One of the central challenges faced by Western universities that now have a heavy reliance on Chinese students has been highlighted in a new set of data.

The Patterns and Trends report, from Universities UK, contains a chapter on demographic trends that shows how the Chinese youth population is projected to shrink by a quarter from 2015 to 2025.

In the UK, US and many other Western nations, China has become the dominant source of international students over the past years: according to the report, during the 10 years between 2006-07 and 2015-16, the number of students coming from China to study in the UK almost doubled. Figures released earlier this year from the Home Office on the issuing of visas to Chinese students also illustrated the trend.

The demographic projections for China will therefore make challenging reading for universities that have come to rely on fees paid by international students to boost their income.

However, other countries that have also been a key source of international students – such as India – are not projected to see such a fall in the population of 18 to 24-year-olds over the next few years. In fact, India is projected to have almost the same number of 18 to 24-year-olds in 2025 as China did in 2010.

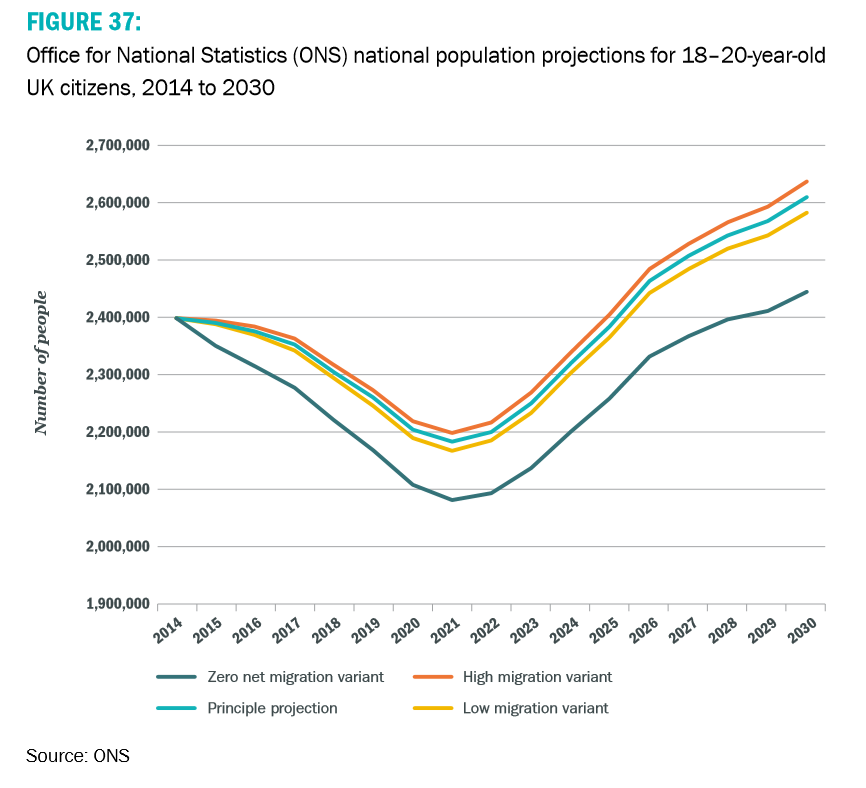

The report also highlights how the UK’s domestic youth population is projected to change over the next 10 to 15 years. Currently, the number of 18 to 20-year-olds is on a downward trend that has long been anticipated.

University applications from the age group have continued to grow in recent years, thanks to the increasing rate at which people are applying. But, the report warns, “further improvement in the young entry rate will be needed to maintain student numbers at current levels” as the demographic dip continues.

The good news (or possibly a challenge) for the UK’s university system is that after 2021 the youth population is projected to climb again quickly, reflecting a baby boom over the past 10 years that has been testing schools capacity in the country.

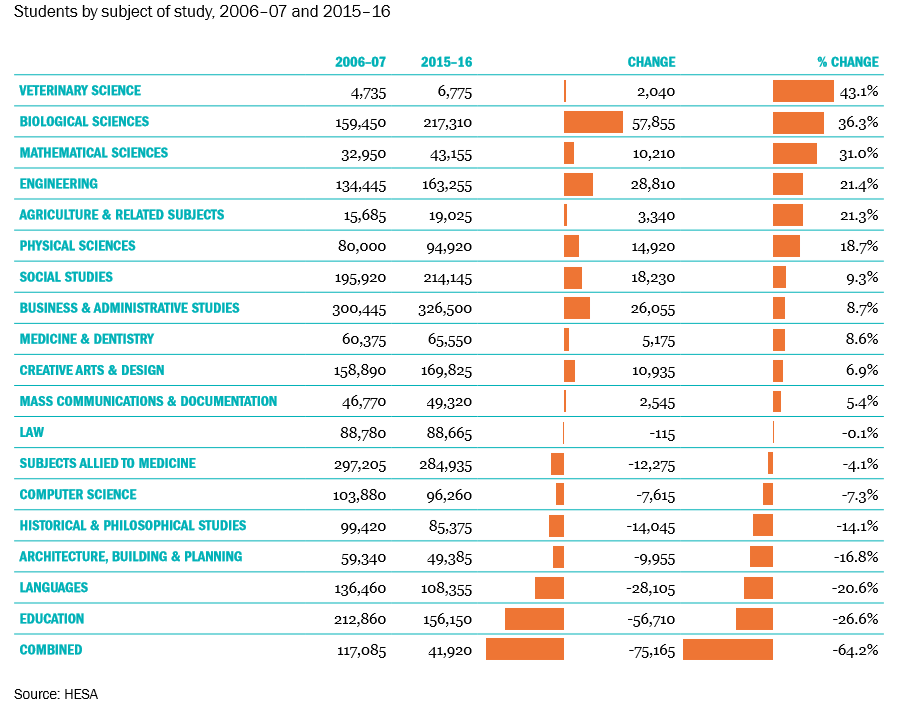

Elsewhere, Patterns and Trends contains some stark figures showing how the popularity of different subjects at UK universities has changed over the 10 years to the 2015-16 academic year.

The trend towards more students studying science, technology, engineering and maths (STEM) courses is clear, while the popularity of some arts and humanities subjects such as languages and historical/philosophical studies has plummeted.

However, the report points out that for some of the subjects that have seen growth over the period, a large share of students are from overseas, “most notably for engineering (13.1 per cent are non-UK), business and administration (31.5 per cent) and social studies (9 per cent)”.

“These subjects therefore remain vulnerable to any future volatility in the international student market, or increased immigration restrictions,” the report warns.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view