Here is an all too typical story of someone who experienced harassment within a university setting.

A mid-level female academic had complained to her faculty about long-term harassment and verbal aggression from a superior. But when she phoned the dean for an update on the case, the informal response was: “I want your boss to have some good years before his retirement; I’m not willing to give him a hard time for the rest of his career.”

“The fact that the dean voiced concern about his well-being rather than about mine hit particularly hard,” the woman told us. “I was given the feeling that I had complained too much. So they removed me from the situation, which resulted in my losing all my colleagues and courses and ending up with an insurmountable workload of new courses to teach, for a department that is not in my field of research. And at the same time, there are no consequences for the person who [harassed me].”

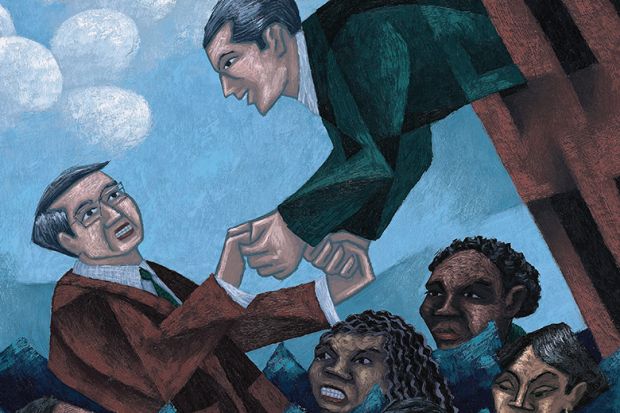

We heard many such stories when we were carrying out the research for a recent report, which is based on interviews with 26 self-selected academic staff at a university in the Netherlands. We looked at cases of power abuse, scientific sabotage, harassment and discrimination: what often happens when such cases are reported, and the impact on the individuals involved. Certain specific aspects of the academic environment – its intercultural and international nature, the heavy workload and the reliance on temporary contracts – make staff members especially vulnerable to abusive behaviour. But although power abuse can take shocking forms, many perpetrators seem unpunishable. The hierarchy that is integral to higher education creates a particularly safe environment for a certain kind of abuser: the successful professor who brings in large grants.

The academic staff we interviewed belong to different social classes and occupy every level of the university hierarchy, but a large majority are early or mid-career female non-Dutch scholars. They generally report that the perpetrators are their direct superiors: their line manager or head of department, who are almost invariably Dutch and male (men make up 74.6 per cent of professors in the Netherlands). The international nature of academic work is important here. Victims and bystanders are sometimes unaware of what constitutes unwanted behaviour or are told they do not sufficiently understand the local context. But they also sometimes have to deal with overt racism, as in the case of a professor who “would say really, really, offensive things about different groups of people in his classes” until the students eventually complained.

The individual stories we heard were heartbreaking, and since the publication of our report, we have received dozens more from colleagues who want to share their experiences. So it is high time to call out the abusers and shed light on the institutional processes that enable and protect them. Here we draw out some other important insights before going on to suggest what we need to do now to tackle abuse.

In our data, we saw individuals who have gone through harassment, power abuse, intimidation and discrimination for extended periods of time, often years. Micromanagement, verbal and even physical aggression are commonplace, as is the obstruction of scientific careers through the denial of opportunities and resources. Some respondents believed in promises of promotions based on merit, only to be disappointed by ever-changing performance criteria and evident instances of nepotism. One respondent described a supervisor who “keeps reminding us on an almost weekly basis that our promotion depends on his evaluation”. In cases of disagreement, he would add: “I will be negative in your performance and development interview – and your promotion depends on the interview.”

The long-term effects on the victims were severe. Besides a negative impact on careers and professional development, we found mental health problems, such as anxiety, panic attacks and even diagnoses of PTSD. These led, in turn, to a deterioration in physical health, as evidenced, for example, by sleeplessness and weight loss. One respondent described a sense of anxiety she was unable to control: “For three days in a row, or even longer, I was feeling...extremely anxious, and that did not let me sleep or eat and consumed a lot of my energy, and this is definitely not healthy. The feeling that 70 per cent of myself is already dead, and I have just 30 per cent of myself that has to do all the work: it’s exhausting.”

Almost all our respondents felt helpless, marginalised, unsafe and silenced during the process of reporting incidents of power abuse, harassment or discrimination. Many were confronted with denial or encouraged to self-silence. Some were explicitly advised to drop the matter for the sake of their careers. Often, the needs of known harassers were prioritised over the safety of their victims.

What this meant, according to one respondent, was that “many supervisors leave a trail of destruction behind them. They [management and HR] run around and quickly put out fires, but not thoroughly...Everything continues to smoulder, and the fire could start again at any time. They just want to cover it up.”

In cases where our interviewees refused to self-silence, they invariably experienced some form of retaliation. This could include delegitimisation of their experiences, such as being labelled as “overly sensitive”, “lacking a sense of humour” or “not familiar with the organisation”. Many found their complaints of harassment or abuse reframed as “conflicts” or were themselves labelled as troublemakers. This also meant that they were forced to get “fixed”, for instance through coaching or mediation. Not surprisingly, these measures caused them immense distress. Particularly retraumatising were the forced mediation sessions with perpetrators, who would typically continue with their abuse, but now protected by confidentiality clauses.

“Because they couldn’t touch my research performance,” one respondent told us, “they started a smear campaign [and used] my students to turn against me. They were taking revenge in any possible way. What they do is very inhumane. First, they try to break your self-confidence. If you don’t break, they start lying. They blocked my grants, they isolated me from my colleagues, they deleted my employee page.”

Others experienced equally tangible forms of punishment, such as having teaching responsibilities or PhD students taken away from them or receiving negative performance evaluations. Others reported being forced into non-disclosure agreements and leaving the university “voluntarily”. In fact, roughly half of our interviewees had left the university in question because of their experiences and the backlash they had to endure for reporting what had happened to them.

Not surprisingly, among survivors and bystanders, a culture of fear and hopelessness develops, leaving people within the university disillusioned. As a result, apart from the catastrophic consequences for the individuals who are targets of harassment, the wider institution is negatively affected, too. Productivity decreases and employees become increasingly detached.

Despite all this, the existence of harassment is very much an open secret. When one interviewee talked to her dean about the behaviour of her line manager, he merely replied: “I know. I went through the same when I was assistant professor with my own line manager.” When she followed up by asking why he didn’t do anything to change things now that he had more power, he simply said: “Because this is the system. This is how it works.”

It is important to stress that the patterns of harassment and abuse, exacerbated by protection of perpetrators, that we have found are not just a local Dutch problem. Colleagues from around the world have contacted us to tell us that they recognise them. So how can we move on from what we have learned towards finding solutions? We want to end with three central insights and draw out some suggestions from them.

First, the pervasive ineffectiveness of anti-harassment and non-discrimination policies results from the fact that those who are mandated with implementing them are often the very people who will lose their power and privilege if they do so. As Sara Ahmed noted in her 2019 book, What’s the Use?: On the Uses of Use, the system is working by stopping those who are trying to transform the system.

The implementation of zero-tolerance policies and effective complaint procedures therefore requires the active involvement of underrepresented groups, while ensuring their safety if they speak out. The monitoring of workplace safety should be done by external auditors, and sanctions should be imposed on universities that repeatedly violate their duty of care – as determined by the targets of abuse. There are places where this is happening. For instance, the National Institutes of Health, the largest funder of research in the US, has already removed over 70 heads of laboratories from grants after receiving complaints of (sexual) harassment and racism that the agency considered well founded. Importantly, because universities need grant money, such measures incentivise the enforcement of anti-harassment and non-discrimination policies. Europe should follow the NIH’s lead in protecting the targets of harassment rather than the harassers.

Second, the intersectional nature of inequality burdens those most vulnerable with calling attention to the harassment and abuse they are exposed to. We believe that awareness training should be mandatory, so that potential targets of abuse are empowered to recognise what is happening to them and can seek support early on. Increasingly, collectives of academics do amazing work in this regard. Examples are the 1752 Group in the UK, a research and lobbying organisation working to end sexual misconduct in higher education, and the Parity Movement in the US, which fights academic discrimination, violence and bullying. Other associations oppose the casualisation of academic staff, which is important since academics in precarious employment are more dependent on their managers and so suffer more harassment and abuse. A case in point is 0.7 in the Netherlands, a recently founded advocacy group to combat the structural use of temporary contracts for academic staff.

Large funding organisations could also monitor whether the money they hand out to universities to recruit members of underrepresented cohorts is serving its purpose. About a third of our interviewees were hired through a gender equality scheme funded by the European Commission. Those targeted by such programmes often belong to particularly vulnerable groups, such as foreign women. Large funders may inadvertently contribute to their plight if they fail to follow up on the outcomes of such schemes.

Finally, the damage caused by universities that fail to implement effective anti-harassment and non-discrimination policies, as well as effective complaints procedures, is significant. Some of our interviewees are still in treatment by clinical psychologists years after having left a university that allowed such traumas to be inflicted on them.

This points to universities’ unconstitutional discrimination and neglect of their duty of care. The legal frameworks that are in place to protect employees from bullying should therefore be put to the test. Legal scholars have argued that bullying in higher education should be considered a violation of human rights because it denies the victims’ dignity.

The higher education sector is in dire need of reform, as has been acknowledged by many stakeholders. What we now need to recognise is that mandating those whose power and privilege are threatened by such reforms to oversee them simply reproduces an unsustainable status quo while causing unacceptable damage to academic staff.

Nanna Haug Hilton and Susanne Täuber are associate professors at the University of Groningen.

后记

Print headline: A sanctuary for abuse?