Six months ago, one of Canada’s leading neuroscientists, Robert Brownstone, announced his resignation as director of research in neurosurgery at Dalhousie University, Nova Scotia, citing the Canadian government’s “worrisome” cuts to science funding and its shift towards applied research.

Three months into his new post as chair of neurosurgery at University College London, Brownstone is keen to point out that he also was “pulled” out of Canada by UCL’s “huge strength in neuroscience”. But he reiterates his relief at being able to leave behind “some of the depressing things that were happening” under Canada’s recently departed Conservative government, led by Stephen Harper.

“The previous government was not particularly interested in knowledge,” Brownstone says. “They would use policy to make knowledge rather than use knowledge to make policy. That was their attitude. What worried me was not so much [how it might impact on] anyone at my stage in their career, but [how it would affect] the young generation, who would be discouraged from pursuing a life in research.”

Brownstone’s views were widely shared by Canadian scientists. Indeed, such was the scale of their discontent that science policy even became an issue in the campaign leading up to last October’s federal election. And the Liberal Party of Canada’s pledges to redress the situation are considered to be one factor in its landslide victory, in which it won 184 seats, against the Conservatives’ 99.

Not all scientists were critical of Harper’s government. In 2008, physicist Neil Turok took the opposite journey to Brownstone, leaving the University of Cambridge – where he had worked alongside Stephen Hawking for 11 years – to become director of the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics in Ontario. He said at the time that the “underfunding and deprioritisation of basic science made the UK a difficult environment to work in”. And he stands by his decision, describing Canada as “an amazingly supportive environment for great science”.

“I feel incredibly lucky to have had the opportunity to help create [what Hawking has described as] ‘one of the leading centres in the world in theoretical physics, if not the leading centre’. This would certainly have been impossible in the UK,” Turok says.

But many other scientists in Canada are immensely relieved that the Harper era is over. A common bone of contention was the Harper government’s moves to put a greater emphasis on commercialisation of research. According to Jim Woodgett, director of research at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute at Toronto’s Mount Sinai Hospital (which is affiliated to the University of Toronto), that aspiration was “clearly being enacted in terms of the types of funding programmes they wanted, the creation of a number of commercialisation centres and [the placing of] a lot more emphasis on research that would lead to product development. It was all really at the expense of a lot of basic science.”

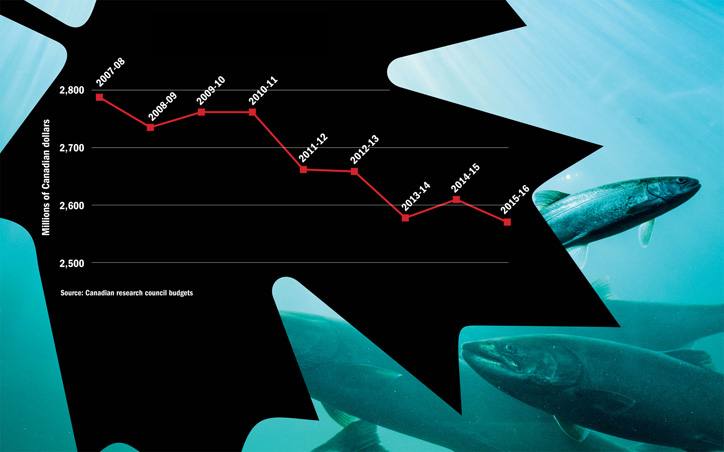

Another gripe was the funding cuts of nearly 8 per cent imposed on Canada’s three research councils, known collectively as the Tri-Council Agencies, between 2007 (the year after the Conservatives came to power) and 2016. And, perhaps most prominently, critics railed against what Woodgett calls the Conservatives’ “command and control” mentality, which required government scientists to apply for permission before speaking to the press.

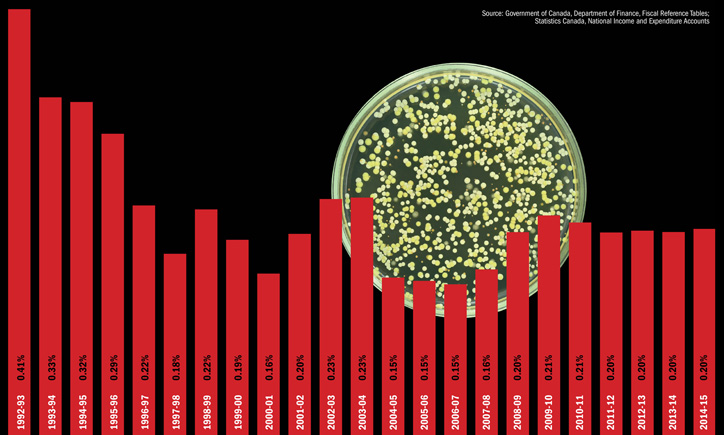

Proportion of Canadian GDP spent on post-secondary education

“Even the [science] ministers’ opinions were not particularly well respected by the prime minister’s office,” Woodgett claims.

In July 2012, this “toxic broth” led to a protest on the streets of Ottawa against the government’s alleged anti-science agenda. Dressed in white lab coats and holding placards reading “no science, no evidence, no truth, no democracy”, the protesters held a mock funeral on Parliament Hill to mourn the “death of evidence” in government.

Two years later, the US-based Union of Concerned Scientists, along with the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada, published an open letter urging Harper to abolish the protocol on speaking to the media. The letter included more than 800 signatures from academics in 32 countries. It also referenced a survey conducted by the institute in 2013, which found that 90 per cent of more than 4,000 federal scientists felt that they could not speak freely about their work.

Michael Halpern, manager of strategy and innovation for the Center for Science and Democracy at the UCS, says it also became very difficult for federal researchers to attend scientific meetings and conferences.

“Travel requests often had to be made up to a year in advance and were only approved days before the conference, if they were approved at all, which was far too late to be able to submit abstracts or present research or sometimes even get a reasonably priced plane ticket,” he says. “Scientists who were trying to stay current in their field, to be able to effectively do their jobs and inform government policymaking, were finding themselves left out of those collaborative spaces.”

Critics were also incandescent about rules imposed by the Department of Fisheries and Oceans reportedly requiring scientific papers written by its researchers to be scrutinised by officials for any “impacts” on departmental policy before they could be published. According to David Robinson, executive director of the Canadian Association of University Teachers, such measures “created some significant data flow problems” for university academics who rely on government data, such as those working in agriculture, environment and climate change.

The Conservative Party of Canada did not respond to an invitation to respond to criticisms of its science policies.

On 4 November, his first day as prime minister, Justin Trudeau restored the minister of science to a Cabinet-level position and gave the job to Kirsty Duncan, adjunct professor of medical geography at the University of Toronto. Her “overarching goal”, she says, “will be to support scientific research and the integration of scientific considerations in our investment and policy choices”. She has been criticised in the media for allegedly promoting an unproven medical treatment for multiple sclerosis, but she insists that her “experience and commitment to science speak for themselves. I have also been and will continue to be an advocate for evidence-based science.”

Meanwhile, the role of minister of the environment was rebranded minister of environment and climate change, reflecting the greater concern about global warming in the new government compared with its predecessor. And a new position of minister of innovation, science and economic development was created, tasked with – as Duncan puts it – “driving the economy” by “working with provinces, territories, municipalities, employers and labour to improve the quality and impact of our programmes that support innovation, scientific research and entrepreneurship”.

Federal research funding

The appointee to that role, financial analyst Navdeep Bains, immediately announced that the government would reinstate the mandatory long-form census, which was scrapped by the Conservatives five years ago – a move lobbied for by academics, who argued that the census provided data that were crucial for university research and government policy. Bains also pledged that “government scientists and experts will be able to speak freely about their work to the media and the public”.

“Openness and transparency in communicating federal science is one of my top priorities,” Duncan says. She also aims to “increase recognition and support for fundamental research” and to fulfil the Liberals’ election pledge to re-establish the role of chief science adviser, which was scrapped seven years ago.

While science funding is a federal matter in Canada, responsibility for higher education lies largely with its 10 provinces. Nevertheless, the Liberal Party has also made several commitments to help to widen access to higher education. These include increasing the value of state-funded bursaries, known as Canada Student Grants, by 50 per cent to C$3,000 (£1,470) a year and increasing the earnings threshold above which graduates must start repaying student loans to C$25,000 a year. It has also pledged to invest C$50 million in additional annual support to the Post-Secondary Student Support Program, which provides additional financial assistance to indigenous students. This is all part of Trudeau’s long-standing goal to see the proportion of Canadians with post-secondary education qualifications rise to 70 per cent, from the current rate of just over 50 per cent.

The new prime minister has also made a commitment to expand the number of positions under the Canada Summer Jobs programme, which provides funding to help employers create summer work opportunities for students, and to invest C$40 million each year to help employers create more work placements for students in science, technology, engineering, mathematics and business programmes.

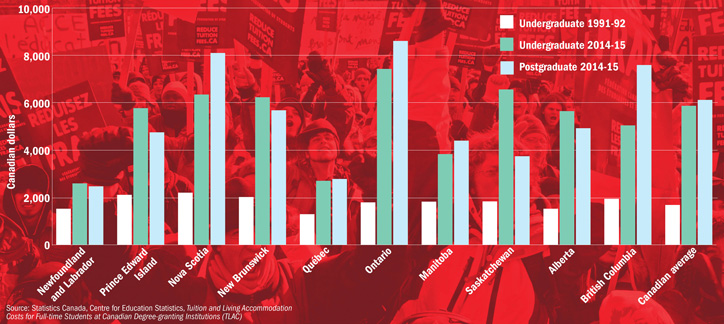

The CAUT’s Robinson would like to see more transparency around how the money allocated to the provinces for post-secondary education is spent – to ensure that it is not redirected to other spending priorities. He adds that one of the “fallouts” of higher education’s being a provincial responsibility is that there is “real inconsistency” in policy across the country. For example, annual tuition fees in Ontario averaged C$7,539 in 2014-15, but this dropped to C$2,743 over the border in Québec, according to Statistics Canada.

Robinson suggests that Trudeau could negotiate national standards for higher education in the same way as is done for standards in healthcare. “There’s a general sense of malaise within the university and college sector right now, where people are feeling like they can’t take any more cuts. There needs to be some federal leadership in recognising that the provinces, in many cases, simply don’t have the fiscal capacity to adequately fund the higher education system that we deserve.”

Michael Bloom, head of the Centre for Skills and Post-Secondary Education at research organisation the Conference Board of Canada, adds that another issue that has arisen from the provincial system is the lack of official recognition of credentials earned in particular Canadian provinces, by both other provinces and other countries.

“We’ve got a study coming out shortly which shows that the annual cost to Canada of non-recognition of credentials…is between C$13.4 billion and C$17 billion, in GDP and forgone earnings. That comes from people either unemployed or underemployed because their credentials aren’t recognised,” he explains.

Tuition fees in Canada by province

However, Bloom says it is “positive” that the Liberals have expressed an interest in more federal-provincial dialogue, which he hopes will speed up the harmonisation of policy.

“Compared with 15 years ago, we have seen some progress, but it’s still in many ways easier to move north-south [to the US] than east-west. Until we get really good mechanisms to collaborate across the country, we’re not going to have the best possible education system.”

One of Trudeau’s main challenges as prime minister will be managing expectations and handling the demands to act instantly on election pledges.

Robinson is hopeful that the reinstatement of the long-form census is “part of a trend towards rebuilding some of the intellectual and scientific infrastructure that has been dismantled over the past 10 years”. But he acknowledges that there is still “a long way to go”. “There were a number of really important social surveys that were eliminated over the years because of programme cuts, and we’re hoping that there will be some reinvestment there,” he says.

“You have to make progress but you also have to recognise that repairing some of the damage that was done, particularly in our sector, is going to take time. I’m not sure if our folks are that patient. There’s a lot of pent-up frustration about the past 10 years that’s now coming to the fore.”

Margrit Eichler, faculty member of sociology and equity studies in education at Toronto, is also wary of being too optimistic. As president of campaign group Our Right to Know, launched during the Conservative government to fight for open access to research results, she has drafted a “huge list” of policies that she would like the new government to implement, which include a guarantee that it will not alter or ignore scientific research for political reasons; a requirement for all research funded by public money to be published; and the placing of more academics, as opposed to industry professionals, in charge of the research councils.

“We want to make sure the councils get their funding increase, that more money is directed to basic research and that the oversight is, in the majority, done by academics. The temptation not to [introduce these policies] will be very strong, as these things cost money, so we need to have a really strong civil society movement to say: ‘We continue to be interested in this and we continue to watch what you are doing,’” Eichler says.

UCS’ Halpern adds that the new government is likely to act first on the pledges “that give them the most political capital and give them the most attention. So the question is will science continue to be a top priority? It’s much easier to fight for transparency and openness when you’re a candidate than when you’re an elected official. So when [a government laboratory] comes out with a finding that is in conflict with the Trudeau government’s policy or priorities, scientists will need to speak up just as loudly [as before] to make sure that that [finding] sees the light of day.”

Woodgett believes that a lot of the optimism about the new government derives from the record of the previous Liberal government, which was in power from 1993 to 2006 and “invested a lot in science and created a number of new science funding programmes”. But he notes that Trudeau “didn’t really make any specific promises” about science funding, and says that one early indication of the depth of the new government’s commitment to science will be whether it supports the Canada First Research Excellence Fund, launched in 2014 by the Conservatives to pump C$1.5 billion into Canadian research at top universities over the next 10 years.

“The honeymoon period is not going to be very long,” Woodgett concludes. “A lot of people voted because they wanted anybody but the previous government. It’s great to be elected on that wave of enthusiasm, but then the expectations are very high and they are inheriting a bunch of problems. I think that in higher education we’re going to have to wait and see.”

Timeline of the Harper government’s ‘War on Science’

February 2006

Stephen Harper becomes Canada’s 22nd prime minister.

January 2008

The department of the environment, known as Environment Canada, orders its scientists to obtain permission from the government before speaking to journalists. Other departments follow suit. The Montreal Gazette later reveals details of a leaked internal document from the department, which shows that the policy reduced its engagement with the media on climate change by 80 per cent.

March 2008

The position of national science adviser to the prime minister is eliminated.

June 2010

The government announces that the formerly mandatory long-form census will become voluntary in 2011.

August 2011

Environment Canada cuts 700 jobs – 11 per cent of its workforce – because of a lack of federal funding.

March 2012

The Canadian Foundation for Climate and Atmospheric Studies, the country’s main funding body for university-based research in this area, closes after the government ceases to provide funding.

April 2012

The government sends media chaperones to shadow Environment Canada scientists at the International Polar Year Conference in Montreal.

The Polar Environment Atmosphere Research Laboratory in Nunavut announces that it will cease full-time operation because of a lack of funding. However, this decision is reversed in May 2013.

June 2012

The government cuts the Department of Fisheries and Oceans’ funding for freshwater research. The department eliminates the Experimental Lakes Area – a freshwater research centre in Ontario staffed by government scientists. The facility is later managed and operated by the International Institute for Sustainable Development, following a national and international outcry.

July 2012

Canadian scientists rally on Parliament Hill in Ottawa for a mock funeral, mourning the “death of evidence” in government. Their main slogan is: “No science, no evidence, no truth, no democracy.”

February 2013

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans introduces a policy that characterises all department research as confidential until it has been reviewed “for any concerns/impacts to DFO policy”, according to the Times Colonist.

March 2013

Canada’s Information Commissioner launches an investigation into the “muzzling” of scientists, following a joint complaint from the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre and the advocacy group Democracy Watch.

May 2013

Canada’s National Research Council launches a new “business approach”, intended to shorten the gap between early stage research and commercialisation.

January 2014

The Department of Fisheries and Oceans closes more than a dozen federal science libraries. Images of dumpsters full of scientific journals and books go viral.

October 2014

The US-based Union of Concerned Scientists and the Professional Institute of the Public Service of Canada write an open letter to Harper, urging him to allow federal researchers to speak freely with journalists.

November 2015

Justin Trudeau becomes Canada’s 23rd prime minister after a landslide election victory for the Liberal Party.

后记

Print headline: Are blue skies back?