says that at the beginning of the millennium, many conversations about indigenisation related to how Western science could “help aboriginal populations”. But the focus now is on a much more symbiotic relationship.

For him, the most effective way of achieving progress in this area is to tie indigenous inclusion and research to funding. For example, earlier this year, Canada’s funding councils told universities that they would lose out if the demographic profile of their candidates for the Canada Research Chairs programme (in which indigenous people are typically underrepresented) did not reflect the demographics of eligible academics.

But not everyone is in favour of incorporating indigenous knowledge into teaching and research. Woodgett partly blames “pseudoscience, which is very much the creation of Western civilisation”, for the scepticism among academics and the wider community about indigenous knowledge. “It gives natural medicines a bad name,” he says.

Thunder Bay’s Confederation College has seven “indigenous learning outcomes”, one of which requires students to relate principles of indigenous knowledge to their career field. But Small admits that some non-indigenous students question its relevance. “My response is: ‘Do you want to work in the real world? You will encounter indigenous people. We see you as a graduate with value-added ability.’ We say that it’s not so much about native people [as it is] about Canada’s history.”

In an article in Times Higher Education earlier this year, two professors based in Manitoba wrote that “many scholars are afraid to publicly question the indigenisation of knowledge for fear of being labelled neocolonialist or even racist”.

According to Rodney Clifton, professor emeritus of sociology at the University of Manitoba, and Gabor Csperegi, professor of philosophy at the Université de Saint-Boniface in Winnipeg: “Current political thinking in both Canadian wider society and universities holds that indigenous knowledge comes from the elders, whom respectful people…cannot legitimately question. Hence, although indigenous knowledge is so important that it must be taught, it is treated as so sacred that it can’t be openly debated.”

Frances Widdowson, associate professor of political science at Mount Royal University in Calgary, Alberta, is editing a volume on indigenising the university. She agrees that “there’s a lot of behind-the-scenes propagandist activity that’s happening in an attempt to make it very difficult for anyone to criticise indigenisation”. On its website, Mount Royal says that it “commits to recognising and valuing indigenous ways of knowing”, but Widdowson says that there has been no debate at the university about indigenous knowledge and whether it “deserves to be valued”.

“In fact, there’s been a concerted effort to avoid discussing it, and it’s basically been imposed by the administration that this would be a really good thing to do because it would raise the self-esteem of aboriginal people and, therefore, make it easier for them to succeed in university,” she says.

“That is a highly dubious assertion, and I would argue that it’s very condescending. We should include aboriginal people in honest discussions about what constitutes knowledge, not be dictating that we should value whatever it is that an aboriginal person says. What is going to be the educational quality of indigenous students who are not given access to these different critical viewpoints, or [who are not] able to make up their own minds about what they think is valid? They’re going to be spoon-fed dubious viewpoints because that’s felt to be consistent with their culture.”

For Widdowson, much of what is included under “indigenous knowledge” actually reflects the traditional spiritual beliefs of aboriginal peoples. “People are entitled to [these], but we’re not going to Christianise the university, or Islamicise the university or Buddhicise the university. That would be seen as a huge affront to critical thinking and the ability to be free from religion,” she says.

But, she says, colleagues at her institution have been “defaming” her on social media and denouncing her as a colonialist and a racist for expressing such views. And she adds that very few academics publicly criticise indigenisation given that such activities are now being linked to funding. In March, for instance, the Canadian government announced that it would provide C$695,000 for 28 research projects on the experiences of First Nations, Inuit and Metis people through one of the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council’s grants programmes.

“People who are in favour of indigenisation stand to gain a lot in terms of positions and prestige at the university, so a lot of this is a conflict around resource allocation,” she says.

But Winnipeg’s Lamoureux says that Canada “missed out on a whole world of understanding” when it exploited indigenous people, and universities must now “give up privilege to make room for other voices”.

“Science is a way of knowing and trying to understand the world. Indigenous epistemology is just a different method,” he says. “It is so cold here, but indigenous people thrived – they were happy, they had food. So we are speaking [about] a very good indigenous science.”

Ry Moran is director of the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, established in 2015 as the permanent home for all the documents gathered by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He agrees that universities are “critically important” in Canada’s process of reconciliation, in part because, for a long time, they were among the few places that had “real, accurate historical information on what was happening” to indigenous people.

“Universities have been a bastion for honest conversations about who we’ve been and how we’ve been. They’ve also been bastions of advancing indigenous thoughts and advancing indigenous ideas,” he says.

However, even universities have had to undergo a “transition” to help restore trust with indigenous peoples.

“There are ever-increasing numbers of indigenous students coming into [higher education] and finding that it is a positive, enriching and powerful experience. We can contrast that with when it wasn’t,” he says. “Once upon a time, when a First Nations person wanted to come to a university, they had to give up their status of being a First Nations person.”

Lamoureux adds that universities must recognise that “academia has been complicit in the act of colonisation and in the exercise of marginalising indigenous people”.

“We’ve robbed their graves to analyse their skulls,” he says. “We have taken indigenous stories and misrepresented them; we have defined them as we see fit. Part of [establishing] the truth is recognising that…even though universities didn’t create the problem, we inherit the wreckage.”

Strategic advance: Australia steps up efforts but much work remains

Indigenous people in Australia make up 2.7 per cent of the country’s working-age population but only 1.6 per cent of domestic university students.

That is up from 1.2 per cent a decade ago, but Australia’s 39 universities do not consider it sufficient, and they hope that their first sector-wide indigenous strategy, launched in March, will see the growth rate in indigenous enrolments rise by 50 per cent above the growth rate for non‑indigenous students.

Developed in partnership with the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Higher Education Consortium, the initiative also sets a target of equal retention and completion rates for indigenous and non-indigenous students in the same fields of study over the next decade.

The institutions have committed to having indigenous research strategies in place by 2018, and to ensuring that all students engage with indigenous cultural content as “integral parts of their course” by 2020.

Belinda Robinson, chief executive of Universities Australia, says that there is a “really significant amount of exciting research being done in Australian universities at the intersections of indigenous and Western knowledge and scholarship. There’s a whole new generation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander scholars who are leading that work.”

She believes that it is important “not just for Australia but for the world to have that insight about the sophisticated knowledge systems and ingenuity of our country’s first peoples and cultures, [which are] the oldest living cultures on the planet”.

The University of Melbourne has also set itself the goal of getting its proportion of indigenous staff and students to reflect the proportion of indigenous people in the general population – 3 per cent – by 2050. Currently, only 1.2 per cent of staff and 0.87 per cent of domestic students are aboriginal.

Shaun Ewen, pro vice-chancellor (indigenous) at the university, says that several Melbourne research centres are working with and learning from indigenous communities. Its Grimwade Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation, for example, works with Aboriginal artists to apply their knowledge to the preservation of cultural materials. And the Research Unit for Indigenous Languages worked with Aboriginal communities to build an app that collects indigenous knowledge about birds.

But Jessa Rogers, an Aboriginal assistant professor in teacher education at the University of Canberra, says that there are still “significant troubles in most Australian universities” when it comes to indigenous knowledge and indigenous studies as an interdisciplinary field.

“Many universities continue to employ non-indigenous academics to teach indigenous studies, and many non-indigenous researchers continue to gain grants…through indigenous research schemes, using one or two indigenous researchers as the named project leaders,” she says.

Meanwhile, although most Australian universities claim to be meeting their targets for indigenous staff, the majority of these employees are in professional rather than academic positions, Rogers says. “It remains the case that for most indigenous people, short-term and sessional contracts are the main source of [academic] employment.”

And while universities have “fantastic outreach schemes” aimed at recruiting indigenous undergraduates, enabling such students to complete a master’s degree or a PhD is still a struggle, Rogers adds.

“These challenges are made harder by the whitewashing of the curriculum within universities and a lack of understanding of indigenous research methodology within indigenous studies,” she says. “Many supervisors are ill-prepared to support indigenous postgraduates.”

后记

Print headline: In from the cold