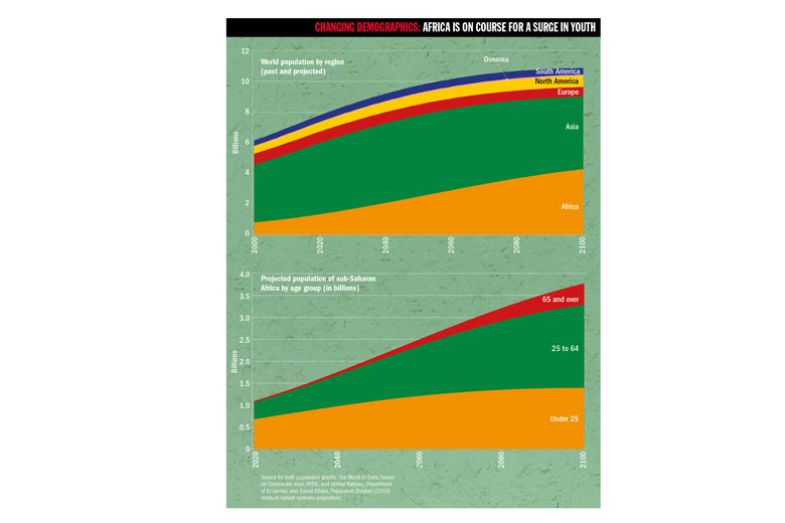

It is no secret that one of the major demographic challenges that will face the world before the turn of the next century is the rapid growth in the population of Africa. At the higher end of projections, the United Nations estimates that the number of people on the continent will grow from about 1.4 billion now to 2.5 billion in 2050 and 4.3 billion by 2100. This will see Africa’s share of the global population rise from less than a fifth now to a full two-fifths.

Those figures are underlain by a surge in Africa’s youth population that is already under way. In sub-Saharan Africa alone, the number of under-25s is expected to rise by 21 per cent to 860 million in just the next 10 years. By 2050, the African youth population is projected to hit 1.1 billion: one in 10 of all people on the planet.

Such figures entail a huge increase in demand for higher education. But even now universities in Africa are barely admitting a trickle from the huge talent pool available to them. The most recent figures from the World Bank show that just under 9 per cent of school-leavers in sub-Saharan Africa currently access tertiary education, compared with the global average of about 35 per cent. In North America, the figure is 84 per cent.

Projections suggest that the volume of young Africans in tertiary education will grow rapidly. For instance, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis estimates that the number of over-15s in most of sub-Saharan Africa who are educated to post-secondary levels will grow from about 30 million in 2020 to more than 90 million by 2050 – with almost 50 million of those in Nigeria alone.

But fulfilling such projections will take a huge effort from governments, colleges and universities to increase capacity. And the population growth figures suggest this will still leave hundreds of millions without access to tertiary education.

In short, the challenge is on a breathtaking scale. And, as Africa Research Institute director Edward Paice warns in his recent book Youthquake, many if not all the other major problems the world faces, from climate change to tackling the next pandemic, are inextricably linked to this rapidly expanding youth population, making improving access to higher education on the continent an absolute necessity for the whole of humanity.

“I don’t think Africa’s development is possible without the development of those young people,” says Adam Habib, director of SOAS University of London and former vice-chancellor of the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, who adds that the whole world will “pay the consequences” if it does not address the issue, given the “instability” that could result from failure.

Pauline Essah, director of research and insight at Education Sub-Saharan Africa (Essa) – a charity dedicated to improving education in the region by working with universities and colleges – agrees that time is not on the world’s side.

“The problem is not going to go away. It is going to get bigger. We are already lagging way behind. You can’t see the same rate of increase of institutions [in Africa] to match the demand, so something has got to give,” she says.

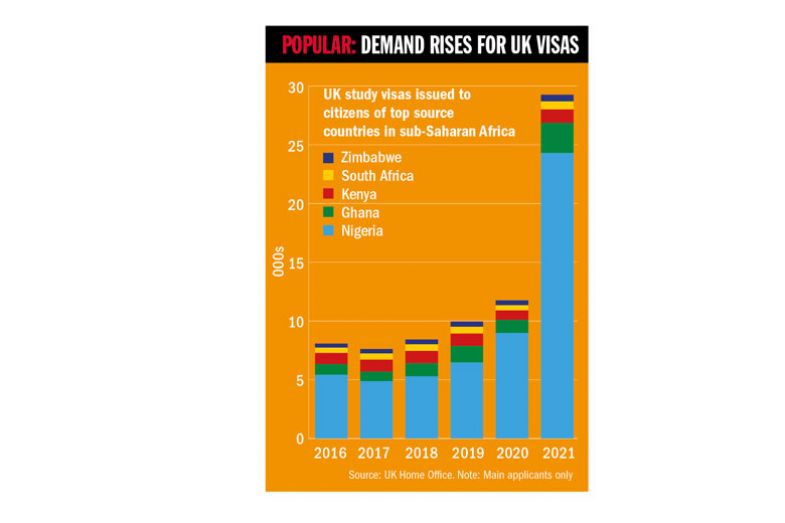

One suggestion is that universities in the Global North could help meet the skyrocketing demand. But those in many developed nations appear to view Africa’s youth surge through only one lens: as another international student recruitment market to be tapped. In the UK, for instance, international fees are usually double, and can be triple, what a domestic student is charged.

One country targeted by the UK’s international education strategy is Nigeria. According to the latest Home Office immigration statistics, Africa’s most populous country accounted for almost 60,000 study visas issued in the year to March 2022 (about 30,000 not including dependants), an incredible six-fold increase from the year before the pandemic and more than half the number issued to the UK’s top two student source countries, India and China. But the number of students gaining UK study visas from other parts of sub-Saharan Africa remains paltry in comparison: just two countries, Ghana and Kenya, saw the number of main applicant visas top 1,000 in the same year.

Habib is scathing about the approach of high-fee countries such as the UK. “Our claim to solidarity [with Africa] is…achieved by taking people and bringing them to the [Global] North and training them. We know that is a scam in the sense that it is a commercial transaction,” he says. “In which moral universe can you claim that you are trying to do solidarity…and charge [African students] three times the fees that you would charge middle-class students in the UK?”

The result, he says, is that Northern universities “end up recruiting, largely, the children of elites”.

Daniel Haydon, professor of population ecology and epidemiology at the University of Glasgow and director of the Glasgow Centre for International Development, says the current approach also prevents universities from nurturing the full range of talent and perspectives that will be necessary to adequately address global challenges.

“The concept that we would charge exorbitant amounts and thereby deter the world’s…brightest talents from conducting the most exciting research with our staff in our institutions is, objectively speaking, a bizarre act of self-harm,” he says.

Of course, universities, organisations and governments in the Global North do offer scholarships and other financial support schemes. But while Essah supports such schemes, she points out that in addressing the affordability issue, they exacerbate another one: brain drain.

“Often, [African students] are coming to study things that are relevant to the Northern institutions. It is very often not focused on the African needs. And often there isn’t any way to connect these students back to their African countries,” she says.

The key for Essah is to find a way for students to maintain links with African institutions. For PhDs, a successful model could be having supervisors from institutions both in the North and South. Strengthened research networks is another benefit of such arrangements, which Essah herself championed when she managed the Cambridge-Africa Programme at her doctoral alma mater, the University of Cambridge.

“It is about sharing knowledge and internationalising the African student’s experience but making sure that they have a route back, so they are not totally uprooted from their local institutions and countries,” she says. When they return, they can still “co-publish papers with their Northern mentors or partners [and] attend conferences”, but to the benefit of future educational and research capacity in Africa.

Such “sustainable collaboration” can lead to “brain recirculation” rather than brain drain, she adds. “We don’t have to feel that Africans have to stay in Africa and not go anywhere…People want to travel, they want to learn…but it is about both sides being able to move around and nobody being exploited in the process.”

Antony Mbithi, a research manager at Essa based in Nairobi, says helping to graduate more PhD students from Africa should be a key goal for institutions in the North that genuinely want to help. He believes that “split-site PhDs” – where students spend a large chunk of their time at an institution in Africa – is “a good model that probably should be more emphasised” as it can direct “resources to many students instead of funding one student in the UK for a long period of time”.

Haydon, too, says the most equitable programmes “may require the student to spend significant periods of time in their home country” as well as “support from a research institution and supervisors in that country”.

“Our experience is that such institutional North-South partnerships confer benefits on both the southern and northern partner institutions, both sets of supervisors, the students themselves, and other students in the southern institution, who are not completely distanced from some of their talented fellow students,” he says.

Jamil Salmi, former tertiary education coordinator for the World Bank and emeritus professor of higher education policy at Chile’s Diego Portales University, is also clear that partnership approaches are vital for the long-term health of higher education in Africa.

“African universities should have a training and staffing plan to identify and plan their capacity-building needs, and future academics could be sent to partner institutions in the Global North as part of the implementation of these plans,” he says.

It may also be useful to stop “the traditional dichotomy between ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’ because of its paternalistic and colonialist overtones”, he adds. “It could be more meaningful to think in terms of forming networks of like-minded universities from all over the world (including Asia and Latin America) interested in supporting the capacity-building efforts of African universities”, along the lines of an organisation such as the Association of Pacific Rim Universities (APRU).

Although a focus on postgraduate education has obvious benefits for increasing capacity in African universities, building the supply of academics for the future, how about the urgent need to expand opportunities below PhD level?

Habib says that even here, it is not helpful for universities in the North to focus on recruitment to their own campuses. “We need to start thinking about doing this on the continent,” he stresses, although acknowledging that “we can’t do it on the continent on the basis of simply the continent’s universities – there’s not enough” and there are “some questions about quality”.

For him, this implies some form of blended learning, whereby students are taught through a mix of in-person teaching in Africa and online content that may have been prepared by partner institutions in the Global North.

Essah agrees that “there are ways in which Northern institutions could contribute to lectures, to designing or developing a curriculum that is based on the local needs”. Her colleague, Laté Lawson, an Essa research manager for data from Togo now based in Germany, says such an arrangement would also help to strengthen links between African institutions and local graduate employers”, rather than furthering a brain drain, because it would be “a kind of sign of quality of a local product. This kind of collaboration…is where I see the future”.

However, there seems to be less agreement about whether universities in the Global North should go so far as to set up branch campuses in Africa.

According to the comprehensive list of international campuses maintained by the Cross-Border Education Research Team (C-BERT) at the State University of New York at Albany and Pennsylvania State University, there are currently only a handful of branch campuses in sub-Saharan Africa set up by institutions from developed university systems, and most of these have narrow focuses, often on business. Even one of the best-known examples, Carnegie Mellon University Africa (CMU-Africa), based in Rwanda, is focused solely on engineering.

Kuyok Abol Kuyok, associate professor of education at the University of Juba, South Sudan, says the proliferation of Western branch campuses in Gulf states suggests that the model does have the potential to be successful in Africa as it “contextualises provision” from high-quality overseas universities. “Also, some relatively rich African countries can afford such universities as a way of addressing the need” for higher education, he adds.

However, Essa’s Mbithi would like to see how projects like CMU-Africa pan out before deciding whether branch campuses can address the scale of the challenge facing African higher education.

“I have always had the question in mind of what percentage of the population does [a branch campus] benefit, especially those coming from low-income backgrounds,” he says.

Another capacity-building measure that has risen to particular promise post-pandemic is online degrees. Previously, Mbithi says, it was difficult to convince employers to recognise such qualifications. But now that they have seen the skills that online graduates have, this teaching mode “can be a big potential pathway in the future”.

Izel Kipruto, Essa’s Kenya-based head of communications, is aware of mass course providers such as Coursera becoming very popular in Africa and she foresees them becoming invaluable to teach emerging technologies such as advances in artificial intelligence, which only a few local people are qualified to teach.

However, in other subjects, there may be major issues with courses that do not have content that is relevant to African students, and Lawson says that “without a background degree from a local university you find some issue of recognition”. His view is that online instruction only will mainly be useful in specific skills areas, such as coding.

Given that most African governments’ education ministries are focused on primary and secondary education, it is clear that much of the slack in higher education will have to be taken up by the private sector – and not just on course provision. According to Essah, “interesting” private alternatives to the public financing of students are also emerging, whereby investors pay for students’ higher education and find jobs for graduates in return for receiving some interest on their investment later.

But Mbithi says African governments must realise that it is foolish to “neglect” tertiary education even as they ramp up school spending. “The reality is that those that are transitioning from free primary and free secondary education have nowhere to go for higher education,” he points out.

Kuyok agrees that “funding is key”, but says that countries that are increasing their education spending, such as Rwanda and Botswana, “are increasingly doing well in terms of meeting the needs for students and provision of quality HE”.

But could such countries take up the slack not only nationally but also for the continent as a whole?

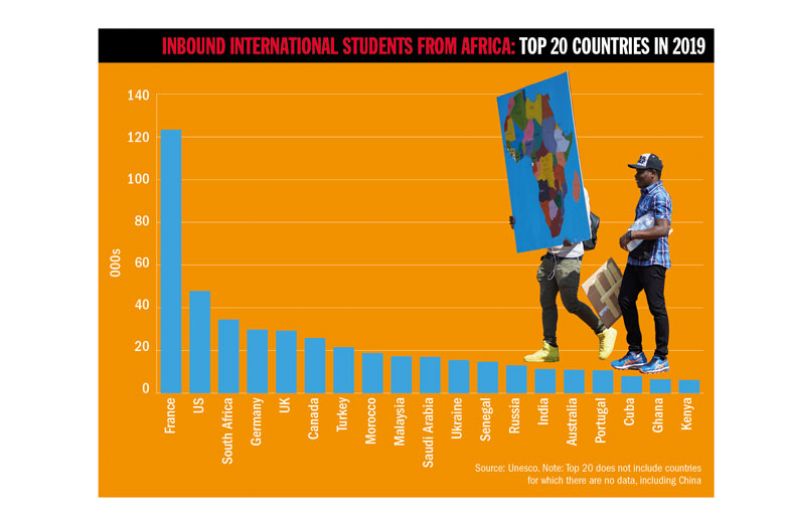

The latest Unesco data give some indication of the extent to which this is happening. Although France (with its links to francophone Africa) is way out in front for its volume of inbound international students from Africa, South Africa is third only to the US.

With its impressive group of world-class universities (it has five in the current Times Higher Education World University Rankings top 500), South Africa is always likely to be attractive to students who want to remain on the continent for their higher education. But, according to Mbithi, its lure has been eroded by its economic struggles and xenophobic attacks.

Still, Mbithi is hopeful that the future of higher education on the continent will lie in some kind of “pan-Africa” system whereby students study in several different countries. He points to attempts to create a common higher education area in East Africa and says such a model “can really work” given the different historical subject specialisms in different countries and regions.

Lawson says there is also evidence of increased student flows to northern and western Africa, with potential hubs like Egypt and Nigeria emerging for English speakers, and Morocco, Tunisia and Senegal for French speakers.

Anna Esaki-Smith, co-founder of internationalisation consultancy Education Rethink, believes the capacity of branch campuses in Africa could be boosted by some emerging intra-continental examples, such as Tanzania’s hosting of “a number of Egyptian university branch campuses”.

And Salmi points to other efforts to build stronger cross-border university networks, such as the World Bank-supported Africa Higher Education Centers of Excellence Project (ACE). Launched in 2014 with an initial focus on West and Central Africa, it “aims to promote regional specialisation among participating universities in areas that address specific common regional development challenges”. A second phase (ACE II) is now focused on 24 centres at host institutions in eastern and southern Africa.

Such partnerships are an “important strategy to support the capacity-building efforts of universities in the less endowed African countries”, Salmi says. However, he notes that South African universities are not participating in ACE II; he urges them to “resist the temptation of having research collaborations predominantly with universities in Europe and North America” and “leverage their advanced research and training capacity to…play the role of ‘big sister’ universities in thematic areas of priority for sub-Saharan African countries”.

Habib is even more forthright about his homeland, saying South Africa has the “same obligations that I demand of the [Global] North” and laments that its universities do not see intracontinental collaboration “as part of the regional developmental agenda…They do the same extractive relationship that I accuse Northern institutions of doing.”

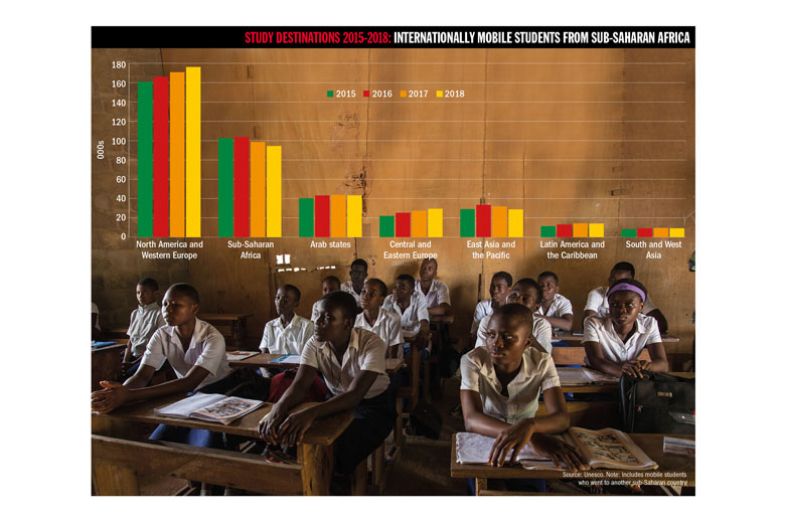

For all the talk of greater regionality, the pre-pandemic data suggest that the number of internationally mobile students staying in sub-Saharan Africa was falling, while the numbers going to North America and western Europe were on the rise. There was also noticeable pick-up in the numbers of sub-Saharan Africans going to central and eastern Europe, although numbers going to Ukraine and Russia are likely to have plummeted since the latter invaded the former in February.

Figures on student flows between Africa and China are scant in the Unesco data, but Chinese government data available from 2019 suggest that in the year previously there were 81,000 African students in the country, which would put it second only to France for inbound student flow.

Esaki-Smith says that before the pandemic, the Chinese government was offering a large number of scholarships to African students, which “was widely perceived as a strategic, soft power push into the continent. In addition, China has provided employment opportunities, such as those affiliated with the massive Belt and Road initiative, to African graduates of Chinese universities, which has also deepened interest in studying [there].”

Since no figures have been published since 2019, it is unclear how the internal and border restrictions imposed by China during the pandemic have disrupted this surge. Esaki-Smith is confident that while student flow was “severely impeded” by China’s zero-Covid strategy, it will pick up again when the situation stabilises. But Salmi is not so sure. He points out that “many African students have been stranded in China with little help, and sometimes exposed to racist behaviours, which is sadly ironic because Chinese students enrolled in European or North American universities have also faced similar negative reactions as a result of the pandemic”.

“Looking forward, Chinese universities have a lot to offer their African counterparts, but this requires a genuine spirit of mutual understanding and the willingness to forge long-term partnerships, [in which] the capacity-building needs of African universities…do not take second place behind the geopolitical interests of the Chinese government in Africa,” Salmi adds.

Kuyok says India should also be watched as an alternative for outbound African students disillusioned with China given its affordability and its English-speaking status. But experts suggest that Africans’ interest in Chinese options will not easily be diminished.

Many people in Africa “have a very positive look on China. Why? Because they can see something tangible that is happening on the ground,” says Mbithi. He adds that provided African governments are “good negotiators” with China, the Asian giant’s involvement in higher education could be “a game changer because China can deliver [higher education] infrastructure in a cheaper way [than the West], and also to a high standard”.

Essah agrees. “China gets Africa: they understand what our needs are,” she says. “It is like a barter system: we give this, we take that, we need your minerals, we need oil. Some people prefer that openness. With other parts of the Global North it is always hide and seek…There isn’t that transparency. So China will continue to have a role to play in economics and in higher education [in Africa] until we find our way” and become more self-sufficient.

China also benefits from having no colonial history on the continent. By contrast, Glasgow’s Haydon warns that if UK universities treat Africa’s youth explosion as just another resource to be exploited, it will be seen as a continuation of the colonial mindset.

“The dynamics of population growth and emerging economies suggest [the UK’s] current advantage in this sector, built on extractive approaches, is not sustainable,” he warns, adding that the “recent focus on recognising the UK’s colonial history” and how its universities benefited makes “the case for a broader reparative programme…particularly compelling”.

In the absence of a more sensitive approach, he says, UK universities will be “complicit in a myopic failure of global vision, leadership and responsibility”.

后记

Print headline: How can Africa’s thirst for higher education be met?