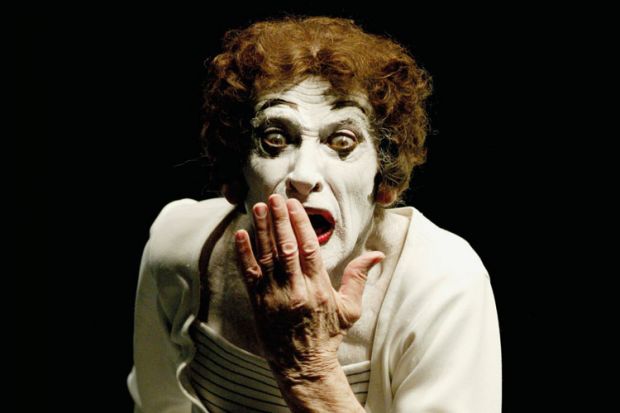

Could mime hold the key to improving university teaching?

The idea may seem fanciful, even deranged, to many academics who might wonder what a silent theatre form can add to tutorials, seminars and lectures, where the free flow of words (the antithesis of mime) is often the main aim.

But the physical expressiveness of mime – using actions and gestures to articulate ideas – can hugely enrich lessons, says Gilberto Scaramuzzo, director of the Laboratory of Pedagogy and Expression at Roma Tre University.

At Scaramuzzo’s centre – known as MimesisLab – educators, artists and professional performers learn how to use the art of mime for teaching purposes.

“It’s not about learning a collection of techniques,” explains Scaramuzzo, who trained as a mime artist and actor before entering academia, where he focuses on the philosophy of education.

“Mime is about going deep into yourself – you have to go to a place where you think [about] movement, actions and the human dynamic,” he says.

So how does that apply to higher education? Scaramuzzo suggests that educators must seek to connect with their subject on a more visceral level and then find words through movement. Students should, in turn, also be encouraged to use mime in lessons to confirm their understanding of a subject.

“If we want to speak [on a topic], we must learn to become [the topic] – and to become we have to really try to connect with the words we are saying,” he explains.

Scaramuzzo’s theories on teaching are heavily influenced by the Italian theatre director and educationalist Orazio Costa, whose mime-influenced method asked actors to “become” the words they expressed.

He also traces the use of mimesis in education back to Plato and Aristotle, who, he says, understood its huge value.

“Aristotle said humans are the most mimetic animals in the world – we have this unique capability in our brains to perceive likeness,” he explains. “The creation of likeness was central to his teaching method – mimesis helps to bring learning alive.”

The process of mimesis might feel rather forced for many educators, whose prime focus may be honing their lecturing skills or facilitating class discussions. But the physicality of mime comes naturally to most people, Scaramuzzo contends.

“We don’t teach babies using only words – we teach with facial expressions, movement, actions.”

Mime does not lend itself only to the more artistic or creative disciplines, such as English literature, theatre or dance, but can be used more widely in scientific subjects, he says.

For instance, a talk on volcanoes or the water cycle could be enhanced if a lecturer asks their students to embody through movement the words they have heard.

“Instead of remaining passive and listening, students should be invited by the teacher to explore the subjects using their mimetic capability because in acting there is understanding,” he explains.

For instance, those learning a foreign language might think about the extent to which physical gestures are part of the language and culture they are seeking to master.

“It can definitely change the dynamic between students and teachers,” adds Scaramuzzo, who directs a master's course in the pedagogy of expression (Pedagogia dell’Espressione) at Roma Tre.

Those master’s students have been encouraged to use mime to teach all types of students, from schoolchildren and undergraduates to recently arrived migrants and prison inmates.

Elements of mime can be used to gain the attention of and properly engage students in lessons, says Scaramuzzo, who has just completed a visiting fellowship at the University of Cambridge’s Faculty of Education.

In Scaramuzzo’s case, his method of attracting and holding the attention of a group was learned as a street mime artist in Rome and Berlin.

“You cannot get a better teacher than the street,” he says. “No one is there for you, so you need to find a way to get attention – you have to connect with everyone around you while you perform or you lose them.”

But the content of his act was only part of the equation, he realised. “If you want to receive something from an audience, you have to give something to them – not just technique, but passion, honesty and part of yourself,” he says. “That can only come from a place of truth inside you, and the same is true for teaching.”

后记

Print headline: The silent treatment: use the art of mime to enhance learning