In many ways a sequel to his 2004 book Love Saves the Day: A History of American Dance Music Culture, 1970-1979, which covered New York’s underground music clubs during the 1970s, Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor offers, across 500-plus pages, highly detailed insights into the melting pot of New York’s creative nightlife during the first four years of the 1980s. The city’s night-time cauldron of experimental sounds, sights and lifestyles attracted artists, musicians, social outcasts and general party animals from afar, adding fuel to a developing community of what may well be regarded as pioneering cultural entrepreneurs.

Around 1980, as the US economy moved towards yet another recession and its largest city struggled with public debt and rising crime, the austere economic and political context would not seem, on the face of it, to have called for a party. But against the odds, as Lawrence documents, hedonism-in-hard-times was being celebrated in the Big Apple to the full. The cost of living in the city was still relatively low and the will to innovate prolifically high.

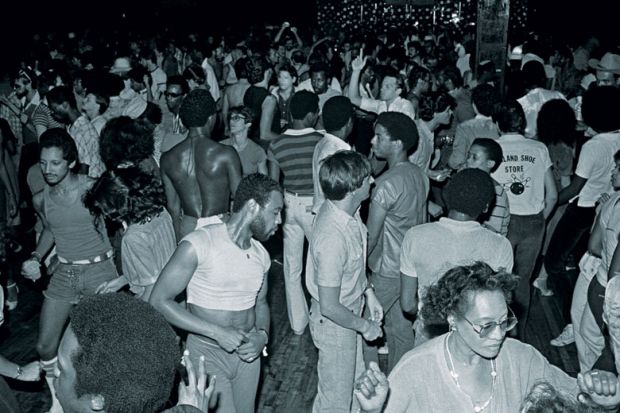

The energy that radiated from New York during those years was inspiring. To this day, I remember dancing among a black and Latino gay crowd in the large rectangular concrete space of Paradise Garage in 1983, amazed at how the sub-bass moved the hairs on my arm, and how the instrumentation was crystal clear in the higher frequency range, and yet I was able to have a conversation without raising my voice. In that same year, I paid several visits to Danceteria, where multiple floors offered simultaneous events on a DJ-driven dance floor where Mark Kamins played eclectic sets, a music stage showcased British bands booked by Ruth Polsky, and a mostly white post-punk crowd walked up and down the dark, narrow staircase to hang out on the hot summer roof many floors higher.

Then there was the Roxy, a huge ice rink converted on Fridays to accommodate an electro night, with scaffolding in the middle of the floor for the DJs, who boosted their music selections with synthesisers and the characteristic booming kick drum sound of the Roland TR-808 drum machine. One night I recall seeing African American dance groups compete with each other by creating slowly rotating human towers, spinning as one strongman held the weight, while producer Arthur Baker listened to how his new mixes worked on the floor. On that same evening I also experienced Funhouse, where Baker’s friend, the DJ-producer Jellybean Benitez, manned the decks in the open mouth of a laughing clown’s face, entertaining a predominantly Latino crowd, as dancers poured chalk on the floor of what looked like a boxing ring to smooth their dance moves. And on a Sunday morning, we ended up at David Mancuso’s Loft, where a precision hi-fi sound system managed to articulate every part of a recording at a significantly lower volume than the clubs mentioned above.

Similar experiences inspired people elsewhere in the city to set up their own clubs and start producing genre-defying music, mixing punk, funk, jazz and electro into what eventually became new styles. It was the same kind of fusion that could be seen in the development of artists such as New Order, who had in effect evolved from the proto-goth band Joy Division into a guitar-synth indie pop outfit, and who worked with New York luminary Arthur Baker on several electro mixes. They were inspired to start a nightclub in 1982 in Manchester, The Haçienda, FAC 51, which never quite managed to offer an equivalent sound quality but nevertheless pursued a music policy as eclectic, and party concepts as mind-boggling, as New York offered at the same time.

This fertile, promiscuous mix of ideas and activities that Lawrence captures here had been heralded in the previous decade by the mix and match aesthetic of early disco and hip hop pioneers, by conceptual art and Situationist-inspired punk practices, as well as by the liberating libidinal politics of New York’s underground night scene. Although disco had lived through its mainstream peak by the turn of the decade, its legacy lived on. Initially defying definition and thereby developing under the radar away from mainstream media interest and major record labels, during the early 1980s these scenes, genres and creative approaches met and melded during the creative chaos of night-time culture, when the world can be approached in an alternative way, and accepted daytime values can be turned upside down. As one of Lawrence’s interviewees observes, during those years it felt like it was Halloween every night.

The dark flip side of this convergent energy came with the arrival of Aids, which was able to move as fast among an intermingling crowd of queer revellers as a new party concept, sound mix or performance approach. For many participants, the dance floor literally became a way of life and death. In addition, the cultural capital generated in these scenes and neighbourhoods was converted to economic capital within just a few short years, as affluent consumers were attracted to the range of nightlife venues. Real estate values inflated, and eventually pushed out the very people and parties that made downtown and midtown areas attractive in the first place. As Lawrence puts it, the city’s shift to post-industrialism offered new cultural opportunities, yet the increasingly neoliberal aspects of its financial organisation, along with gentrification and social regulation, ultimately unmade it. By 1984, the almost indefinable complexity of this underground (or “subterranean”, to use Lawrence’s terminology) dance realm began to crystallise and separate out once more into distinguishable and marketable music genres, from no wave to post-punk, from garage to house, and from hip hop culture and rap to electro – mostly, it seems, defined by the British music industry and (subcultural) press. And so the lively exuberance of those dance floors died, eventually, quite literally.

Lawrence catalogues the ephemeral cultural experience of these years with as much precision as the collective memory of the interviewees and archives of contemporary reviews, articles and numerous insightful DJ playlists can afford. The main body of the book is organised in a chronological, yet thematic, manner, around a series of portraits of and interviews with individuals who significantly influenced the main dance-floor events and parties. The advantage of this approach is that the memory of events is kept very much alive through the witness accounts of its survivors. The downside is that, despite the socio-economic and conceptual contextualisation of events, the tendency is towards heroes and zero-moments in what is a complex set of cultural processes put in motion by communities of people that defy definition. After all, a club owner, party promoter or DJ is nothing without their crowds of willing participants who together contribute as much as any named person. In terms of presentation, it is not always clear what the significance is of certain named individuals until a chapter is well on its way, and the reader can sometimes become lost in minutiae, such as an event at Club 57 that attracted fewer people than a small house party, or the initial selection and placing of specific speakers in the Paradise Garage. The presentation of such a huge wealth of material allows for an ethical approach, in which facts are checked and compared in both documentation and living memory.

The result is a treasure trove for anyone interested in the melting pot that produced not only vibrant music and party concepts that still echo within current global night-time cultures but that also (as witnessed in Semiotext(e) and Autonomedia publications) resonate in practice with the anarchic ethos of post-structuralist radical philosophy. During the early 1980s, New York’s night culture offered a glimpse of the possibility of a different reality. As Ivan Chtcheglov’s 1953 Situationist text “Formulary for a New Urbanism” states, “And you, forgotten, your memories ravaged by all the consternations of two hemispheres…without music and without geography, no longer setting out for the hacienda where the roots think of the child and where the wine is finished off with fables from an old almanac. That’s all over. You’ll never see the hacienda. It doesn’t exist. The hacienda must be built.”

Hillegonda Rietveld is professor of sonic culture, London South Bank University.

Life and Death on the New York Dance Floor, 1980-1983

By Tim Lawrence

Duke University Press, 600pp, £83.00 and £22.99

ISBN 9780822361862 and 362029

Published 30 September 2016

The author

Tim Lawrence, teenaged David Bowie devotee turned professor of cultural studies at the University of East London, was an undergraduate in Manchester in the late 1980s. It was there that he caught a glimpse of a legendary dance club at its height; consolation, perhaps, for the fact that by the time he went to New York to study with Edward Said for his doctorate, the clubs and parties of which he writes here were history.

He recalls: “The Haçienda had already been open for a few years, but the summer of 1988 was the year that it exploded and I walked into it by mistake. I had the time of my life but didn’t know much about the culture at that point...I was young and quite naive.

“I don’t regret experiencing the Haçienda only fleetingly because in retrospect there was something unsatisfactory and unsustainable about that culture. House music was transformational at the time but at some point it started to feed into a culture of sameness,” he observes.

“But I certainly wish I had lived in New York City during its 1970s and early 1980s heyday. Parties such as the Loft, the Gallery, the Paradise Garage, Better Days, the Mudd Club, Club 57, Danceteria and Pyramid have never been surpassed in terms of the way they drew together mixed crowds and kaleidoscopic sounds. The city brimmed with potential.”

Of the many interviewees for this book, Lawrence says that “Steve Mass (the Mudd Club) was the most interesting, Afrika Bambaataa (Negril, the Roxy) the most surprising, Mark Kamins (Danceteria) the most touching, and Anita Sarko (the Mudd Club) the most valuable. Mark and Anita died while I was still writing the book and I think about them a great deal.”

What gives Lawrence hope?

“The dance floor, the revival of democratic socialism, shadow yoga, my family and friends, and, since I moved to a house a year ago, a spot of gardening.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: Every night was Saturday night